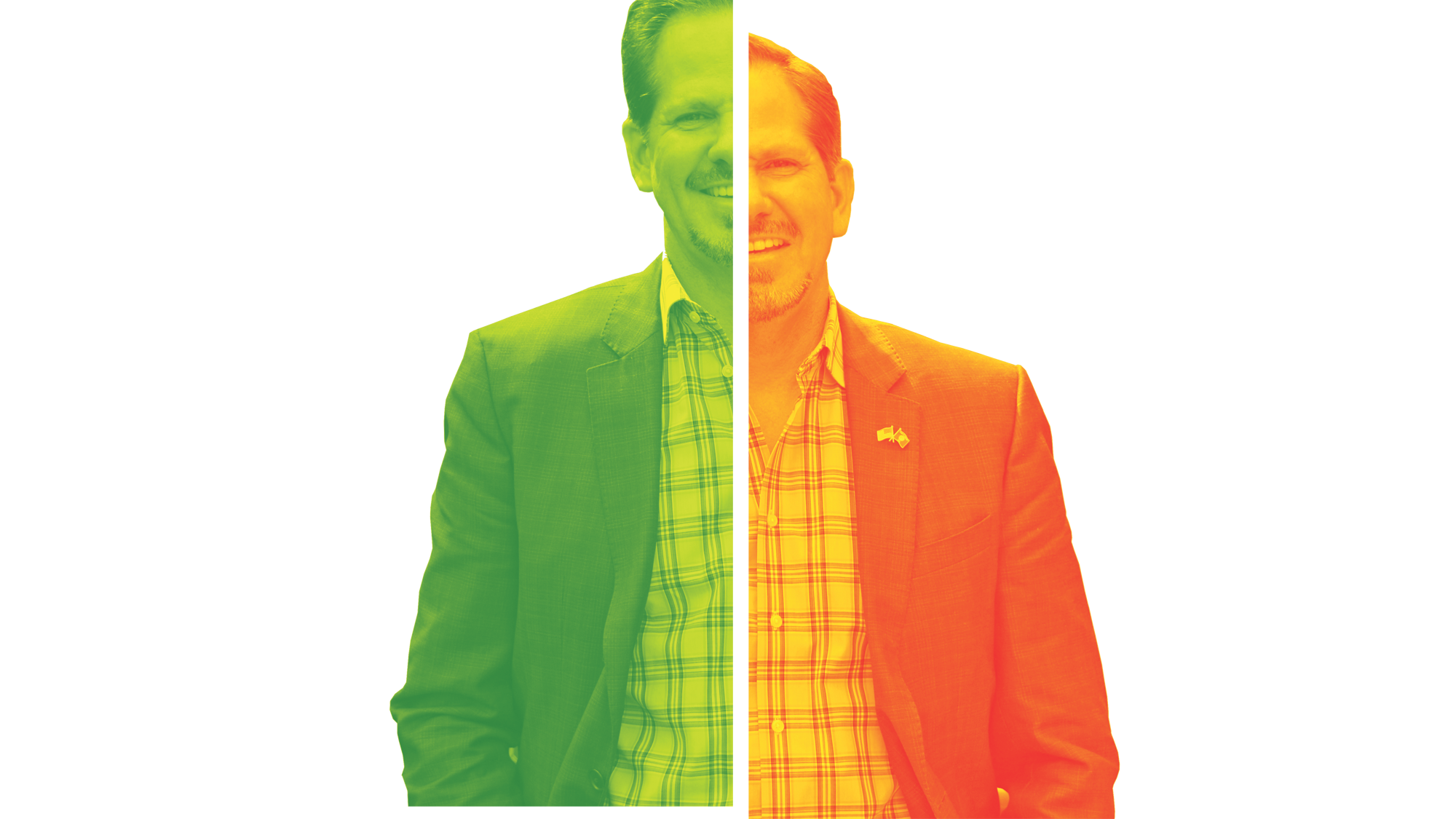

The squabble started soon after state Rep. Knute Buehler (R-Bend) announced his run for Oregon governor.

In an Aug. 3, 2017, interview with his hometown newspaper, The Bend Bulletin, Buehler called himself "pro-choice."

Grayson Dempsey, executive director of NARAL Pro-Choice Oregon, hit back immediately with an op-ed in The Oregonian, saying Buehler was merely "masquerading" as pro-choice.

That began a strange dance that continued through Buehler's victory last week in the Republican gubernatorial primary, and now creates a puzzling dynamic heading into his faceoff with incumbent Gov. Kate Brown in the general election.

