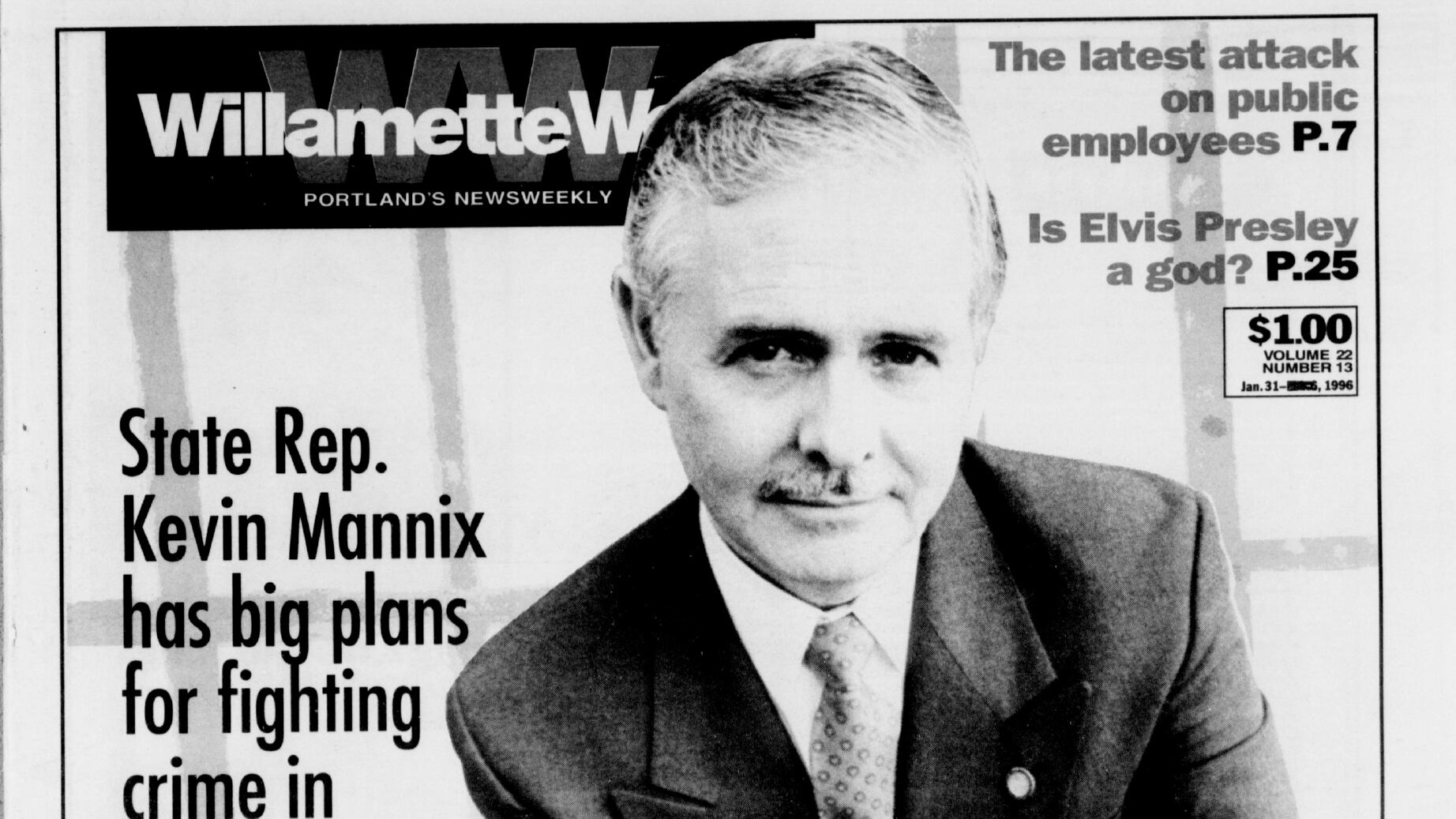

Kevin Mannix now leads an alliance of churches and Republican lawmakers who could reduce the governor's powers in a pandemic. In 1996, he was a Democrat. Our Jan. 31, 1996, cover story examined Mannix's break from his party orthodoxy.

