Depending who you asked, the recently deceased publisher Adam Parfrey was a champion of the First Amendment, a misogynist who enabled white supremacists, or just very sick in the head.

But for a time, he made Portland a capital of outsider publishing—and in 1998, used this city as a launch pad for Feral House, which soon became the nation's top imprint for taboo books.

He published a novel by Joseph Goebbels, the writings of Charles Manson and the manifesto of Timothy McVeigh. At the same time, he became a darling of Portland's underground literary scene, where provocation and freakishness were badges of honor.

Parfrey died May 10 in Port Townsend, Wash., on the Olympic Peninsula. He was 61 and had suffered a series of strokes.

He died before the world ended, which would have come as a surprise to him.

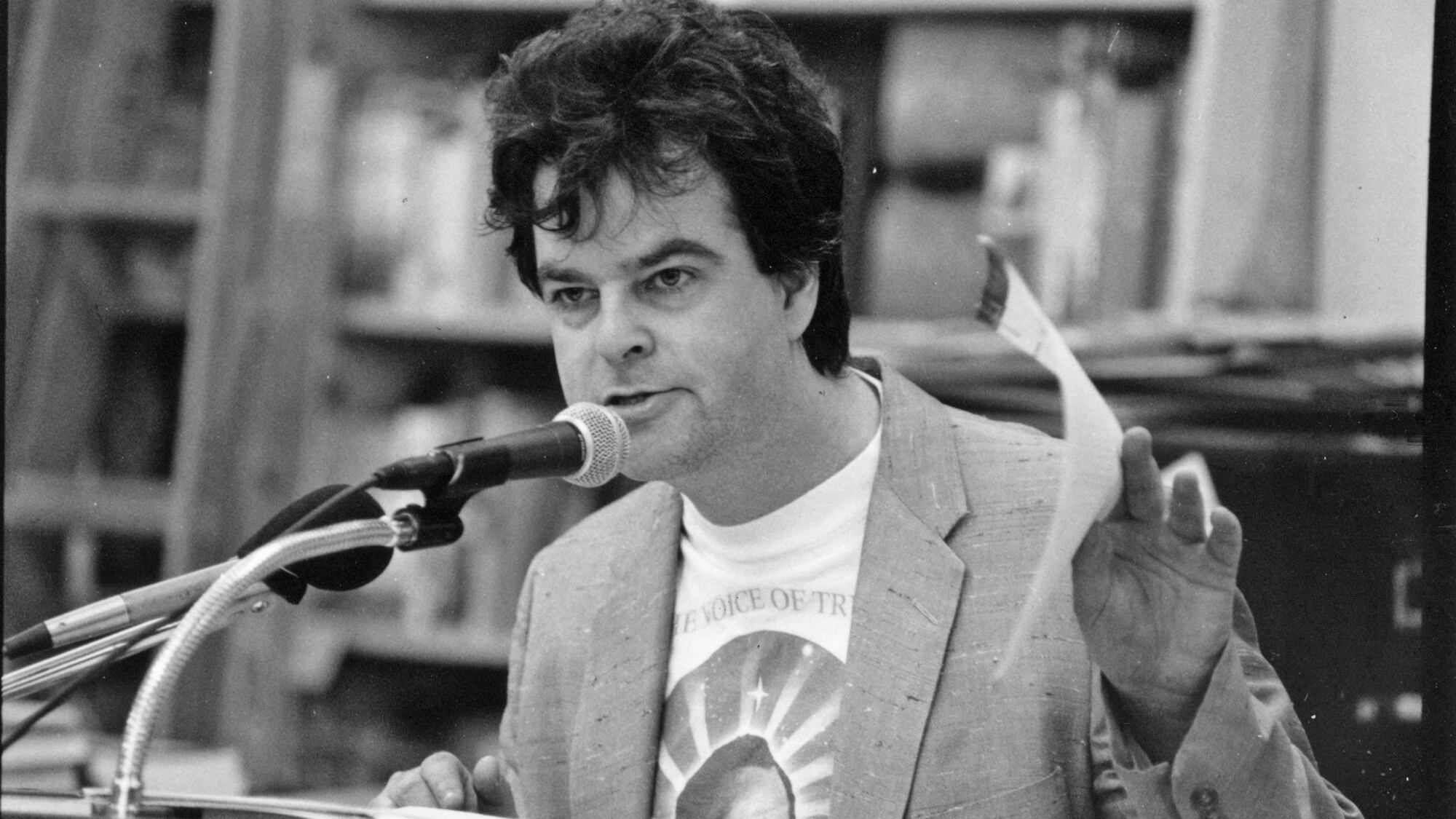

"I think the world's going mad," he told WW during a Powell's appearance in 1992. He added his prescription for saving the planet: "Murder as many people as possible. It's not the culture, it's nature that's worth saving."

Showing that modern culture was hopelessly debased and perverse was Parfrey's guiding principle in publishing (along with taunting anyone who dared take offense, which seemed like an equal motivation).

His defining works were Apocalypse Culture, published in 1987, and Apocalypse Culture II, which followed in 2000.

The first book contained chapters on necrophilia and secret societies, as well as a section titled, "Cut It Off: A Case for Self-Castration." The second included actor Crispin Glover weighing the usefulness of murdering Steven Spielberg and an interview with the founder (and lone member) of Jews for Hitler.

"It was a mix of really wacko conspiracy theories, the occult, and not just countercultures but subcultures," recalls Portland Tribune reporter Jim Redden, who first encountered Parfrey in 1992, while Redden was publishing the newspaper PDXS. "But I think at that time, people wanted to be shocked. The audience was there for the stuff he was publishing. The audience wanted to be shocked—or prove it was too hip to be shocked."

Parfrey found an audience and a scene in Portland—he moved here briefly in 1988, long enough to found Feral House, then came back for a longer stay from 1992 to about 1999.

He then moved to Los Angeles, and eventually Washington state. Feral House remained a going enterprise until his death last week.

