Oregon Health & Science University’s drive to buy Legacy Health hit the wall May 5, blowing up 20 months of time and likely burning millions in expenses.

But there are almost certainly survivors. Among them are attorneys at Washington, D.C.-based Hogan Lovells who advised OHSU on the deal. They like to win, but they get paid no matter the outcome.

Legacy executives, meantime, get to keep high-paying positions that might have been cut in a merged hospital system. Chief operating officer Jonathan Avery, for example, made $1.4 million in salary and other pay in the fiscal year that ended March 31, 2024, according to a Legacy tax filing. Board chair Charles Wilhoite will keep his $45,000 stipend. (OHSU’s board is all volunteer.)

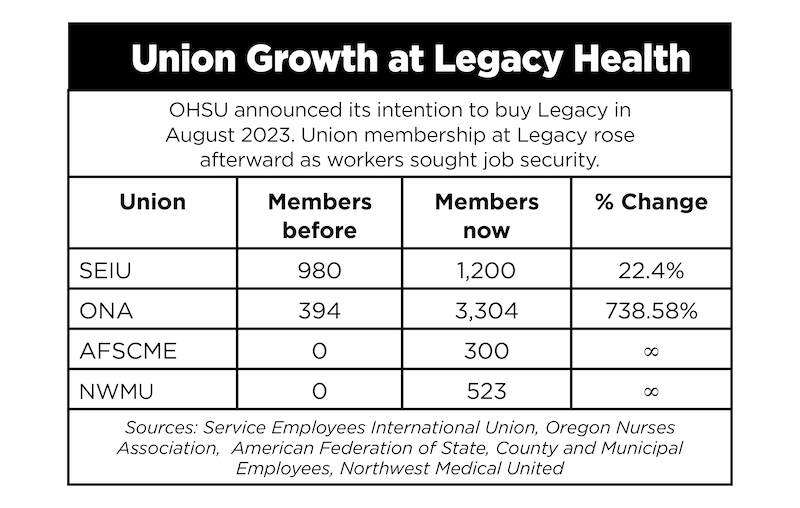

Another winner might be labor. The big three unions at OHSU and Legacy—the Oregon Nurses Association, the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, and Service Employees International Union—all expanded membership as the merger loomed, especially at Legacy, where only 1,400 of its 14,000 workers were unionized beforehand. Now, in total, Legacy has 5,350 union workers, accounting for 38% of its workforce.

The Oregon Nurses Association is the biggest winner at Legacy. Its ranks have grown from 400 to 3,300 since OHSU announced the Legacy deal. The change was less pronounced at OHSU. The nurses’ union added 635 new members, bringing the total to 4,900. Almost 80% of OHSU’s workforce is unionized.

OHSU and Legacy wanted to combine in part because they thought they could lower costs as a single entity. Ironically, the whole exercise is very likely to push up labor costs, especially at Legacy, as new union bargaining units negotiate their first contracts.

On its website, the Department for Professional Employees, a coalition of 24 national unions managed by the AFL-CIO, lists salary increases for newly organized nurses at Central Vermont Medical Center (21.5% over the course of the contract), Kapiolani Medical Center, Hawaii (3.5% annually), and at a unit of PeaceHealth in Oregon (16% over four years).

That’s good news for workers and bad news for OHSU and Legacy because only in California and Hawaii do nurses make more than in Oregon, according to industry publication Becker’s Hospital Review. Adjusted for Oregon’s lower cost of living, nurses here are the highest paid in the nation.

Those high wages have squeezed profits, according to the Hospital Association of Oregon. In 2023, the last year with comparable data, Oregon hospitals had an average operating profit margin of just 0.94%, compared with 5.2% for hospitals nationwide. It was poor margins that drove Legacy toward OHSU’s arms, and those margins are threatened anew.

Legacy’s press department declined to comment on the labor situation.

Unions turbocharged their push shortly after OHSU announced its intention to buy Legacy in August 2023. OHSU said it would sell $1 billion of bonds and use the proceeds to refurbish Legacy’s aging hospitals and clinics. Despite that promised largesse, employees knew that mergers often meant redundancies, and that redundancies meant layoffs.

“People were unsure about the future, and they found a home with Oregon AFSCME,” says that union’s spokesman, David Kreisman.

To be sure, all workers could suffer if a cost-cutting private equity firm swoops in and buys Legacy. But for now, unions are enjoying a membership expanded by a deal that’s dead.

Labor support was critical to the merger’s prospects from the start.

OHSU announced the deal a week after the Oregon Nurses Association declared an impasse in monthslong negotiations with the academic medical center. The next day, ONA chastised OHSU for promising $1 billion for Legacy while stonewalling nurses.

“While nurses at OHSU have been at the bargaining table looking for management to step up and do what is right for their nurses and their patients, OHSU’s management have been short-changing the nurses in their contract offers while also pledging more than $1 billion over 10 years to an acquisition,” ONA said in an Aug. 17, 2023, statement.

But for all that bluster, nurses didn’t actually want the deal to die. They loathed Legacy for attempting to close a birthing center at its Mt. Hood Medical Center, and, well, the enemy of your enemy is your friend.

“ONA does not have any faith in Legacy’s management, so a merger with a public institution like OHSU—which will come with more requirements related to transparency and accountability—is likely to be in the best interests of Legacy’s patients and their 13,000 staff members,” ONA said at the time.

That November, three months after the announcement, 200 hospitalists—doctors who work only in hospitals—voted overwhelmingly to join a union that’s now called Northwest Medicine United. It was a big deal because doctors hadn’t been union members until recently, when changing economics in medicine forced many out of their own small practices and into health systems.

The movement gained momentum that December, when 17 doctors at Legacy women’s health clinics said they planned to organize through Northwest Medicine United. The union has more than 500 members at Legacy now, in a variety of positions.

AFSCME, meantime, won two bargaining unit elections last week, one at Legacy’s Emanuel Medical Center, and another at Randall Children’s Hospital, adding 225 workers. Another vote, at Legacy’s Mount Hood Medical Center, is scheduled for next week, Kreisman of AFSCME said.

Unions came out in strong support for the merger early on, a move that surprised Dr. John Santa, a physician and Oregon health policy expert who trained at Good Samaritan Hospital and later worked there.

“I thought it was odd that they played their cards so early on and lost some leverage,” Santa tells WW. “If I were them, I would have stayed neutral for a while.”

OHSU made a concerted effort to win union approval. Under the leadership of then-president Danny Jacobs, OHSU said it wouldn’t lay off any unionized workers for 12 months after the Legacy deal closed. Nonunion workers got just a six-month guarantee. OHSU also pledged to invest $10 million in “education trusts” to train workers.

Those perks, plus the chance to have an anti-union Legacy subsumed into a union-friendly OHSU, kept labor on management’s side as it dealt with regulators. Last October, ONA, AFSCME and SEIU submitted a joint letter, along with Basic Rights Oregon, to the newly created Health Care Market Oversight unit of the Oregon Health Authority, applauding the deal.

“While consolidation can have negative consequences, we must accept the realities of the current moment,” the unions wrote. “Legacy Health is struggling financially and maintaining the services they provide is essential. We believe OHSU is the best entity to make this acquisition because Legacy will continue to be accountable to the people of Oregon—unlike acquisitions by private equity or large, out-of-state for-profit hospital operators.”

The merger might be off, but the unions still have new members recruited when it looked like organizing might be the best way to protect against layoffs. And they intend to keep organizing.

“We’re proud of the work we’ve done to help these workers,” Kreisman at AFSCME says. “People are still looking to unions for the protections and benefits they deserve.”