BY MAUREEN O'HAGAN

It was billed as a conference for "Oregonians Who Are Fed Up With Crime," but the Jan. 10 gabfest at the Airport Shilo Inn could have been just as aptly labeled a "Rile-'Em-Up Republican Roundup." More than 120 people, many of them blue-suited GOP legislators, crammed into the hotel's ballroom to sharpen their arrows for the special legislative session that begins this week. How Gov. John Kitzhaber's new prison plan will release more criminals on the streets was the theme.

By the end of the day, sheriffs and judges, parole officers and district attorneys, had their say.

But the man most sought after by reporters, fellow legislators and just plain folk was state Rep. Kevin Mannix, one of only two or three Democrats who have broken ranks and opposed the governor's plan. The diminutive, articulate Salem lawyer is among the most savvy legislators in the state when it comes to corrections issues—and one of the most egotistical. Some might even call him a megalomaniac, a grandiose performer with far-reaching ambitions.

Hanging on a wall in his law office are two framed slogans. One reads, "Reports of my brilliance are highly understated." The other, "Once I thought I was wrong, but I was mistaken."

While the rest of Oregon has focused these past weeks on the U.S. Senate race. Gov. Kitzhaber has been struggling to come to grips with the seeds Kevin Mannix has sown. Two of Mannix's 1994 tough-on-crime initiatives are expected to double the state prison population in little more than five years. Kitzhaber is charged with finding space for these 6,000 additional inmates; he's drawn up a plan to do just that, and Thursday's special session was called to finance it.

But Kevin Mannix stands in his way.

Mannix, 46, who operates with the tenacity of a Doberman and the easygoing charm of a Nordstrom sales clerk, would like to topple the governor's months of hard work. Even if Mannix is unsuccessful, only a fool would count him out for good. He is currently gathering signatures for two more tough-on-crime ballot initiatives and has announced his candidacy for attorney general.

Kevin Mannix's success is an illustration of the way crime continues to grip Oregonians, even though the crime rate has fallen in many categories. It is also a lesson in the enormous difference an ambitious individual can make in this state—even if his efforts might be overreaching or fiscally irresponsible.

Dave Cook, a tough-talking former sheriff who now serves as the state's director for the Department of Corrections, begrudgingly acknowledges the impact Mannix has had on his agency: "It's like saying what a difference one anaconda can make if it's strapped around your neck."

At the Shilo Inn conference earlier this month, Mannix was introduced by his comrade in anti-crime, firebrand Lake Oswego Republican Rep. Bob Tiernan. "This, to my right," Tiernan told the crowd, "is Kevin Mannix. But shouldn't you be on my left?" he said, eliciting a burst of laughter.

Good question. Since 1989, when he first won his south-southeast Salem seat, this relentlessly cheery state representative has easily become the most enigmatic Oregon legislator in some time.

In many respects, he's a typical liberal. He's a classic tax-and-spender in the Great Society tradition. He has a solid environmental record and likes to call himself a populist who is different from other "fancy-pants legislators." He was a McGovern delegate to the 1972 Democratic National Convention.

In a few respects, however, he's anything but liberal. He's adamantly anti-choice. In his law practice, he represents corporations in workers' compensation disputes. His personal style is much more like a country-club Republican than a lunch-bucket Democrat: He sports two gold rings, an immaculately trimmed mustache and silver cufflinks that lend him a distinguished yet slightly slick image.

But the issue on which he most decidedly parts from his liberal brethren is crime.

"Kevin has probably done more to change the criminal justice system than anyone," says Dee Dee Kouns, who with her husband, Bob, directs Crime Victims United. "He's getting us moving in the right direction because he's made people talk about it."

