The first child infected with measles visited an urgent care clinic in Vancouver, Wash., on New Years Eve. A little more than two weeks later, at least 18 more kids and one adult in Clark County, Wash. had contracted the virus.

One contagious kid attended a Portland Trail Blazers game on Jan. 11, potentially exposing the disease to any of the 19,393 people in attendance who hadn't been vaccinated. There have not been any confirmed measles cases in Oregon.

Even as the outbreak spread in Washington, the World Health Organization declared "vaccine hesitancy" to be one of the top ten threats to public health in 2019.

"Measles, for example, has seen a 30 percent increase in cases globally," the WHO wrote in its report on the top ten threats. "The reasons for this rise are complex, and not all of these cases are due to vaccine hesitancy. However, some countries that were close to eliminating the disease have seen a resurgence."

Anti-vaxxers, or people who choose not to vaccinate themselves or their children, have been on the rise in recent years, and many communities in the Pacific Northwest have seen a sharp decline in vaccination rates.

The Oregon Health Authority found that the number of kindergarteners seeking a non-medical vaccine exemption rose to 7.5 percent in 2018, the highest since new laws were passed to make obtaining the non-medical waivers more difficult in 2015.

Clark County's vaccination rates are also unimpressive. In 2017-2018, 76.5 percent of kindergarten students had completed all of their vaccinations in Clark County. 13.5 percent of kids were out of compliance. 1.2 percent had a medial exemption and 6.3 percent had a personal exemption. 0.4 percent had a religious exemption.

84.5 percent had completed their measles vaccine.

Measles can be deadly. Before the vaccine was introduced in the early 1960s, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recorded more than 3 million measles cases each year. More than 400 people died from the virus, and another 1,000 developed brain swelling that left many people with brain damage.

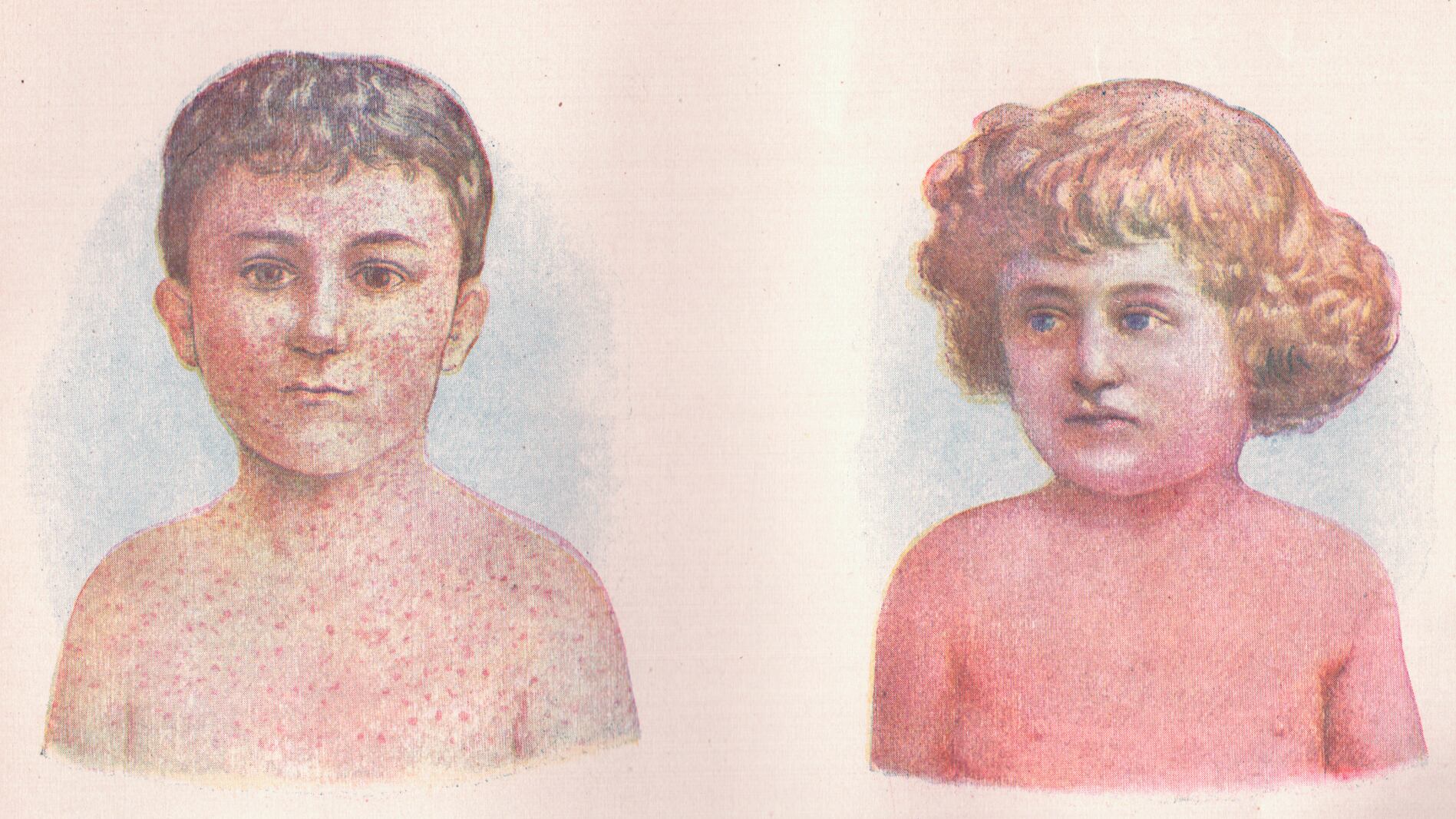

The highly contagious virus spikes a fever and comes with all of the usual signs of illness: coughing, sneezing, runny nose, red eyes. But then a bumpy red rash spreads from the patients head down across the rest of the body. A child with the measles will be contagious for four days before the tell-tale rash appears.

Luckily, the measles vaccine is incredibly effective. In fact, the Clark County Public Health agency advised after the first case was confirmed on Jan. 4 that everyone up-to-date on their vaccinations could consider themselves immune to the virus.

Since the U.S. started giving people shots to prevent the disease, the nation has seen 99 percent fewer measles cases. People almost always catch the virus abroad and bring it back, spreading it to others who have not had their shots.