This story, titled “The Boys Next Door,” originally ran in the May 27, 1998, edition of WW.

Can a young man have two faces?

Can he be a choir boy and a cold-hearted robber? A student body president who, in his spare time, points pistols at cashiers?

Authorities in charge of an intense investigation into a series of gunpoint robberies say yes. They point to two popular Grant High School students: Ethan Thrower, who sings with an elite choir, and Tom Curtis, the student body president. The two have been identified as suspects in up to 13 armed robberies that terrorized businesses around the school, according to court testimony. Law enforcement sources confirm that they’re expecting a sweeping indictment soon.

Thrower, 18, has already been arrested in connection with one of the crimes, an armed robbery at Rustica restaurant. Shortly after the arrest, Curtis left school and hasn’t been seen since.

Although the allegations against the Grant students are far less dramatic than those against Kip Kinkel, authorities in both Springfield and Portland are asking the same question: At what point does youthful rebellion become a harbinger of criminality? All three come from two-parent families. None of them seems to have a problem with drugs, and their upbringings are solidly law-abiding middle-class.

Thrower is a track star and an honor roll student with a scholarship to West Virginia Wesleyan College. Curtis, also a top runner, is an Eagle Scout and a volunteer at a women’s shelter.

With backgrounds like these, the big question is why.

“This isn’t tidy,” says Val Owen, a Multnomah County sheriffs deputy who evaluated Thrower for bail eligibility. “They weren’t poor. They weren’t part of a gang. They weren’t using drugs. That’s what’s scary about it. It’s in our own backyards. It’s your own children. It’s ‘us’ instead of ‘them.’”

Northeast Portland’s Grant High School is the classic public school. Its 74-year-old halls attract all sorts of students, ranging from those who

live in high-priced homes along the Alameda ridge to those who come from the modest bungalows in Rose City Park. Its 1,800 students make it the biggest school in the district, and more than 35 percent of the students come from minority backgrounds.

It also has a reputation for being among the best, if not the best, public high school in the city.

From the performing arts program (the school staged a production of Oliver last year with a 650-member cast) to the storied traditions of its athletic teams to the celebrated honors programs, Grant is recognized citywide as an urban school that works. Toni Hunter, a no-nonsense administrator with a soft voice and tightly pulled-back braids, has been the school’s principal for just eight months but says that since she came to Portland Public Schools in 1973, her goal has been to get to Grant.

The school has had its share of problems nonetheless. Former students remember the fights in the halls, the reputation for gangs and a nagging class-based rivalry with wellheeled westside schools. A murder near the school eight years ago scared scores of kids into transferring, even though the incident had nothing to do with Grant. In the past few years, however, the bad reputation has slipped away and now the school is perceived as safe.

In this environment, Tom Curtis rose to become student body president.

Fellow students say Curtis has always been one of the most popular students on campus. He’s quick-witted and sharp-tongued, and smart enough to excel, but he directed his talents instead toward athletics. Last year, Curtis placed third in the city in the 800-meter event. Most people describe him as a generally likable fellow, although staffers say his humor has on occasion crossed into offensiveness.

On Feb. 3, students gathered in the auditorium to hear campaign speeches by Curtis and another candidate for student body president. Upon taking the stage, Curtis launched into a humorous but pointed attack that “hurled insults at the entire Grant staff,” according to the student newspaper The Grantonian, “specifically targeting a few members.” He called one staffer a troll, according to a teacher who was there, and made fun of another’s weight problem.

The speech brought down the house, and Curtis won the election.

Some students were puzzled by the performance, because Grant requires campaign speeches to be pre-approved. Vice Principal Joe Simpson told WW that he read Curtis’ speech before it was delivered and tried to get him to tone it down, but Curtis wouldn’t cooperate. “The conversation he and I were having went nowhere,” Simpson says, adding that Curtis claimed his First Amendment rights to free speech.

“There were never any threats of suing,” Simpson says, “but anytime somebody talks about their rights, [you know that] if you violate those rights there could be trouble.”

This wasn’t Curtis’ first encounter with Simpson, the school’s disciplinarian. The pair had several talks over the years, although Simpson refuses to discuss details. The Curtis family also refuses to comment. WW has learned, however, that on several occasions, Curtis was suspended from school for behavior problems.

“It hasn’t been a cakewalk dealing with some behavior issues and attitudes [of] Tom Curtis,” Simpson says. “He was one to push you. He wasn’t just going to jump because you asked him to.”

Simpson also got to know Curtis’ father, James, a lawyer and a senior vice president at the Bonneville Power Administration. Sometimes, Simpson says, he felt like he was being “cross examined” by James Curtis, although in the end, the senior Curtis usually came around if his son was out of line.

Curtis’ best friend was Ethan Thrower.

