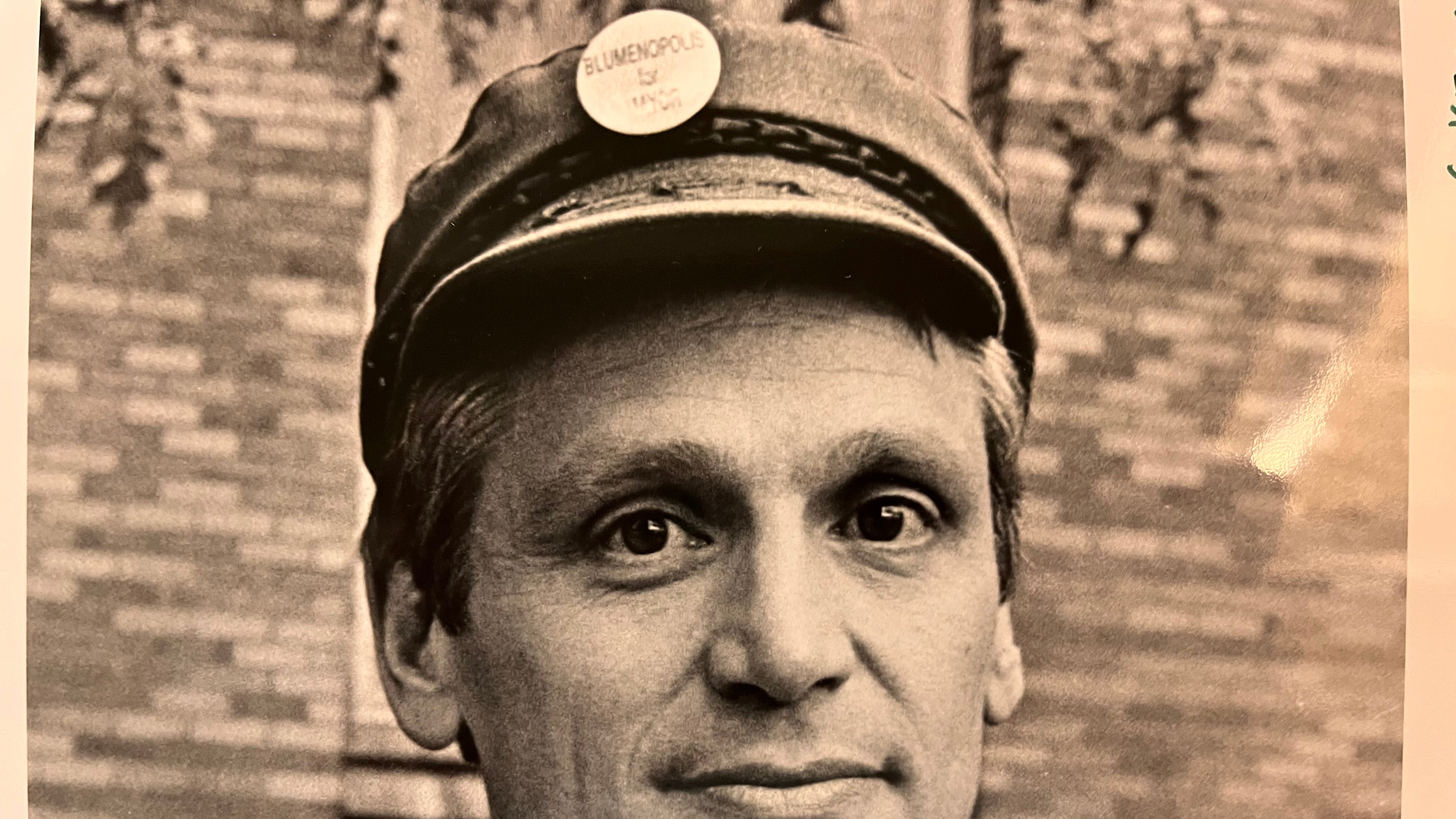

A week ago Monday, U.S. Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-Ore.) announced the impending close of a three-decade career in Congress. He was in a reflective mood, by turns defensive and critical of his legacy of public service. He also expressed revulsion at the idea of returning to Portland City Hall. Blumenauer remained, as always, a singular and contradictory figure.

Perhaps the closest any reporter came to unlocking the mystery of Blumenauer’s personality was Rachel Zimmerman in 1992, when Blumenauer was running for mayor in a close contest against Vera Katz. (He lost that race, and soon set his eyes on Washington, D.C.) In her profile, Zimmerman tried to reconcile Blumenauer’s public success and personal tragedies—and asked what kind of elected official those experiences had produced.

