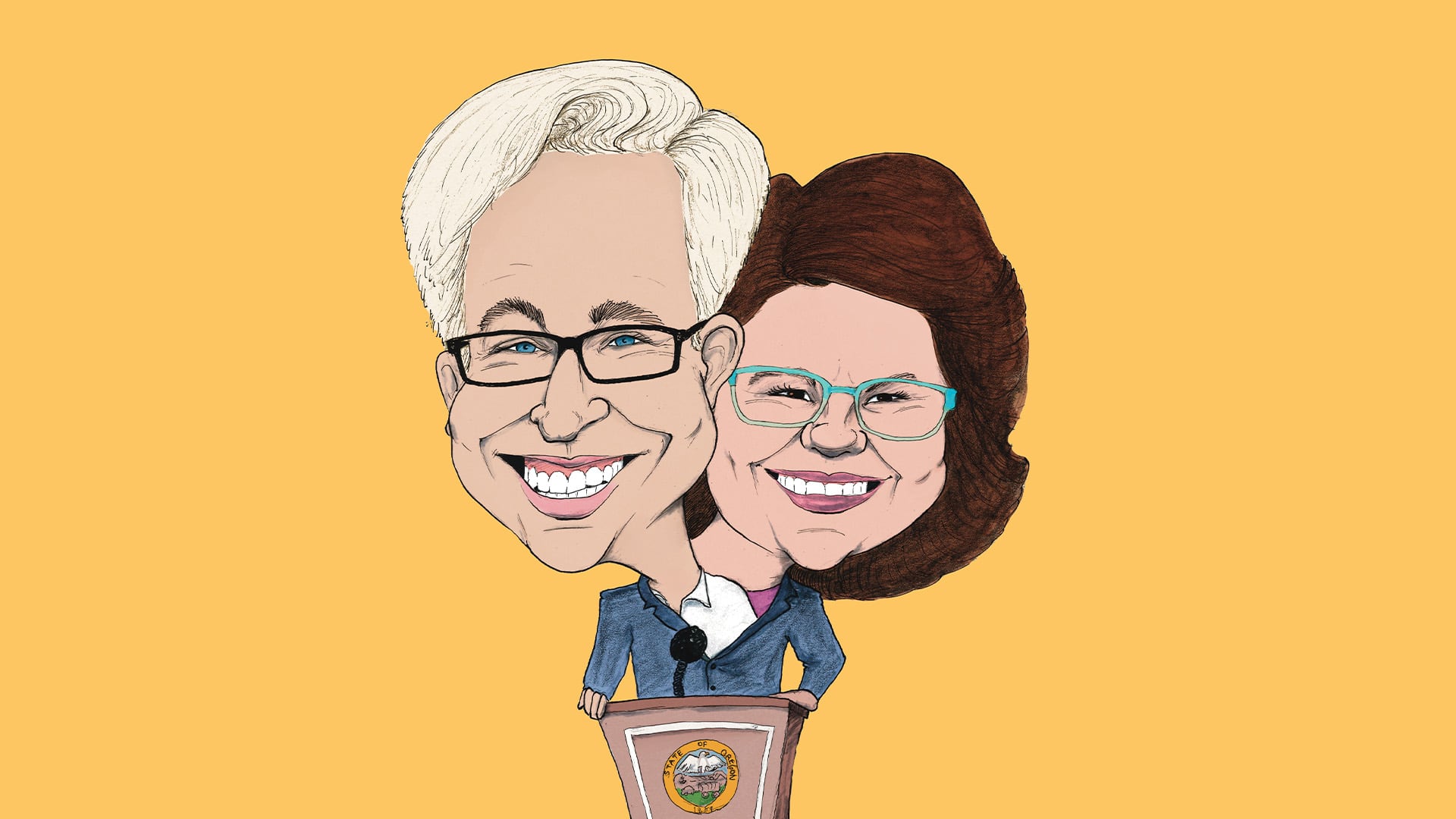

Aimee Kotek Wilson stands in the middle of the biggest firestorm of her wife’s young governorship.