The two became friends through the track team, on which both earned accolades. Last year, Thrower scored first in the city in the 400-meter dash and was voted Most Valuable Player. As underclassmen, Curtis and Thrower were involved in a little healthy competition: one year, Thrower was voted Homecoming Prince, the next year Curtis won the title, and the third year they shared the crown. As a senior. Thrower was voted Homecoming King.

But the two come from different backgrounds. Thrower, the third of four children, grew up in a rental home near Grant. His father, George Thrower, is a shoe repairman; his mom, Kandi Kaiser, provides childcare in their home.

“Education has always been the most important tiling in our family,” Kaiser says. When Thrower and Kaiser discovered in first grade that Ethan was severely dyslexic, they paid for tutors to make sure he kept pace academically.

With that extra help, and lots of tenacity, Thrower excelled. He made the honor roll in the first semester of his senior year, and his grades have generally been above average. Both teachers and fellow students admire his hard work and his winning personality. “He was blessed,” says one fellow athlete. “He could fit in with every single crowd.”

Thrower sang in the school choir for several years, and last year won a spot on the Royal Blues, a 28-person choral group that performs a grueling 40 times a year. According to choir director Doree Jarboe, Thrower competed with 150 hopefuls for one of the eight slots that were vacant last year. “[Jarboe] looks for people who have something special to offer,” a former choir member told WW. “She obviously found that in Ethan.”

“I pick the kids pretty carefully. They’re go-getting kids,” Jarboe told WW.

Somehow Thrower was also able to hold down a part-time job. In November, he started working as a busboy at Chez Jose on Northeast Broadway, a job that manager Michelle Sweeney says he took seriously.

“He was one of those highschool kids you don’t meet very often,” she says. “He was a wonderful person. He looks eye-to-eye with you, he’s not afraid of adults, not shy. He was a great employee.”

Police first encountered Thrower and Curtis in August 1997.

According to a Portland Police Bureau report, Curtis and Thrower were together when Curtis got into an altercation with a clerk at the 7-11 at Northeast 46th Avenue and Sandy Boulevard. Curtis allegedly walked out

of the store without paying for some snacks. The clerk followed him outside, and Curtis took a swing at her. A Portland cop with a police dog happened to pull up just before Curtis’ hand connected with the clerk’s cheek. Curtis ran, according to the report, and the officer followed. In their reports, officers describe what ensued as a “riot.”

With Curtis in the lead and the officer and K-9 following on foot, a group of fellow students, led by Thrower, joined in the chase. Some, including Thrower, were shouting obscenities at the cop, who wrote in a report that he felt so threatened by the group that he called for emergency backup.

When Curtis was arrested, he was belligerent, according to the report. “[Curtis] was very angry and hostile,” Officer Kurt Sardeson wrote in the report. “[He] refused to keep his hands in view.... All the while [Curtis] was threatening to sue and demanding badge numbers. He cursed at me repeatedly.” He later apologized to the cops, referring to himself as a “jackass” and saying he was prepared to accept the consequences, according to the report.

On April 9, 1998, Curtis was acquitted in juvenile court of third-degree robbery. (Transcripts of juvenile proceedings are not available under public records law, so it’s difficult to figure out what happened.) A friend joked about the so-called robbery as the “Twinkie incident” and told WW that the only reason things got out of hand is because Curtis was provoked by the clerk.

“You’re not looking at the profile of a serial robber,” she told WW.

Cops now think otherwise.

Meanwhile, in November 1997, Curtis got in trouble with the law again, this time for initiating a false police report. As police describe the incident, Curtis and Thrower pulled into the parking lot of Everyday Music in Curtis’ black Acura. Curtis called 911 to get medical help for Thrower, who had suffered a gunshot wound to the scrotum. Thrower initially said he was shot by someone else, but quickly changed his story and admitted that a gun shoved in his waistband accidentally went off. Curtis, who was questioned separately, maintained that Thrower was shot by gang members.According to a police report, he actually took them to the spot where the “shooting” took place.

Police later went to the Curtis home looking for Tom and met his father. “Mr. and Mrs. Curtis became intense and wanted to know what I would do with their son,” Officer John Butler wrote in the report. “Mr. Curtis became aggressive and stepped from the front hallway and opened the front screen door and stated. What gives you the right to arrest him?... “Who do you think you are? Judge and jury?” The officers decided to leave because Mr. Curtis was so “aggressive and upset.”

In January, Curtis pleaded guilty to filing a false report and told the judge another version of the story: “I was driving one night and took a corner too fast. I was not aware that my friend had a gun under his belt.

As I took the corner, I guess it went off...he was yelling. It was his dad’s gun and he said his dad would kill him if he found out he had his gun.”