This story first appeared in the Oct. 8, 1992, edition of WW.

Content note: It contains an extended discussion of suicide.

Suddenly and without warning a sheet of snow fell from the sky over Broken Top, blanketing a small meadow high above the timberline.

It was the winter of 1974, and Earl Blumenauer and Robert Frisbee, hiking partners and political soulmates, sat on the Central Oregon mountain, playing chess while a blizzard unfolded around them.

Finally Frisbee, cold and uncomfortable, had enough: “I said to him, Earl, let’s stop, we should go find camp.”

But Blumenauer, huddled over the board, shook his head: No, the match was just getting interesting.

“He insisted that we sit there in the storm for an hour and finish,” Frisbee said. “He won.”

Earl Blumenauer, the wunderkind of local government, has never let a mere storm—atmospheric, emotional or political—hold him back. In 1974, he possessed a relentless drive to complete a task as well as an apparent lack of concern for the needs of others. Eighteen years later, this tension remains.

A master mechanic of the political process who was swept into public life at the tender age of 20, Blumenauer is endowed with an unflappable ability to tackle complex problems and emerge with clear solutions. Now, at age 44, Blumenauer has his sights set on becoming mayor of the 27th-largest city in the United States.

Polls indicate that Blumenauer is trailing his opponent, state Rep. Vera Katz. A loss would be a profound disappointment to Blumenauer, though some say that he would still wield tremendous power in Portland’s commissioner form of city government. Even if he lost, Blumenauer would keep his seat on the City Council. Moreover, he has a loyal ally in Commissioner Gretchen Kafoury and likely support from Charlie Hales, who is favored to take the seat now held by outgoing Commissioner Dick Bogle. With this three-vote bloc, Blumenauer would remain a force to be reckoned with.

All of which begs the question: Just who is Earl Blumenauer? In an age when voters are more often familiar with a candidate’s style than with his substance, Blumenauer turns the equation on its head. Most Portlanders know that, on the issues, Blumenauer is, like Katz, a progressive liberal. What puzzles voters is Blumenauer’s style.

Katz is effusive while Blumenauer is efficient. She is bubbly and emotive and loves to work a crowd; he is reticent and private, irked by the public glare. Katz is a New Yorker who never learned to drive. Blumenauer is a Portland native, compulsively driven. This difference in approaches, more than anything else, accounts for last May’s primary results: Katz received 47 percent of the vote to Blumenauer’s 35 percent.

Words such as “arrogant,” “cold” and “controlling” are often used to describe Blumenauer by those he has bruised. But in dozens of interviews with friends, family and colleagues, Blumenauer comes across as a more sympathetic character His emotional distance shields an upbringing of unusual pain, a past that Blumenauer vigorously guards.

Blumenauer’s struggle to overcome his inherently shy nature makes his achievements in government even more admirable—and his political dilemma all the more poignant. For Blumenauer’s problem is not one of vision. He has a razor-sharp image of where he wants to lead Portland. Rather, Blumenauer’s difficulty is more complex. He has yet to realize that coming to grips with one’s frailties, to embrace one’s private history, has become a political necessity.

From the moment 20-year-old Earl Blumenauer forked over his first $5 campaign contribution—to Eugene McCarthy in 1968—he was hopelessly smitten with the world of politics.

Even before that, as a member of Centennial High School’s debate team and second vice president on the student council, Blumenauer was destined for a political path, friends said.

“He was one of my more memorable students,” said Glenn Lamb, Blumenauer’s debate coach from 1965 to ‘66 during his junior and senior years. “Very bright and very intense. He wasn’t one to sit around and waste time on small talk.”

Indeed, by 1967 he had married his high school sweetheart, Pamela Shelly, who had been voted Centennial’s Girl of the Year in 1966. The following year the couple had their first child, Jon. They were both 19.

By that time Blumenauer was majoring in political science at Lewis & Clark College. In 1970, his senior year, he led an initiative campaign that sought to reduce the voting age from 21 to 19.

Blumenauer’s campaign, called Go 19, mobilized undergraduates from Ashland lo Astoria and succeeded in gathering enough signatures to place the measure on the ballot in the spring of 1970.