Buehler swears he's pro-choice. Groups that advocate for abortion rights say he's lying.

Campaign experts say the criticism is aimed at dulling Buehler's appeal among nonaffiliated voters, a large and rapidly growing slice of Oregon's electorate that offers Buehler his best chance of victory in November.

Buehler, a 53-year-old orthopedic surgeon, understands how hard it will be to win statewide if there is any daylight between him and Brown on abortion. Oregon is arguably the most pro-choice state in the nation.

"I was pro-choice long before I decided to run for office, and I am pro-choice today," Buehler tells WW. "What has changed are the various activist groups' litmus tests on this issue."

NARAL's Dempsey acknowledges the nuances of reproductive rights can be confusing and that there is no single definition of "pro-choice," but she points to two votes Buehler cast against bills that would have solidified women's access to abortion. She also offers an analogy.

"If a candidate says he's an environmentalist and every environmental group comes out against him," she says, "who are you going to trust?"

Abortion law has been settled nationally for decades, and Oregon offers some of the nation's broadest and strongest protections for the procedure. So it behooves Buehler to make abortion a non-issue ASAP.

"He's doing the right thing in saying, 'I'm more moderate, so don't hold social issues against me,'" says Jim Moore, who teaches political science at Pacific University.

Moore and other observers say Gov. Brown, a Democrat, is the clear favorite in the November general election.

Registered Democrats outnumber registered Republicans in Oregon by 261,000 voters, a 10 percentage-point advantage. That mismatch in voter registration is a big reason Republicans have not won an Oregon governor's race since 1982.

The opportunity for Buehler lies in the massive block of voters—currently 836,000, nearly a third of the electorate—who are not registered with either party. (In 2010, when Republican Chris Dudley nearly defeated Democrat John Kitzhaber in the governor's race, there were just 425,000 nonaffiliated voters, or NAVs.)

"NAVs have traditionally leaned to the left on social issues," says pollster John Horvick of Portland's DHM Research. "They tend to be more like Democrats on social issues and more like Republicans on fiscal issues."

Horvick and Moore both say economic issues—jobs and taxes—are higher on voters' list of concerns these days than reproductive choice.

"Choice is a binary issue for most people," Moore says. "They are either for it or against it, and there isn't much movement or desire for discussion."

On economic issues such as government spending and taxes, Buehler is clearly more conservative than Brown. He's says, for instance, that if elected he won't sign a spending bill until lawmakers agree to significant pension reforms.

But on social issues, there's less distinction. Buehler supports same-sex marriage and was one of three House Republicans to vote for a gun control bill passed earlier this year. Those positions mirror Brown's—and could appeal to nonaffiliated voters.

Buehler says the criticism of his record on choice stems from left-leaning groups that fear he'll attract moderate Democrats and unaffiliated voters.

"It expands the possibility of support, and that's what highly partisan operations are concerned about," Buehler says. "They understand that a fiscally conservative, socially accepting Republican is a big problem for them. That's why the attacks are coming."

That may explain why pro-choice groups amped up their criticism of Buehler last week, holding a joint press conference the morning after he won the GOP nomination, beating two pro-life opponents, Bend businessman Sam Carpenter and retired Navy pilot Greg Wooldridge.

The groups hitting Buehler on choice include NARAL, Planned Parenthood Advocates of Oregon, the Democratic Party of Oregon, and EMILY's List, a national organization that supports women candidates.

Activists are trying to focus voters on Buehler's votes against 2015's House Bill 2758, which increased privacy protections for insured parties seeking medical assistance, such as abortions, and especially HB 3391. That 2017 bill codified the legalization of abortion in Oregon law (in case Roe v. Wade were overturned) and mandated that all Oregonians, including undocumented immigrants, receive birth control, including abortions, at no out-of-pocket cost.

Buehler says he opposed HB 2758 because he thought it changed the existing system too quickly and also abridged parental rights to disclosure. He says he oppposed HB 3391 on financial terms, because it expanded and increased spending while lawmakers were cutting existing programs.

"We must prioritize protecting existing services," he says, "especially those that are matched with federal funds, before adding new ones, which are not."

Dempsey says Buehler is operating out of a national "faux-choice" playbook, trying to have things both ways.

"You can't say you are pro-choice and take a "no" vote on abortion," she says.

Buehler says he's proven his commitment to reproductive rights with the passage of a 2015 bill that allowed women to obtain birth control medications without seeing a doctor. He thinks his party affiliation is the real issue.

"I'm a different kind of Republican," he says, "and that is a threat to them."