When Judge David Gernant asked Curtis at the hearing how he felt about the incident, he replied, “I think it’s really changed my senior year.”

“Do you feel stupid or embarrassed?” the judge prompted.

“Yeah,” Curtis replied. “We’ve heard it from the students at school.”

He was sentenced to probation and ordered to apologize to the officer and pay a fine.

That would have been the end of the story if it weren’t for some smart detective work.

Lying to police about an accidental gunshot wound is hardly a capital offense. But one aspect of the case made the cops very interested: Curtis’ 911 call came just minutes after two men in ski masks had barged into Rustica, a Northeast Portland restaurant, waving guns and demanding cash.

According to patrons who witnessed the robbery, the two men were dressed similarly in jeans, black jackets and black ski masks. One went straight to the cash register. The other walked toward the middle of the restaurant. “Everybody be cool and nobody gets hurt,” one patron told WW this robber said. The other robber told the cashier to give him the money. “It was almost like seeing a movie,” one diner told WW “It was very surreal.”

In less than a minute or two, they were done. On the way out, “one said, ‘sorry to have interrupted your Saturday night.’ They were polite robbers,” a patron told WW. Then they hopped into a getaway car—a gray-and-red Chevy Suburban that had been reported stolen earlier that night.

The Suburban was later found abandoned near Northeast 27th Avenue and Halsey Street. A black ski mask was found at the scene, and the passenger seat was covered in blood.

To police, the Rustica holdup was unusual.

Businesses aren’t the preferred target for most crooks. Of the more than 2,000 reported robberies in Portland each year, most are what police call street robberies: someone confronts a victim on the street and demands his money.

The fact that the perpetrators at Rustica were wearing ski masks made it all the more interesting. Although it might not seem that way on TV, this type of crime doesn’t happen very often in real life. But between November 1996 and November 1997, police say the area around Grant High School was hit with 12 similar masked holdups of businesses ranging from Burger King to Barnes & Noble (“Crime Spree,” below).

Although the victims couldn’t see the perpetrators’ faces, they generally believed the robbers to be young men. Sometimes they described one suspect as black and the other as white. Often the robbers took the entire cash drawer, rather than just the money.

Because crooks generally use the same techniques, or “MO,” the police suspected the same people were involved in each robbery. But for months, they were without a solid lead.

The Chevy Suburban gave them the clue they needed.

When police performed DNA tests, they found that the blood from the Suburban matched Thrower’s. They pieced together this story: Thrower and Curtis allegedly robbed Rustica and apparently took off in the Suburban. After Thrower shot himself, they dumped the car, got into Curtis’ Acura and sped off to call 911. A third young man, Todd

Seymour, Grant’s student body vice president, is suspected of participating in the robbery as well, according to authorities.

Thrower was arrested April 16, the day before the senior prom. Curtis went to the prom but hasn’t been in school since. Authorities aren’t sure where Curtis is, but they believe he’s no longer living at home. Curtis’ parents have told authorities they don’t know where their son is. Since he has not been charged with anything, his absence in itself isn’t a crime.

Last week, Thrower appeared before Multnomah County Circuit Court Judge Roosevelt Robinson in hopes of being released pending the Rustica robbery trial. Despite receiving dozens of letters from Thrower’s supporters, Robinson turned him down. The fact that Thrower, along with Curtis, is a suspect in 12 additional robberies didn’t help his case.

The choir boy. The student body president.

Could they have committed these dangerous crimes, and if so, what were they thinking?

Detective Kelly Krohn, who is working on the case, says there may be several motivating factors. “The thing they were after was money for whatever reason, whether they needed it or not,” he said. The robbers’ take, however, was a measly $60 to $500 per robbery.

Sgt. Irv McGeachy, who is in charge of the robbery detail, thinks he knows what motivates them: “Kicks. The thrill of doing a robbery. Excitement.” He bases that idea, in part, on their MO—barging into businesses, waving guns and wearing ski masks. “It’s a bold move on their part,” he explains. “When you put yourself in a business establishment, usually there are multiple employees. You have to show your weapon to prevent somebody from jumping you.”

Owen, the sheriffs deputy who evaluated Thrower for bail eligibility, agrees. “You have modern kids talking about extreme sports,” she says. “It’s an adrenalin rush. You can think this is a new form of extreme sport.”

In this sport, however, if you slip, you face time in prison. Under Measure 11, those convicted of Robbery 1 face at least 7 1/2 years behind bars for each count.

Kaiser, Thrower’s mother, is devastated that her son is suspected in these crimes. “We’re just doing the things we can to try to salvage his life,” she said. She’s worked hard to persuade authorities to let Thrower have his homework brought to his jail cell, but graduation is now barely a dim hope.