Though Go 19 was defeated by voters, Blumenauer’s efforts did not go unnoticed. In 1971, he was asked to testify at a U.S. Senate subcommittee hearing on the federal effort to lower the voting age.

Adam Davis, a pollster who worked on Go 19 with Blumenauer, said the young organizer’s ability to lead a such a disparate group of students and activists was uncanny.

“He was politically astute at a very early age,” Davis said.

In Blumenauer’s youth, he had been drawn to fundamental Christianity because, he said, “they seemed to have the answers—everything was black and white.” As an adult, his faith shifted to politics.

Shortly after his U.S. Senate appearance, Blumenauer was recruited by New York Congressman Allard Lowenstein to work in Oregon on his Register for Peace campaign, a nationwide voter registration drive. During a brief trip to Lowenstein’s home in Long Island, Blumenauer recalled, he was sitting in the back seat of the congressman’s car, awed by a passionate discussion about the Vietnam War between Lowenstein and Barney Frank, now a U.S. representative from Massachusetts. “I remember thinking it all seemed terribly important,” Blumenauer said.

After two years as assistant to the president of Portland Slate University from 1970 to 1972, Blumenauer succumbed to the urging of Ron Buel, then-campaign manager to Neil Goldschmidt and later founder of Willamette Week, to run for the Oregon Legislature. Democrat Blumenauer was elected to represent House District 11 in Southeast Portland at 21, making him the youngest legislator in state history.

He was one of the baby-faced young turks that were voted into office in 1971, a group that included Vera Katz, Rick Gustafson, Steven Kafoury and Les AuCoin.

When he arrived in Salem, Blumenauer found himself surrounded by lawyers with the technical knowledge that he felt made them better equipped to legislate. Blumenauer took the law school entry exam, scored high and was admitted to Lewis & Clark’s Northwestern School of Law, which he attended at night and between legislative sessions. He received his law degree in 1976 but has never taken the bar exam. “Someday,” Blumenauer said, “when I have six weeks, I’ll do it.”

Blumenauer made a name for himself during his six years in Salem, as a brash and radical lawmaker, a recycling enthusiast on the cutting edge of environmental and land use reform. His appearance on the House floor wearing sandals is remembered still.

In his final term he lobbied to amend a civil rights bill to include sexual orientation in addition to race, religion and gender. But gay rights were still uncharted territory for Oregon legislators in the 1970s, and the progressives were outnumbered. The bill died in committee.

Blumenauer left Salem in 1978 and headed home, running successfully against Republican Rex Snook for a seat on the Multnomah County Board of Commissioners. “I enjoyed the local government issues, and I wanted to do something full time,” Blumenauer said, explaining his departure from the Legislature. “I also wanted to be closer to my family.”

Pamela Shelly, Blumenauer’s wife at the time, remembered his years in the Legislature as a tornado of political activity with Earl never stopping for a moment’s rest.

“He spent all of his time, all of his money on politics,” Shelly said. “Sometimes I’d get jealous—maybe jealous isn’t quite the right word. I wish he’d given as much time to the relationship as he did to politics.” The two divorced in 1974, one year after the birth of their second child, Annie.

Growing more fiscally conservative during his eight years on the county commission, Blumenauer focused on streamlining city and county functions. He sought to consolidate social services at the county level, moving such operations as roads, parks and fire protection to the city. He created night court for county citizens and secured funds for a 911 emergency line. He also introduced a cooperative day care program for county employees.

“His leadership began to be evident on the county commission,” said Don Frisbee, chairman of PacifiCorp, Robert’s father and Blumenauer’s mentor. “Up until that time, specific issues were more important to Earl. But in the county he learned the importance of coalition building.”

Frisbee says he has always been struck by Blumenauer’s levelheaded pragmatism. “He never had any false hopes or dreams,” Frisbee said. “His ideas are all doable, not ones that you need a bolt of lightning to make happen.”

Blumenauer’s greatest political loss came in 1981, when he ran for an open seat on the Portland City Council. In the special election March 31, Blumenauer lost the seat to a political newcomer, grass-roots activist Margaret Strachan, by 10,000 votes.

“He got beat by this woman from out of nowhere, a neophyte,” said Carol Kelsey, a longtime political consultant. “It was the first time Earl really ever lost. He went into a severe depression.”

Pam Shelly blamed the loss on a news story revealing political favors granted to Blumenauer by lobbyist and ex-con Bobby Harris.