When Tina Kotek ran for governor in 2022, she’d already been speaker of the Oregon House for nearly a decade, the longest tenure in the state’s history. Decisive, focused and transactional to the point of ruthlessness, Kotek was a known commodity.

Her partner of nearly 20 years, not so much.

That all changed March 22, when the governor’s office ignited a white-hot story with a Friday press release (dropping damaging information when people are focused on the weekend is a time-honored political tradition).

The release said Kotek’s chief of staff, Andrea Cooper, was leaving. It soon became evident that Kotek had actually fired Cooper. In addition, two of the governor’s other top aides, special adviser Abby Tibbs and deputy chief of staff Lindsey O’Brien, were also departing. Three-quarters of Kotek’s executive team, gone.

An exodus from the highest levels within the Oregon governor’s office this early in a first term is historic. And those who left have not yet been replaced.

After interviewing more than two dozen Salem insiders, reviewing thousands of documents that Kotek’s office released under Oregon’s public records law, and examining Kotek Wilson’s calendar, an inescapable conclusion emerges: The departure of key staff leads back to one person—the first lady.

Kotek Wilson, 47, is her wife’s closest adviser and, the staff exodus shows, her top priority. In many ways, she is Oregon’s co-governor, although she rejects that premise. “That is ludicrous,” she says. “There is only one governor in Oregon and it’s Tina Kotek.” (Kotek Wilson declined interview requests for this story, choosing instead to answer questions in writing.)

Records show that Kotek’s most senior aides—Cooper, Tibbs and O’Brien—asked the governor repeatedly to allow staff members to do their jobs without interference from Kotek Wilson, a former social worker who inserted herself into policy and personnel matters.

It’s also clear that when the governor’s top staffers repeatedly insisted on greater structure and transparency around her spouse’s role, the governor pointed them to the door.

The departure of three loyal, highly regarded senior staff stunned many in Oregon politics. Former Secretary of State Jeanne Atkins, a Democrat who has worked with three of the women who left, echoed the assessment of many.

“We are talking about three of the strongest staff members out there,” Atkins says. “Good people are really hard to find, and the relationships they had are hard to rebuild.”

“It’s really messy,” says Felisa Hagins, political director of Service Employees International Union Local 49, who has known the governor and first lady for 20 years. “I think Tina underestimated the ripple effect.”

In the following weeks, two more senior staff members would also walk (see “The Five Who Left,” page 17).

Interviews and public records reveal a governor who has few close friends or advisers and is highly dependent on her spouse, whom people describe as both warm and erratic, the polar opposite of Kotek. The governor grinds toward her goals with an unyielding determination, except when her wife is involved. Their relationship would be irrelevant—if not for the long shadow Kotek Wilson has cast over Kotek’s administration.

“This governor has one blind spot,” a longtime associate says. “It’s Aimee.”

On Sept. 15, Kotek and a handful of ranchers convened at one of Pendleton’s architectural jewels, the Raley House, a restored Queen Anne-style home built in 1876.

The purpose of the meeting: to discuss using Eastern Oregon rangelands to sequester carbon and generate lucrative energy credits.

At Kotek’s side at the head of the table, a smiley, small (5-foot-1, according to her driver’s license) woman with big thoughts on the topic: Aimee Kotek Wilson.

Without introduction, Kotek Wilson dived in, offering her ideas and asking questions. To one participant, her involvement seemed strange. “It’s not really her issue,” the person says, “but she talked a lot.”

Kotek says the meeting was routine. “It was an informal discussion about carbon sequestration,” she says. “All participants engaged in the conversation, including the first lady.”

Energy policy is indeed outside Kotek Wilson’s wheelhouse—she holds a master’s degree in social work from Portland State University—but records reveal she regularly joined policy meetings on a variety of matters.

She met often with the chief of Providence Health & Services’ behavioral health division; with Deloitte, the consulting firm helping the state rethink behavioral health; and with a judge, corrections officials, employees at the state’s psychiatric hospital, and industry leaders, such as Becky Hultberg, director of the Hospital Association of Oregon.