“Our whole world has fallen apart, all our hopes and dreams for Ethan,” she told WW. “We’re grieving like someone died. That’s what it feels like. We still support Ethan. When the [pretrial release] hearing didn’t go his way he turned around and said, ‘I love you. I’m still going to be somebody.’ We believe that. This is just a setback.”

But some people feel betrayed.

“You just want to root for these kids, facing the adversity kids face these days. You have to hope. Then it shatters you when they do something like this,” says Sweeney, Thrower’s boss. “If he could fool me, what about my own kid? What’s going on out there that we don’t know about?”

Editor’s note: Tom Curtis fled to Mexico, where he joined some of his classmates for senior-year spring break revelry before his 1998 arrest in New Mexico became a national media frenzy. He pleaded guilty to robbery. In 2009, he was released from the Oregon State Correctional Institution and records show he lives a quiet life in Oregon.

Ethan Thrower cooperated with prosecutors. He was released from Columbia River Correctional Institution in 2006. He works in the metro area as a social worker and is the author of A Kid’s Book About Incarceration.

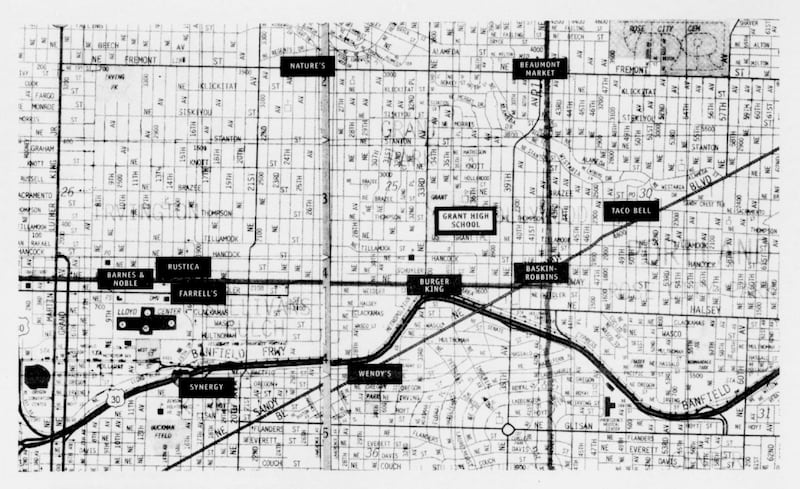

Crime Spree

Beginning in November 1996, police began noticing an unusual number of robberies in the area surrounding Grant High School. For months, they were without a suspect. Then, when Ethan Thrower was arrested and charged with the Rustica robbery last November, the case broke.

At a pretrial release hearing last week, Sheriffs Deputy Val Owen read this list of crimes into the record. According to testimony, Thrower and his friend Tom Curtis are the primary suspects. Authorities suspect a third Grant student, Todd Seymour, participated in the final two.

• 11/25/96 Baskin-Robbins on Northeast 39th Avenue was held up by two men in ski masks, reportedly one black and the other white.

• 12/30/96 A gunman held up the drivethrough clerk at Burger King at 3550 NE Broadway, where Thrower was working.

• 2/4/97 Baskin-Robbins was held up again by two masked gunmen.

• 2/5/97 A gunman flashed a chrome semiautomatic at Nature’s on Northeast 24th Avenue and made off with cash and checks. The getaway car was described as a red Volkswagen bug, which is the type of car that Curtis is known to drive, according to police.

• 2/8/97 Two robbers hit the Beaumont Market on Northeast Fremont Street.

• 3/5/97 Two men, one with a silver revolver, threaten a clerk at the Taco Bell on Northeast Sandy Boulevard and take his money.

• 4/7/97 Two gunmen rob the Wendy’s on Northeast Sandy Boulevard.

• 4/28/97 Two gunmen, one with a revolver and the other with a semiautomatic, rob the Barnes & Noble on Northeast Broadway.

• 5/11/97 In the early morning hours, Farrell’s ice cream shop on Northeast Weidler Street is robbed.

• 6/4/97 Gunmen hit the Beaumont Market for the second time. This time, one robber puts a gun to base of the clerk’s skull before making off with cash and lottery tickets.

• 7/2/97 The Beaumont Market is hit a third time.

• 11/3/97 Synergy, a retail store on Northeast 29th Avenue specializing in New Age merchandise, is robbed. Witnesses say there were three men involved.

• 11/15/97 Rustica is robbed of $454 at 10:30 pm. At the time, about 18 people were finishing their dinners.

Minutes after the robbery was reported, Curtis called 911 when a gun in Thrower’s waistband accidentally went off. After that, the string of robberies ended.

“The only thing that stopped them is him shooting himself,” Owen told WW. “It makes you wonder how far they would have taken this stuff.”