In the week prior to the 35-day session of the Oregon Legislature, a little-known political action committee whipped out its checkbook.

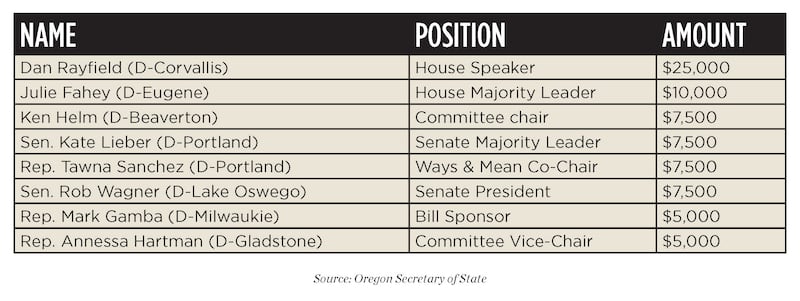

Records show the Clean Energy for Oregon PAC contributed nearly $100,000 on Jan. 29 to lawmakers crucial to the prospects of a bill that would remove state oversight of new energy facilities proposed on federal lands. The recipients included the sponsors of House Bill 4090, relevant committee members, and Democratic legislative leaders. In many cases, the Clean Energy checks were among the largest that lawmakers have ever received.

To minimize the appearance of conflicts of interest, lawmakers don’t take contributions during legislative sessions. Most of the checks from the Clean Energy PAC, however, arrived less than a week before session began Feb. 5.

What’s more, the Clean Energy for Oregon PAC is nearly entirely funded by a single company: NewSun Energy, a Bend- and Tucson-based solar developer.

Jake Stephens, the founder and CEO of NewSun, says he gave the money to support lawmakers in both parties who share his urgency about reducing carbon emissions.

“Climate action is the challenge of our time,” Stephens says. “We are out of time. After decades of the fossil and utility industries stalling out and watering down action, Oregon must make steady, clear, regular progress, every single session, every single year.”

Entities with business before the Legislature regularly contribute to the campaigns of relevant lawmakers. But Stephens’ gifts were unusual in their timing, generosity and specificity (see a list of top recipients, below).

They also place environmental leaders in an unusual position: standing in the way of legislation Stephens and his allies say is vital to Oregon’s green energy transformation.

Nobody has pushed harder to wean Oregon from fossil fuels than environmental groups such as the Nature Conservancy, Sierra Club and Oregon Wild. But in the current legislative session, nobody is fighting harder against NewSun’s proposal.

“The Sierra Club strongly supports scaling up renewable energy, but we first have to make sure we aren’t doing harm,” says Damon Motz-Storey, director of the nonprofit’s Oregon chapter.

At issue: House Bill 4090, a bill that Stephens’ PAC pushed for that would speed the approval of industrial-scale energy production and transmission lines on federal lands. Currently, such projects require federal approval under the National Environmental Policy Act and a second vetting by the Oregon Energy Facility Siting Council. The bill would remove the latter body from having a say.

Stephens hoped the concept would be part of successful 2023 legislation aimed at speeding up green energy development more broadly.

When lawmakers failed to include that provision in a bill they passed, Stephens decided to bring a bill back in the 2024 short session—and he put his money where his mouth is.

Stephens says he supports “practical-minded, pro-renewable energy, pro business, rule-of-law moderates willing to work on bipartisan climate action-accelerating legislation,” adding, “Clean Energy for Oregon’s support of Oregon candidates is focused on these broader principles, not any specific bill.”

Motz-Storey doesn’t buy that explanation. “It’s bad public policy to let our environmental standards be driven by a single company’s desire to create a market niche,” he says. “The timing of it looks bad—and nearly all the folks considering this bill got money. It very much appears to be a pay-to-play dynamic.”

For more than 15 years, Democrats have pushed through a series of new laws meant to speed Oregon’s transition to green energy. Those laws have provided incentives for wind and solar power development, mandated the closure of the state’s last coal-fired power generation plant, and adopted ambitious greenhouse gas emission reduction targets.

Stephens, whose company has developed commercial solar plants in Lake and Harney counties, says the state isn’t going nearly fast enough. He and others often point to a proposed 290-mile transmission line from Hermiston to Hemingway in southeastern Oregon. Idaho Power applied for a permit in 2008, but because of permitting roadblocks, construction didn’t begin until 2023.