Sometimes, Gov. Kotek’s aides expressed surprise at her participation.

One example: in January, Kotek Wilson decided she wanted to join the governor’s scheduled meeting with Oregon Labor Commissioner Christina Stephenson.

“I just got a call from Commissioner Stephenson’s chief of staff about her meeting with the governor tomorrow,” Kotek’s then deputy chief of staff, Lindsey O’Brien, wrote in a Jan. 30 email. “She noticed the first lady had been added to the calendar and asked me if that was correct and if we wanted to shift the agenda at all.…I hadn’t heard anything about this change.”

In 2004, when Tina Kotek first ran for a seat in the Oregon House representing Northeast Portland, her campaign manager was a young political operative then named Amy Jo Wilson.

The two women hailed from different backgrounds: Kotek grew up Catholic in Pennsylvania, while Wilson grew up with a Catholic mother and Mormon father in Arizona. But they’d both arrived in Portland after college to start fresh in a city that welcomed lesbians and cared little for religious affiliation.

Kotek lost that primary—Chip Shields beat her 55% to 45%—but she’d found a new partner (one whom she paid $5,233.31 to manage her campaign).

When Kotek entered the May 2004 primary, she had a different partner, Judy Donald. But after she lost to Shields, records show Kotek sold her share in their Northeast Portland home to Donald and, within a year, bought a home in Kenton with Wilson.

Wilson was building her own political résumé. She first came to Oregon in 1999 as a college intern helping farmworkers in Woodburn get housing. “The internship was my first exposure to community organizing,” she says, “and set me on a path to fight for others in Oregon.” After graduating from Antioch College in Ohio, she moved to Portland in 2000 and became a community organizer for Oregon Action. She moved on from there to a variety of political jobs, including working for the state’s largest labor organization, Service Employees International Union Local 503.

“She did lobbying and organizing and membership engagement for us,” says Arthur Towers, then the political director of SEIU Local 503. “She did a good job.”

In 2007, Democrats took over the Oregon House, giving them control of both chambers of the Legislature for the first time since 1989.

Kotek, then a first-term lawmaker who’d won an open House seat in North Portland, carried two landmark gay rights bills across the finish line.

When the bills passed the House, Kotek invited Wilson, who’d lobbied the bills for SEIU, out onto the House floor. Kotek kissed her partner on the cheek to celebrate.

Wilson’s presence on the House floor irked House Minority Leader Wayne Scott (R-Canby) and a business lobbyist. Both cited a rules that barred lobbyists from the House floor during official proceedings.

The image of the couple on the House floor cemented a political and romantic partnership and also demonstrated that even as a rookie, Kotek put her relationship with Wilson ahead of established norms.

“Early on, Tina was willing to be very public about her love for Aimee and the strength of their personal relationship,” says Mary Botkin, a former union lobbyist for the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees who worked on the civil rights bills.

Botkin says she’s not surprised Kotek Wilson wants a role in her wife’s administration: “Anybody who’s ever worked with Aimee knows she’s never going to be a wallflower and sit in the corner and be quiet.”

In 2008, Wilson managed her first statewide campaign, helping then-Senate Majority Leader Kate Brown (D-Portland) get elected secretary of state. After Brown won, Wilson joined Brown’s staff as a lobbyist in 2009. In 2010, she landed at SEIU Local 49 as interim political director.

After that, Wilson returned to the Legislature, serving in 2011 as legislative director to Democratic Co-Speaker Arnie Roblan (D-Coos Bay). Friends and work colleagues almost universally use the same words to describe Kotek Wilson: “Bubbly, with high energy and lots of ideas,” a legislative colleague says.

“She’s like the lady who lives next door and doesn’t have her own kids but loves yours,” another former colleague says. “She’s very relationship oriented, in contrast to Tina. She’s kind of a cut-up and can be really funny.”

Kotek is generally unconcerned with her appearance. Kotek Wilson, the opposite. For years, the couple commuted to Salem in Kotek’s 2004 Honda Civic, part of a daily legislative convoy from Portland.

