Before exploring virtual realities, Myles de Bastion had dedicated his artistic life to the deaf and hard of hearing. The deaf Portland musician, designer and inventor had pioneered technologies translating live music into light and vibrations—featured everywhere from the Portland Art Museum to Jimmy Kimmel Live.

When COVID-19 forced people to insulate themselves in their own little worlds, de Bastion and the deaf community were faced with a discouraging question: Were those little worlds any more accessible than the average office or music venue? Often, no. Zoom, for instance, took well over a year to add auto-captioning technology. De Bastion says ubiquitous video-conferencing "solutions" also flattened, shrank and disrupted the spatial context needed to converse in sign language.

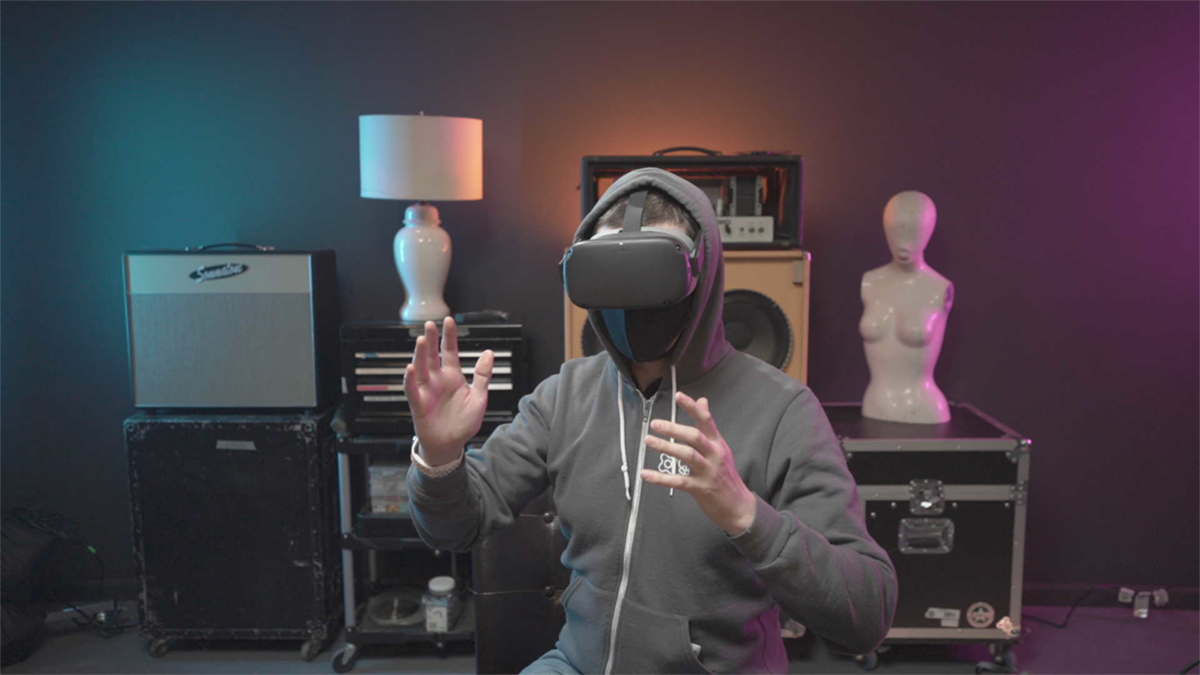

Amid these changes, though, virtual reality began dominating de Bastion's attention and became the centerpiece of his New Media Fellowship from Portland media center and nonprofit Open Signal. VR was a new medium—full of its own promise and pitfalls—to which he could apply his mission as a "creative altruist."

"As soon as I saw that hand-tracking support was coming to VR, I had visions of using it to communicate with other VR users," de Bastion says. "In a Zoom meeting you don't have any sense of physical space, so you lose a lot of the ability to communicate [in American Sign Language] fluently, and conversations take much longer. VR solves this by restoring the sense of physical space that is needed for ASL."

On March 19, de Bastion presented the fruits of his labor to Open Signal's online audience, titled Virtual Worlds Made Accessible Beyond Sound, demonstrating innovative plans for VR captioning and communication methods.

"[VR] is work. It's play. It's social. But it's not accessible," de Bastion said to a live audience on Facebook and YouTube.

The artist's capstone demonstration hinged mostly on two conversing robots: a simple scenario in VR, but prohibitively limiting to deaf and hard-of-hearing users. Traditional closed captioning, for example, does precious little to clarify who is speaking when navigating a three-dimensional space. Furthermore, VR captioning doesn't currently respond to the direction of a user's gaze at a given moment.

The first potential solution is a feature de Bastion calls "environmental captioning," addressing the need for clarity and speech attribution as a user explores 360 degrees. In de Bastion's demo, dialogue appears physically linked to the VR avatars without obscuring them. Then, there's the potential for dialogue coloring, directional arrows, and perhaps shifting text opacity when a user looks elsewhere or approaches from a distance.

Sign language input constitutes de Bastion's second area of emphasis. The Oculus headset's current inability to clearly display overlapping hands and their positions in space is still a hurdle.

Then, there are the human obstacles. Proposed accessibility measures may seem like no-brainers to VR outsiders or neophytes watching de Bastion's presentation, but their implementation faces obstinate designers and slow-moving corporations alike.

"I always get resistance from other [user-experience] designers when I propose that VR support ASL as a mode of data input," de Bastion says.

He points to one of his recent Twitter threads where a commenting designer even prized Morse code over ASL for language inputting. Ignorance and insensitivity disguised as practical arguments stand in the way, as does the financial incentive for mammoth corporations. Still, de Bastion insists he's making headway.

"It is still early days, but my involvement with the WC3 XR Captioning Workgroup has started to open doors and important conversations with stakeholders at some of the big tech companies," he says. "I have yet to see any of them make a serious commitment (allocation of resources) to creative inclusive VR access initiatives."

De Bastion plans to further pursue his vision by building open source plug-in tools that won't leave accessibility up to other engineers' lines of code. Even if the larger VR field still appears in its infancy, he says issues of who can use it freely will factor centrally into his forthcoming work and everyone's ability to communicate within it effectively.

"I believe VR is the future for how we will work, play and socialize," de Bastion says, "and it is just a matter of the technology becoming comfortable and accessible enough to benefit everyone."

SEE IT: Virtual Worlds Made Accessible Beyond Sound streams at watch.opensignalpdx.org/live. Free.