The Blumenauers had spent a weekend at Harris’ Hawaiian condominium on Molokai in the late 1970s, and though they paid for the vacation by check, Harris reportedly never cashed it.

“I was the one who wanted to go to Hawaii,” Shelly said in a recent interview. “I remember writing the check. He never cashed it, and the story cost Earl the election.”

Five years later, Blumenauer easily won in an uncontested race for outgoing Commissioner Mildred Schwab’s seat on the Portland City Council.

From the moment he took official City Hall, Blumenauer has been a whirling dervish among bureaucrats, his days beginning at 5:10 am and running well into the evening. As the city commissioner in charge of the Bureau of Environmental Services and the Department of Transportation, Blumenauer’s accomplishments range from an overhaul of the mid-county sewer system to a ban on polystyrene foam to the franchising of trash collection. Unafraid to take a less than popular stand. Blumenauer single-handedly killed a $130 million plan to move an eastbank section of Interstate 5 and build a waterfront park because he thought it would impede the funding of regional light rail. In another controversial move, Blumenauer supported efforts to raze four Northwest Victorian homes to build a row-house development, stating that the need for urban density overshadowed residents’ romantic concerns for landmark preservation.

“He’s focused, he’s clear, he knows how to get things done,” said Gretchen Kafoury, who served with Blumenauer at the county before joining him on the City Council in 1990. Though Kafoury’s ties to Vera Katz are deep—they both worked on Bobby Kennedy’s presidential campaign and later picketed outside the men-only City Club in the ‘70s to open the club’s doors to women—she is backing Blumenauer for mayor. “Everyone asks me why I’m supporting a man over a woman,” Kafoury said. “And if it were anybody else in the city running, I’d be supporting Vera.”

She points out that Blumenauer’s record on women and minorities hiring outshines all other commissioners’ in the city.

“Earl is the best politician I know,” said his ex-wife, still one of his most loyal supporters. “He popped out of his mother’s womb wanting to serve.”

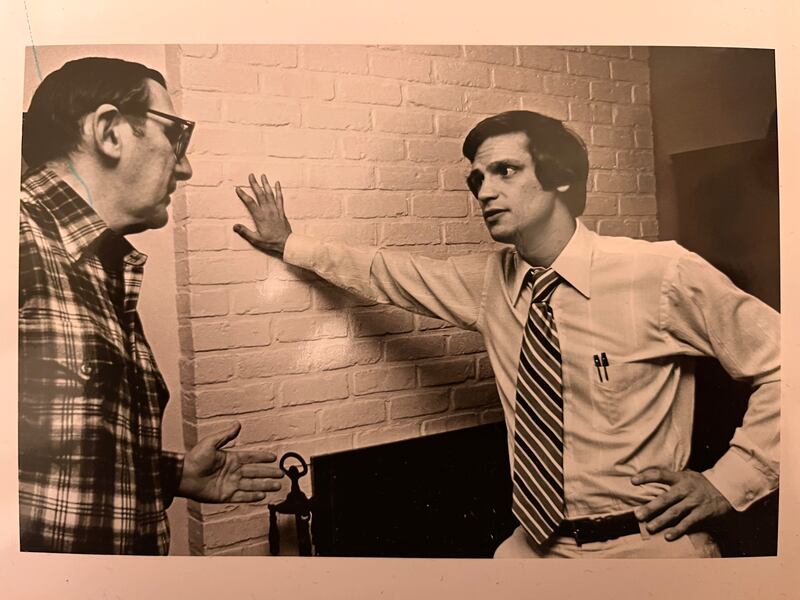

With these glowing endorsements, it is easy to see why some view Blumenauer as the most qualified mayoral candidate in recent history. At the same time, there is the issue of his style, which has been characterized as brusque and cerebral: Some say Blumenauer’s unyielding tunnel vision has prevented a good elected official from becoming a great one.

Though supporters maintain that Blumenauer’s nuts-and-bolts drive is a much-needed antidote to eight years of Bud Clark, detractors spin myriad stories casting Blumenauer as a technocrat, devoid of compassion.

“I’ll never forget his very first staff meeting in 1986,” said Darr Durham, who is married to Ron Buel and worked for Blumenauer in the Planning Bureau until the division was taken over by Kafoury last year. “He came in and told everyone to take a good long look around the table because all of us wouldn’t be there this time next year. It’s an odd way to build camaraderie. I wouldn’t vote for him for dog catcher.”

And local lawyer Chuck Duffy, who worked for Mayor Bud Clark, has gone out of his way to condemn the prospect of Blumenauer as mayor.

