In one of the zaniest episodes in Street Scenes' enthralling production of Suzan-Lori Parks' Pulitzer Prize-winning play Topdog/Underdog, a man walks onstage and pulls a plethora of stolen clothes from beneath his bulky jacket. Belts, shoes, socks, ties and even two suits emerge from his coat, like someone yanking rabbits from the depths of a dark top hat.

That moment makes for an uproarious sight gag, but also provides a fitting metaphor for the play's narrative. A tale of two African-American brothers fighting about life, work and women, Topdog/Underdog is ostensibly a saga of sibling rivalry. Yet it is also about how resentments and traumatic memories fester in the minds of the two men, leading to a climax in which their inner torment bursts out with the force of an exploding grenade.

Which doesn't mean Topdog/Underdog is 100 percent serious. Rich in comedy, tragedy and magnificent, multifaceted performances, the play—directed by Bobby Bermea and Jamie M. Rea—is a full-course theatrical meal that doesn't simply entertain or disturb. It does both at the same time, leaving you haunted by an unnerving conclusion and delighted by the journey that brought you there.

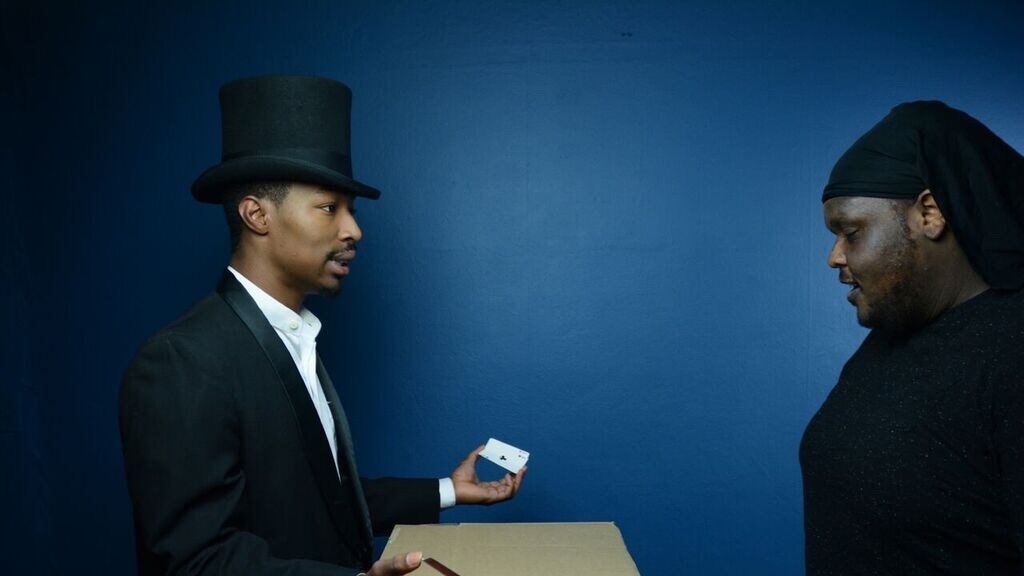

The brothers on the journey in question are Lincoln (La'Tevin Alexander) and Booth (Curtis Maxey Jr.), whose names are allegedly the product of their father's skewed sense of humor. The siblings, abandoned by their parents long ago, are witty and charismatic. Yet their circumstances worsen as the story progresses. Booth is unemployed, and while Lincoln has a job—he dons white makeup and a fake beard to play the more famous Lincoln at an arcade—his boss is eager to replace him with a dummy.

An exhilarating intimacy pervades Booth and Lincoln's universe. The entire narrative is confined to Booth's home—where Lincoln has moved after his wife, Cookie, left him—and we never meet any of the significant others or family members that the brothers allude to. Most of the play—including a goofy yet poignant scene in which Booth fashions a dinner table out of milk crates so he and Lincoln can eat Chinese food together—has a loose, casual vibe that makes us feel as if we're sharing their lives rather than simply watching them unfold.

What makes the play powerful, though, is the way Alexander and Maxey Jr. show us the anguish that simmers beneath their characters' toughened exteriors. When Lincoln turns a game of three-card monte into a display of furious machismo, Alexander demonstrates the hunger for confidence and control behind Lincoln's modesty. And when Booth's joking demeanor dissipates into violent, infantile rage at play's end, Maxey Jr. delivers a performance that makes you both pity Booth and fear for him and everyone in his life.

Booth's outburst sets the stage for the play's fearsome finale, which adds brutality to a story that, until then, has consisted mainly of two guys talking. Yet Bermea, Rea and their peerless crew refuse to let the rising intensity overcome the characters or their emotions. Aided by Serah Pope's brilliantly subtle lighting design, they draw our attention not to the brutality that erupts, but to Booth's tears, each of which falls like a miniature hailstone.

It has been more than 17 years since Topdog/Underdog debuted, but the play's resonance hasn't dimmed in the slightest—there is a timeless, mythological power to the story of two brothers bound together by equal parts love and jealousy. Street Scenes has brought that story to brilliant life, ensuring that even when Topdog/Underdog is at its most harrowing, you won't turn away. You become transfixed.

SEE IT: Topdog/Underdog plays at Chapel Theatre, 4107 SE Harrison St., Milwaukie, chapeltheatremilwaukie.com. 7:30 pm Thursday-Saturday and 5 pm Sunday, Nov. 24-Dec. 1. $20-$30.