To look at clips from Parfey's heyday is to get a whiff of Portland's grimy 1980s literary underground—a place where Jim Rose's circus freaks mixed with writers getting book deals. It's also easy to spot precursors to our current culture wars and backlash movements.

The riptides of resentment that led Portland writers like Chuck Palahniuk of Fight Club fame and Jim Goad, author of Redneck Manifesto, to the embrace of men's-rights fringe groups were present in Parfrey, too. (He published several of Goad's books.) Like those authors, Parfrey delighted in taunting censorious enemies—especially feminist women.

Related: The far right's strange obsession with Chuck Palahniuk.

In 1992, WW attended Parfrey's reading at Powell's Books, where the author spent much of him time lampooning feminists trying to pass a bill in the Oregon Legislature that would have allowed victims of sexual violence to sue the publishers of pornographic materials that might have inspired the crimes.

"Parfrey's cause is freedom of expression and the defense of the First Amendment from attacks launched by the religious right and the feminist left," WW critic Audrey VanBuskirk wrote. "Parfrey's appearance at Powell's had the uneasy energy of a meeting for a revolutionary group that hadn't quite found its cause. The chairs were filled with mostly black-garbed, mostly male sympathizers (including our city's resident Satanist, the diminutive Rex Diablos Church), who chuckled unpleasantly at his easy feminist-bashing."

But what set Parfrey apart was his dedication not just to shock value and provocation but to the real real extremes in American life: militia men, sex fiends, devil worshipers and race warriors.

His commitment to free speech was unsettling in part because he wanted to expose readers to horrifying ideas in their raw form. Was that because he wanted to expose those beliefs, or because he shared them? He wasn't saying. But he was taking people places they still don't want to go.

"It seems like an awful lot of people grow goatees and talk about hip things," Parfrey told WW in 2000 upon the publication of Apocalypse Culture II. "But with this book, if you think it's all hip and kind and wonderful and groovy—well, there are some things in this book that are not very groovy at all. You have to look at it and figure out, what does free speech mean? What do these terrible things mean? We live in a world where some not very hip things are happening, and this book tries to get at some of them."