Stephens has been battling the state’s giant investor-owned utilities, Portland General Electric and PacifiCorp, at the Oregon Public Utility commission, arguing that existing climate legislation protects the utilities’ interests rather than advancing the public’s interest in decarbonization.

Now, he’s making that same argument about HB 4090.

His contention: The feds will engage in a rigorous NEPA process before allowing any development on the 715,000 acres of Bureau of Land Management property. Stephens and other solar developers see the BLM property as a big part of fulfilling the state’s goals. He and allies, such as Enel Green Power North America, Sunstone Energy and PNGC Power, say it’s duplicative to have the state of Oregon also review those projects and it costs time and money.

In testimony Feb. 13, NewSun attorney Max Yoklic laid out the stakes for lawmakers. HB 4090, he said, could “shave years and millions of dollars off the permitting process.”

Shannon Souza, who sits on the Oregon Solar + Storage Industries Association board, says environmentalists underestimate the difficulty of achieving Oregon’s renewable energy goals. “There’s a lack of understanding of how profound the challenge is,” Souza says. She says most people in the renewables field agree with Stephens—they’re just not willing to be as aggressive as he is.

Environmental advocates see a different risk: Solar generation covers large footprints of land that may look to the uninitiated like featureless open range but may also serve as breeding grounds, migration corridors, or other critical habitat for species that include the sage grouse, mule deer and pronghorn (often mistakenly called the pronghorn antelope).

“Of the 715,000 acres of BLM lands in Oregon, more than 100,000 acres are known migration corridors,” Michael O’Casey of the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership told lawmakers Feb. 15.

Environmentalists note that the feds are currently reviewing their own process for approving renewable energy and transmission projects. Until those new guidelines are clarified, they say, it would be foolish for Oregon to unilaterally surrender oversight. Even more foolish: entrusting Oregon’s natural resources to unknown future presidential administrations.

“These are not a few solar panels on someone’s roof; these are giant industrial facilities surrounded by chain-link fences and razor wire, linked by miles of new roads and power lines,” says Steve Pedery, conservation director for Oregon Wild. “It is vital that plans for these things are reviewed carefully so they don’t end up paving over critical habitat.”

Pedery is upset with lawmakers, who he says are putting Stephens’ concerns ahead of the public’s interest: “This developer starts cutting large campaign checks, and suddenly waiving Oregon’s energy siting and wildlife protection rules is a priority for politicians in both parties.”

The lawmakers who got checks from the Clean Energy PAC deny they were influenced by Stephens’ money. Instead, they say they support HB 4090 because they share Stephens’ sense of urgency.

“I don’t make decisions as an elected official based on support from outside groups; I make them based on what I think is necessary to solve the challenges our state faces,” says House Majority Leader Julie Fahey (D-Eugene), a chief sponsor of HB 4090 who received $10,000. “And I fundamentally believe that we cannot solve our housing crisis or our climate crises by maintaining the status quo.”

Rep. Ken Helm (D-Beaverton), chair of the House Agriculture, Land Use, Natural Resources and Water Committee, echoed Fahey’s response. “We as a state are far beyond the aspirational goals we have set to respond to climate change,” says Helm, adding that he took that position long before he got Clean Energy’s check for $7,500. “Like many of the contributions that we as legislators receive, I was not consulted on the fact of the contribution nor the amount.”

State Rep. Mark Gamba (D-Milwaukie) is a chief sponsor of HB 4090 and the first person to testify in favor of it. (He received $5,000.)

“We cannot afford for it to continue taking up to 20 years to build transmission lines and clean energy facilities when our climate is on the verge of utter collapse,” he says. “HB 4090 will shave several years off the process.” Gamba’s campaign says he won’t take money from fossil fuel companies but is “grateful for support from his allies in the clean and renewable energy industries.”

Kate Titus, director of Common Cause Oregon, which advocates for campaign contribution limits (Oregon is one of just five states that don’t have them), says the impact of big money, no matter how well intentioned, undermines the public’s trust.

“Until we change the rules, big money buys big influence,” Titus says. “This is the way it works in Salem. That’s why we need real campaign finance reform.”