“I would always see her on I-5 with curlers in her hair,” a former legislative staffer says. “She really likes hair and clothes and makeup.” Kotek Wilson says that’s accurate: “I still do curlers in the car.”

In Salem, Wilson ran with a hard-partying crowd. A karaoke fan, she loved finding a partner to sing the Indigo Girls’ “Closer to Fine.”

But her drinking became an issue. Several people point to a 2011 party at the end of the legislative session—the sine die party—at the Salem Convention Center. Wilson drank herself into a public mess, and Kotek struggled gamely to calm her.

A few months later—on Aug. 26, 2011—a Portland police officer was summoned to the intersection of North Lombard Street and Wabash Avenue (about five blocks south of Kotek and Wilson’s house) to deal with a drunken Wilson. The officer found her propped against a building.

“Her words were so slurred that I could barely understand her,” he wrote in his report, which WW obtained under a public records request. Wilson told him she wanted to walk home. “I believed she was a danger to herself, and if she walked home, she could be struck by traffic” he wrote. Instead, the officer cuffed Wilson and drove her to a downtown sobering center.

As Tina Kotek consolidated power in ensuing years, former lawmakers and legislative staff say there was only one thing that could break her machinelike pursuit of her agenda—Wilson’s erratic behavior.

The first lady has since spoken openly about her struggles. “I am a person who lives with mental illness,” she said March 26. More recently, she expanded on that. “Nearly a decade ago, I got sober,” Kotek Wilson says. “Getting sober allowed me to accomplish many things. My takeaway is that I haven’t given up on myself, and I won’t give up on Oregonians.”

In 2013, Kotek served her first session as House speaker. Around that time, Wilson left politics to work for Health Republic, a Lake Oswego health insurance provider, in community engagement.

Former colleagues said the job didn’t go well. “She’d come in and just start talking about things that had nothing to do with her job description,” one of them says. “She never did the organizing she was hired to do.”

In 2014, Wilson’s job at Health Republic ended. She did not return to the office. The company offered to send personal effects from her desk to her home. She refused, insisting Kotek would drive to Lake Oswego to fetch them.

Kotek herself showed up at Health Republic’s office after hours and grimly fetched Wilson’s belongings “It seemed to be about Tina needing to show support for Aimee—and Aimee’s need to prevail,” a former Health Republic colleague says. “We all thought it was ridiculous.”

Kotek and Wilson married Dec. 31, 2016, at what is now Polaris Hall in North Portland, in a ceremony presided over by Gov. Kate Brown. The first lady then changed her name to Aimee Kotek Wilson on Aug. 23, 2021, as Kotek prepared to run for governor.

Kotek and her wife’s social circle is small. In Salem, they often socialize with Maya Crawford Peacock, long a close friend of Kotek Wilson’s and now the governor’s appointments secretary.

Before moving to Salem, one of their regular pastimes in Portland was going to the J & M Cafe in inner Southeast Portland for brunch, then attending matinees of superhero movies with former Portland City Commissioner Steve Novick and his now ex-wife Rachel and James Barta, a former legislative staffer, and his wife.

Rachel Novick, now a professor at the University of New Haven, says she and Kotek Wilson bonded over having partners who were elected officials.

“As a political spouse, there’s just this strange set of expectations placed on you,” Novick says. “It’s a very tough spot.”

Novick adds that she found Kotek Wilson to be curious, thoughtful, intensely loyal and adept at perceiving connections between politics and policy. In 2015, Kotek Wilson entered the master’s program at PSU, working afterward as a case manager and counselor at Cascadia Behavioral Healthcare. Novick says Kotek Wilson has a lot to offer the state.

“I would be disappointed in both of them if they didn’t find a way to put Aimee’s experience and skills to work,” Novick says. “It would be an outrageous misuse of her ability if she were just going to ribbon-cuttings and ceremonial events.”

That’s a sentiment others share. Jason Renaud, director of the Mental Health Association of Oregon, says previous governors only paid lip service to improving Oregon’s dreadful behavioral health services. He says Kotek Wilson’s struggles could change that.