Mannix sees his somewhat conflicted image as one of his political strengths. In fact, he thrives on it. Mannix makes a big production out of slipping in and out of his suit jacket, depending, he says, on whether he's emphasizing his liberal or conservative side. A recent television interview about a proposed law that would allow police to detain runaway youths called for the jacket, but a conversation with Willamette Week did not.

The details of Mannix's youth, which often serve to define a man's middle age, are just as hard to categorize. He was born in 1949 in Queens, New York; as the son of a foreign service officer, he bounced from place to place. Mannix celebrated his fifth birthday on a boat en route to South America. His Spanish, Mannix says his Latino friends tell him, is excellent.

By high school, Mannix was back in the United States, nourishing a strong penchant for politics. In college, at the University of Virginia, he became student body president in his fourth year. Also at UVA, he joined a Jewish fraternity even though he is a devout Catholic. "I never thought of it as a big deal at the time, but perhaps it was," he says. "Here's this Irish Catholic kid in this Jewish fraternity."

It is in these two influences—the strict moral code of Catholicism and his experiences in college—that one can perhaps find the roots of a crime fighter. Mannix says he was greatly affected by the honor code at the University of Virginia, where he earned both his bachelor's and law degrees. The policy, which was enforced by the students themselves, was tough enough to get a half-dozen students expelled every year, but fair just the same, Mannix says.

In 1974, Mannix and his wife, Susanna, a nurse, moved to Oregon. In his precise way, Mannix lists three specific reasons: Oregon's progressive government; its populist leanings, including the heavy use of initiative and referendum; and its focus on the environment.

"I think the kicker was when [Republican Gov.] Tom McCall said, 'Visit but don't stay.' When I heard that, I knew this was the place for me. Anybody that's going to be that straightforward and downright honest is expressing the values of my life." Like so many other newcomers before and since, he disobeyed McCall's command, and eventually made Oregon a permanent home for his wife and three children.

In 1975, at age 26, Mannix was hired as an Oregon assistant attorney general and got his first real taste of public service. By 1977, in search of adventure, he became assistant attorney general in Guam for two years. Then he returned to Oregon and worked as an administrative law judge for the Workers' Compensation Board, and later at a Portland law firm before establishing his own practice in Salem in 1986.

Three years later, Mannix was recruited by Neil Goldschmidt and Vera Katz to run for state representative. He has served a total of four terms in a district that's 40 percent Republican, 40 percent Democrat and 20 percent independent.

Modesty is not Mannix's forte. "I have to be careful about being self-aggrandizing and egotistical," he admits.

Yet he is quick to point out that he's introduced and passed more bills than any other legislator in his tenure. Some of his efforts were important though low-profile tweakings of the law.

Others were meticulous almost to the point of nitpicking. In his first term, he set out to abolish requirements of using registered mail and instead allow government notices to be sent by certified mail. The "giganda bill," as he calls it (it changed 56 provisions of state law), saves the state $250,00 every biennium, though it's not exactly the stuff legends are made of.

"Ninety percent of what I do as a public servant doesn't get headlines," he tells WW.

That all changed in 1993.

Earlier in his career, Mannix had pushed some crime-related legislation—one, a law protecting rape victims from having to testify in open court, another requiring sex offender registration—but most of it related to technical points of the law. Then, in 1993, he introduced a bill that mandated specific sentences for all felonies.

"I began to realize the big hole in the system was the sentencing laws," he explained. "I felt there was a certain amount of accountability lacking in the system."

His fellow legislators refused to pass his bill. "They were shy about either being tough or spending money," he says. But he didn't give up. "It was a bit too revolutionary to handle in a legislative forum," he says now. "I know we legislators are supposed to think that the legislature is God's gift to democracy, but we populists know there are a few other things out there, like initiative, to clean up problems with."

And so Mannix's controversial mode of crime fighting—the sweeping initiative—was born.