“From Ed Koch in New York and Harold Washington of Chicago,” Duffy wrote in a column in Northwest Neighbor, “to mayors of small towns in Nebraska and Arkansas, they all share one characteristic. They care and they listen…. Earl Blumenauer not only disdains listening to citizens, he is, in my opinion, incapable of doing it.”

One City Hall insider praised Blumenauer’s intellect and energy but said he has been known to be hurtful and abrasive in pursuing his own agenda. “Portland is still a small town,” the source said. “People still talk to each other here, and on some level human relationships still matter.”

What those who distrust him don’t know is that Earl Blumenauer’s enigmatic distance, his wall of silence, is largely impenetrable and perhaps unconscious because he is trying to steer clear of a past as dark and harrowing as a child’s worst nightmare.

Though friends won’t disclose many details, everyone agrees Earl grew up in what professionals would call a dysfunctional family. For one thing, Raymond W. Blumenauer, Earl’s father, had a drinking problem. A heavy equipment operator at Sears who divorced Earl’s mother twice, Ray disappeared on several occasions while his two sons were growing up on Franklin Street in Southeast Portland and later on Northeast 73rd Avenue. At a very young age, Earl took responsibility for the care of his mother, Ruth, who was frequently ill, and his brother Allen Scott, five years his junior.

After one long disappearance, Ray Blumenauer surfaced in Anchorage, Alaska, where he spent his days battling emphysema and alcoholism.

Then, in the mid 1970s, Ray Blumenauer reappeared in Portland.

“One day he just showed up on Earl’s doorstep,” said Janice Babcock, Blumenauer’s second wife since 1989. “And he didn’t come home to make peace with his son. Pam and Earl took care of him for months. Then he died.”

Blumenauer refuses to discuss his father or their relationship, stating only: “We are all a product of a complex set of experiences—genetic codes, luck and who knows what else.”

But Babcock says the issues surrounding his upbringing are too traumatic for Blumenauer to handle. “He doesn’t talk about it,” she said bluntly. “It’s just too painful.”

Donna Montee, Blumenauer’s legislative secretary at the time, recalls the difficulty he had accepting the fact that his father was dying. “There’s a part of him that was in denial,” she said. “He didn’t want to admit it was happening.”

His father died Dec. 13, 1976. Two years later, Blumenauer was to experience a tragedy even more profound.

Allen Scott Blumenauer graduated from Centennial High School in 1972, but unlike his older brother Earl, Scott was not a player in school politics or extracurricular activities. He never joined a club or sports team. Beneath the photo in his yearbook, where other students are defined by their outside hobbies or academic honors, the only words listed are “Lynch Park,” Scott’s grade school, which no longer exists. Scott had his brother’s deep-set brown eyes, but he was taller, nearly 6 feet, with brown hair and a beard. Those who knew him said he served a short stint in the Navy and suffered from frequent bouts of depression.

In 1978, at the age of 25, Allen Scott Blumenauer left his home on Southeast 155th Avenue and was never seen again.

Days before, he had signed over the title to his yellow 1976 Fiat to his estranged wife, Debra. He also gave her a large sum of money. Shortly thereafter, he went to G. I. Joe’s and purchased a .357 caliber revolver and 49 rounds of ammunition.

Three years passed and no one heard from Scott. Then, on May 18, 1981, a local resident was scouring the forest east of Salmon River Road in Zigzag for firewood when he discovered a human skull and scattered bones. Amid the mulch and debris, detectives found Scott’s belongings: an empty wine bottle, a decomposed pack of Marlboros, eyeglasses and a red Scripto disposable lighter. His wallet, still intact, contained a driver’s license, a scuba diving certificate, a Mount Hood Community College ID card and $5.16. The revolver was buried under a layer of leaves.

Blumenauer’s skull bore linear fractures consistent with a gunshot wound. On May 20, State Deputy Medical Examiner Ronald O’Halioran ruled the death a suicide.

“I remember this one,” said State Trooper Brian Boyd, the first police officer to view the corpse, “because it was such an unusual suicide. Most [people who die of suicide], on some level, want to be found. They leave a note or some trace of something. This guy was like a cat—he never wanted to be found.”

In many ways, Allen Scott Blumenauer has not yet been found. The commissioner himself will shed no light on the subject. “I don’t think that’s particularly relevant to what I ‘m trying to do as mayor,” Blumenauer said. “I’m not interested in talking about it.”

