The Metro Council today began discussing how and whether to keep building affordable housing, now that proceeds from a $652.8 million housing bond voters approved in 2018 have nearly all been allocated.

Metro chief operating officer Marissa Madrigal publicly introduced a concept that Metro has been quietly discussing behind the scenes with various interested parties: diverting money from a 2020 homeless services tax that Multnomah, Clackamas and Washington counties have struggled to spend. (Part of the problem is that tax receipts continually exceed forecasts.)

The good news: Metro expects the 2018 housing bond to produce 4,700 new affordable housing units, 20% more than the 3,900 units the regional government promised voters.

The bad news: Even with that increase (which includes 1,600 units of “very affordable” housing for people making 0% to 30% of median family income), the region remains woefully short of low-income housing. “We can’t afford to fall further behind,” Madrigal said.

Metro, however, is in a bind: Taxpayers will continue to pay off the 2018 bond until 2038, so the agency cannot issue another bond without raising taxes. It doesn’t want to do that, and Gov. Tina Kotek has urged local governments not to raise taxes for at least three years.

“Voters don’t have much appetite for new taxes,” Madrigal told the council.

But there is an alternative within reach, Metro officials said. The Metro supportive housing services tax on high-income households is generating far more revenue than economists projected in 2020 when voters approved it.

In November, Metro released a forecast showing the agency expects the measure to generate $356 million this year and to increase steadily to $437 million in 2029. That’s way more than the $250 million a year voters were originally told to expect.

Today, at a council work session, Metro proposed pulling together a panel of experts and interested parties to consider various options for what to do after the housing bond is finished. One option, of course, is to do nothing.

Another option, and the one that is likely to generate the most conversation, is whether to ask voters to allow Metro to shift some of the excess homeless services revenue to construction, rather than just providing services. (And, possibly, to extend the expiration of the homeless services tax, which currently sunsets in 2030.)

There are a couple of reasons to think that shifting some money to housing could gain traction. First, the big three counties that receive revenue from the measure, Multnomah, Washington and Clackamas, have struggled to put the money to work. Multnomah County, in particular, has fallen far behind its budgeted spending schedule. The second reason is logic: It makes more sense to provide services to people if they have permanent housing.

“That is potentially the strongest path forward,” Madrigal said, noting that both housing advocates and business groups have reacted positively in preliminary conversations.

There is recent precedent for course correction when tax revenues exceed forecasts. The city of Portland recently repurposed $540 million in future revenue from the Portland Clean Energy Fund from vaguely defined uses to fill budget holes in various city agencies.

In order to generate support for shifting some of the homeless services measure to housing, Metro is probably going to have to change the mechanism by which it taxes residents. Currently, individuals who make $125,000 or couples who make a combined $200,000 pay an income tax of 1% of their incomes above those thresholds. Corporations with gross revenues of $5 million or more pay a 1% income tax on profits.

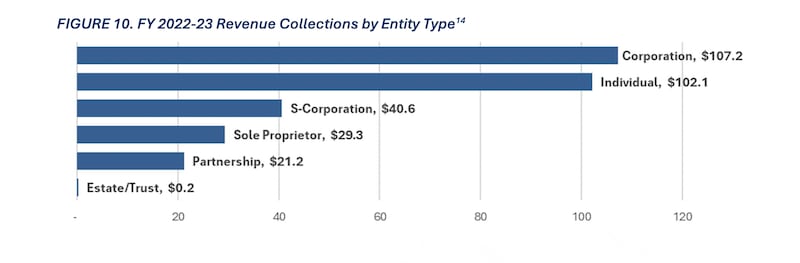

Here’s how the revenues from the tax break down by source:

Advocates for the business community will want stronger oversight of tax dollars and concessions from Metro for their support or lack of opposition. Those concessions would probably include raising the threshold for paying the tax and indexing that threshold so it increases over time to account for inflation.

Jon Isaacs of the Portland Metro Chamber (formerly the Portland Business Alliance), which endorsed the original supportive housing services Measure, says his group and other business organizations like the idea of shifting homeless services money to housing and building more units.

“We see an opportunity to build more affordable housing without doing the same thing—raising or adding taxes—over and over,” he says. Isaacs says polling suggests voters would also be supportive of what he calls “reforming” the supportive housing services measure. “We have a chance to fix the measure,” Isaacs says. “This could be a real lifeline.”

Echoing her colleagues’ support for considering changes to the measure, Metro President Lynn Peterson said that to create stability within the affordable housing realm is crucial. Peterson said Metro must balance sometimes conflicting constituent needs.

“We are hearing grave concerns about financing and taxation and grave concerns about housing and homelessness,” Peterson said. “We have to figure out how to address both at once.”

Metro councilors responded positively to Madrigral’s proposal to pull together a group to evaluate various options. Madrigal now plans to convene a “Regional Housing Stakeholder Advisory Table” with the hope that it can create a plan by May.