In 1994, Mannix emerged as a statewide player—sponsoring, fund-raising and acting as chief spokesman for a tough-on-crime trifecta, Ballot Measures 10, 11 and 17.

• Measure 11 called for tough mandatory minimum sentences for anyone over the age of 15. Before Measure 11, a person convicted of robbery in the second degree served an average of 24 months in the state penitentiary; under the measure, that person is required to serve 70 months with no possibility of parole.

• Measure 10 was a constitutional amendment mandating a vote by two-thirds of the Legislature to change any sentences, in order to lock these tough minimum sentences into place.

• Measure 17, another constitutional amendment, requires all state prison inmates to either work or receive alcohol or drug counseling full time.

The measures were expensive, unequivocal—and immensely popular. They were approved by 65 percent, 66 percent and 72 percent, respectively.

The consequences have not only affected Oregon's criminals, but almost every facet of the state budget, as well. According to the Legislative Fiscal Office, in the 1991 biennium, $733 million went to higher education and $593 million to public safety, which includes both the Corrections and Judicial departments. In the current biennium, $627 million goes to higher education and $752 million to public safety.

Mannix notes that spending for the governor's Oregon Health Plan has increased significantly, as well. Nonetheless, he acknowledges that he has, in fact, shifted the balance—but only because it was desperately needed.

"I don't mind spending money to accomplish positive ends," Mannix says, his tax-and-spend roots showing through. "Take a look at the votes. I think I have the pulse of the public on this."

Of that there is little doubt. But his critics say his obsession with crime will bankrupt the state.

"If he would have said here's Ballot Measure 11 and here's the surcharge we're going to put on your taxes to pay for it, you wouldn't have gotten those votes," Kitzhaber says. "It was a freebie. That's what was intellectually dishonest, to pretend that you could build 4,000 prison beds and not impact education and social programs and a whole host of other things."

Also, many criminal justice experts—from prosecutors to defense attorneys—agree that the measure was poorly drafted. Two state judges have declared Measure 11 unconstitutional, although it is still in effect and awaiting a higher court ruling. Even Bob and Dee Dee Kouns, along with Mannix himself, tried to persuade the Legislature to delete some crimes from the measure after it was approved. (Mannix and others pushed to eliminate the consensual sex crimes because there was a fear that tough mandatory minimum sentences would make victims, many of whom are related to the perpetrator, less likely to testify.)

"It was unfortunate when Kevin wrote that bill he didn't talk to some folks who were dealing with this stuff, " Bob Kouns said.

Now Kitzhaber is picking up the pieces. He has promised to build 2,312 new prison beds (and probably several thousand more) in response to Mannix's ballot measures, at a cost of $174.9 million. His budget includes $22 million to put state prisoners to work under Measure 17. He has come up with a plan—the funding of which is the primary reason for the special session—that he says will stop, or at least slow, the revolving door in and out of prison.

Kitzhaber thought he had it all figured out in June when he convinced a vast majority of the Legislature to support his innovative corrections plan. Mannix was among his supporters, even speaking on the House floor in favor of it.

Known as Senate Bill 1145, the plan calls for the transfer of state inmates sentenced to 12 months or less to the counties. Sounding almost Gingrichian, Kitzhaber touted the opportunity for local control, and the block grants in the form of jail building and operation subsidies that went along with it. But Kitzhaber's real goal was quite liberal: By funding county-level drug and alcohol treatment programs, he thought he could slow the revolving door that brings most criminals back to the system over and over. The vast majority of these SB 1145 inmates are now serving time in the state penitentiary for violating the conditions of their parole or probation.

The plan is expected to free up nearly 1,500 state prison beds, which would make room for some Ballot Measure 11 offenders who are beginning to flood the system.

"What happens now is, we bus them to a state intake center then bus them to a state facility," Kitzhaber explains. "They end up staying there for about four months and then we take them back to the community. It's very expensive. They get absolutely no treatment and they get brought back to the same place. And then they do it again."