The discovery of the body was never reported in the press. Even those close to Blumenauer are unaware of the circumstances surrounding Scott’s death. June Williamson, Blumenauer’s campaign manager and friend since 1973, said she never knew the details. Others were surprised to learn that Blumenauer ever had a brother.

Those who did know about it said Scott’s death was devastating for Blumenauer, another tragic event in a family history of struggles and loss.

“If there are issues that are so difficult and so deep that they have not been confronted and dealt with,” said a prominent Portland psychiatrist, “then you have to throw a blanket over everything. Emotions become restricted.”

Some suggest that Blumenauer’s unwillingness to confront his personal pain help to define a political style that is cold, distant and aloof.

“He wishes it didn’t inform his political life,” Janice Babcock said, adding that Blumenauer rarely broaches the subject of Scott’s suicide even with her, except to reminisce periodically about a cross country trek the brothers took years ago.

Even Blumenauer’s interests in government shy away from people in favor of process: He’d rather talk about land use planning than welfare reform, and his interest in curbside recycling surpasses any initiative to tackle the problem of homelessness. During the primary, WW asked Blumenauer how he would solve the twin problems of crime and lack of opportunity in North and Northeast Portland. Blumenauer suggested the construction of a light-rail line to Vancouver.

Blumenauer’s campaign is obviously aware of their candidate’s liabilities. “At times he is inaccessible,” Williamson conceded, “but he’s gotten a lot better.”

In fact, the entire thrust of the “Blumenauer for Mayor” campaign has been to gussy Earl up us a happy-go-lucky, regular kind of guy who happens to have a passion for government. At the urging of businessman Bill Naito, Blumenauer even agreed to don a bow tie.

In an effort to show Blumenauer with “the people,” the campaign crafted a Community Works Project, which has, despite its political timing, brought good deeds to neighborhoods, ranging from a food drive at Fish Emergency Service Center to a cleanup at a neighborhood youth shelter.

Since Sept. 1, the campaign has spent $15,000 solely on “People for Earl” ads in The Oregonian. And the final effort to recast a portrait of Earl comes in the form of oversized lawn signs bearing the commissioner’s dimpled countenance gazing up to the heavens.

The photographic image, taken from a television spot, looks like Earl’s just had an epiphany.

Blumenauer stares across a booth at McMenamins on Northeast 15th Avenue and Broadway, sipping a pint of Terminator. Still riding the endorphin high from his previous day running the Portland Marathon, he is animated, even excited. (It was an easy race, injury free, unlike in 1990, when he ran the New York Marathon with a broken rib and arm.)

Although Blumenauer is unwilling to talk about his personal tragedies, he readily shares his thoughts about “style.”

He is dismayed at “the People magazine approach to politics,” which he says twists and trivializes complexity into commodity, and invades the sacred world of the individual.

“It gets to the point where it strays too far from the nuts and bolts of how you try to work with people and solve problems,” Blumenauer said.

But simply being a problem solver is not enough to satisfy today’s leadership-starved electorate. As Bill Clinton comes to grips on national television with the pain of an alcoholic father and Al Gore chokes up while conjuring the horror of his son’s near-fatal car accident, Blumenauer is resolute in his belief that personal narratives have no place in the political sphere.

“What’s going on on the national level is a disgrace,” he said, characterizing the public gushing as manipulative and trite.

After two decades in public life, Blumenauer would prefer to exist solely in the world of his record. But as many politicians have discovered, the current styles of leadership are shifting; humanity, empathy and an ability to listen have become priorities. When economics sour and hatred suddenly erupts, voters feel betrayed and desperate for guidance: The rhetoric of public officials’ past accomplishments and powerful records is instantly eclipsed; the job of any leader becomes simply to resonate with healing and compassion.

If Blumenauer has a flaw, it may be his resistance to accept the fact that the personal informs the political. But somewhere in his soul is the knowledge that he must either adapt his style or find another mode in which to serve. An evolved Earl Blumenauer, with his keen sense of irony, respect for history and rich intelligence, could someday be a great and caring leader of this city—or of the state.

Some think he’s well on the way.

“As a friend, Earl Blumenauer is the most emotionally committed man I know,” said Robert Frisbee, who has looked on as Blumenauer transcended many a struggle. “If I called him up and said, ‘I need you to meet me at the Zanzibar airport tomorrow,’ and hung up, I know for a fact he’d be there.”