“‘Lived experience’ creates a unique and well-tested lens through which to understand mental illness and addiction, to reshape both public health policy and practice to be both cost efficient and clinically effective,” Renaud says.

Indeed, records show that Kotek determined that her wife would play a central role in Oregon’s attempts to improve its behavioral health services.

The governor included her wife in a behavioral health “pod,” combining governor’s staff and agency officials, and allowed her to interview Kotek’s top candidate for behavioral health adviser and then hold a weekly call with that adviser, Juliana Wallace, after she was hired.

Records also show that Kotek’s solicitousness toward her wife extended to topics large and small.

In emails, the governor regularly used the term “we” to indicate she was communicating a shared vision. Kotek also homed in on minor details that concerned her wife, bristling at the photos the National Governors Association used. “Please send NGA my official photo and the official photo of the FL [first lady],” Kotek wrote in a Feb. 20 email. “They need to stop using any photo they feel like.”

One telling example of Kotek’s focus on Kotek Wilson’s happiness: Emails show that on March 8 Kotek took the time to line-edit a draft manual for the proposed office of first lady. Among her concerns, according to her edits and email: whether Kotek Wilson, who has failed to sign any of the workplace disclosure forms or conflict-of-interest forms that other staffers sign, would get sufficient workplace protections, such as workers’ compensation coverage.

At a May 1 press conference at the Oregon State Library, Kotek rejected the premise that her most senior staff left her office because of their concerns about the disruptive nature of Kotek Wilson’s engagement in the governor’s office. “Transitions happen,” Kotek told reporters. “People move on.”

She may be one of the only people in Oregon politics who believes that.

In a March 15 memo a week before she resigned, Tibbs, the governor’s special adviser, made the underlying tension over the first lady’s role explicit, highlighting “issues that [Andrea] Cooper, Lindsey [O’Brien] and I have advocated be addressed over the last several months related to use of public resources and office budget implications with [first spouse] staff/travel etc, the need for documented role clarity/job description for a first spouse and an articulated plan to address power dynamics and reporting structure.”

Tibbs added that “the first lady should sign all the office policies and procedures ASAP since has started to be in meetings with staff/time in the office again.”

Cooper pushed on those points repeatedly. Emails show she was punished for that—first, by being excluded from meetings when the first lady was present and, later, by being fired. (Although Kotek has declined to comment on Cooper’s departure, the governor agreed to pay her eight months’ salary, $227,250, for a make-work position at the Department of Administrative Services, evidence Cooper was indeed fired. Employment lawyers say that since the state typically doesn’t pay severance, the money was probably meant to avert a lawsuit.)

Despite months of discussions about formalizing Kotek Wilson’s role, the governor’s office says the first lady has yet to sign the workplace disclosure and conflict-of-interest forms all staff must sign. That’s a signal Kotek is holding her wife to a different standard than everybody else. (The governor’s office says Kotek Wilson is waiting for guidance from the Oregon Government Ethics Commission.)

Pressed to answer whether by sacrificing her top people to make her wife happy she had put her wife’s interests before those of Oregonians, the governor said at a recent press conference, “I have not.”

Governors oversee dozens of agencies, hundreds of boards and commissions, and relationships with lawmakers and key stakeholders. They are only as good as the staff around them.

An early sign that Oregon’s longest-serving governor, John Kitzhaber, was in trouble came in 2013, when three of his top staff left three years into his third term—a remarkable parallel to the current situation (one major difference: Unlike Kitzhaber’s fiancée, Cylvia Hayes, Kotek Wilson hasn’t sought to profit from her role).

“No matter how capable a governor is, they carry a huge load,” former Gov. Barbara Roberts says. “The need for a strong staff—that goes without question.” Roberts says she doesn’t know anything about the internal workings of Kotek’s administration, but she knows what’s normal in Salem.

“When that many highly skilled, highly experienced people make a choice to leave,” Roberts says, “that’s not only surprising, it means it was intolerable.”

Related Sidebar: Meet the Five High-Level Staffers Who Left Gov. Tina Kotek’s Office