While everyone agrees the current system isn't working, critics argue that SB 1145 will make the problem of the "revolving door" even worse.

Here's the problem. In Multnomah County, for example, the plans call for 330 new jail beds. However, the county is expecting almost 500 transferees. Officials have acknowledged that most offenders will spend less time in county jail under SB 1145 than they would have in state prison. But the heart of Multnomah County's plan is the addition of 150 beds for offenders undergoing drug and alcohol programs. County officials say this treatment will slow recidivism by getting to the root of these offenders' criminal behavior.

Mannix, who initially supported SB 1145, has now come out against it. "I'm analogizing this to mental health," Mannix says. "We made a major mistake when we said we will downsize and put the mentally ill into the communities. I think the state managed to dodge accountability of the mentally ill. Now it's a budget issue."

He believes the state should keep the money and use it to build more prisons. Mannix has even drafted a proposal, based on a gigantic Texas jail-building plan, that would cost less than the $94 million Kitzhaber has supported, and free up additional resources to devote to crime prevention.

Although Kitzhaber is convinced he has enough votes to prevail during this special session, he admits that Mannix is the man most in the way of his plans. He has one trump card: Neither Republicans nor Democrats trust Mannix completely.

"My opinion is that Kevin's approach is largely reactionary and tends to be based on a foundation of building fear in the hearts of people," says John Minnis, a Portland police officer who is also a Republican representative. "He is sincere. He is also bright enough to know these kinds of policies and objectives get him into the press." Despite his criticisms of the man, Minnis has lent his name and voice for a radio ad attacking Kitzhaber's plan.

Fellow Democrats also vilify Mannix. Kathleen Bogan, a liberal who was one of the leaders of Oregon sentencing reform in the late '80s, says, "This guy is doing a lot of damage in this state. The whole reason for these initiatives is that he's been running for attorney general since 1993.…Kevin Mannix is a man of no vision."

But Mannix doesn't let the criticism bother him.

"They can't have their cake and eat it too," he says of his fellow liberals. "They're pleased when I'm there to defend their programs, but when I'm talking about corrections, I'm the archconservative fiend. I don't have to be a clone of John Kitzhaber to be a Democrat. And he doesn't have to be a clone of Kevin Mannix to be concerned about public safety."

It's too early to tell whether Kitzhaber or Mannix will win the battle at the special session.

But it is clear that even if he loses, Mannix won't be down for the count.

Mannix is already gathering steam for two initiatives he is co-sponsoring this November. One is a victims' rights measure, which has thus far escaped controversy. The other, known as Son of 11, mandates tough minimum sentences for repeat property offenders. It is this initiative that has Kitzhaber and others fuming, not least because it will put an estimated 5,000 more people behind bars.

"The deficiency Kevin has is his eyes are bigger than his stomach," said one Democratic insider on the condition of anonymity. "[If Son of 11 passes] we might as well give half the budget to education and half to corrections and go home."

In addition to Son of 11, Mannix has other plans. After Ted Kulongoski announced that he would not seek reelection as attorney general, Mannix quickly lined up to seek that seat. He is considered a front-runner for the position, which could have great influence on this state's crime policy.

"The attorney general should not be simply an advocate for government agencies, but also serve as something of a conscience as to public policy imperatives," he explains.

Be he egoist or savior, thoughtful or irresponsible, it's clear that Kevin Mannix will be around for a long time.

And even his critics admit that some good has come of his policies. Albeit using the blunt instrument of ballot initiatives instead of a legislative scalpel, Mannix forced both liberals and conservatives to rethink an issue that has been ignored for too long.

"We got Measure 11 because a lot of people, the DA's office included, probably didn't take care of business," says Mike Schrunk, Multnomah County's district attorney. "We had gridlock."

If nothing else, Kevin Mannix is a man who can cut through gridlock.