If you are very good and very lucky, you will live beneath the notice of national political pundits. Oregon has been bad.

Last month, for the second time in four years, the roving eye of the national media was drawn here by an armed rural insurrection. You know the story: Republican senators left the state to block a cap on carbon emissions. One of their number intimated he would shoot any cop who pursued him. Militia groups offered to loan him their marksmen—and were rebuffed.

National audiences know the wrong story. It was described to them as a right-wing coup by online aggregators and television talking heads who are incentivized by attention and unchecked by any consequences for getting the tale wrong. This environment makes the pundits exceptionally confident and stupid.

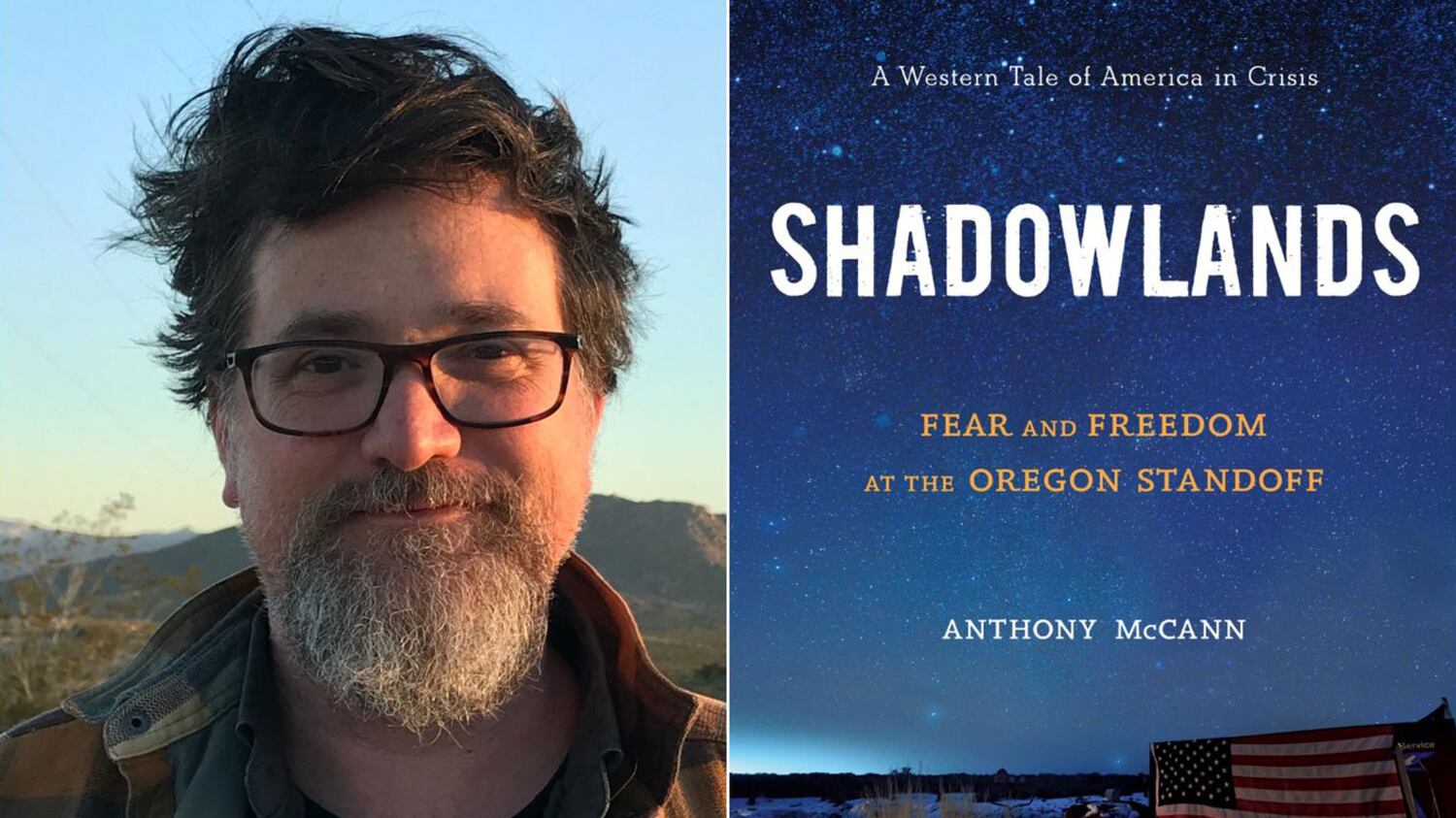

Oregon journalists have been whining about this since 2016, when a second-generation sagebrush rebel named Ammon Bundy seized a bird refuge in the name of cattle-grazing rights and abolishing federal land ownership. (You'll recall there was a killing, and a federal trial.) Now here comes another interloper, Anthony McCann, a Mojave Desert writer who has published a book on the occupation, Shadowlands: Fear and Freedom at the Oregon Standoff (Bloomsbury, 423 pages, $30).

Related: Bundyland: Two devout Mormon brothers have created a fantasy camp for commandos in Eastern Oregon.

It is a happier marriage of author and subject. McCann is a poet—like, he publishes volumes of poetry—and his book is not a history but a reported essay. He doesn't want to be recognized as an expert on the Bundys—he wants to drive into the high desert and think about what it all meant.

In a way, this is a more difficult ambition. It could go wrong in so many ways, all of them ponderous. There are pages of Shadowlands in which this threatens to happen. (It was astute of McCann to notice that the refuge's name, Malheur, is French for "hard luck"; mentioning it just once would have sufficed.) But the book works more often than not—and when it does, it's fantastic.

McCann has a knack for quicksilver insights. He spots a telling detail and places it in contexts so unexpected readers have to question whether they'd grasped the Malheur story at all. The book is driven by a cross-ideological empathy: McCann is the first writer who has successfully translated Ammon Bundy's personal appeal, the "earnestness and openness of expression and care to Ammon's face" that made some ranchers trust his bizarre constitutional theories.

In the book's most powerful meditation, McCann considers the conspiracy theories that sprouted in Oregon's Harney County. McCann is not afraid to identify lies, or to pinpoint racist lies. But he recognizes the appeal of fake news—the comfort of believing you've been screwed over rather than left behind.

"Better that," he writes, "than to accept that the contemporary world and its globalized economy have no real interest at all in the Bundys—nor much use for so many of the people who would come to see themselves reflected in their struggle. Better to be wanted badly than not wanted at all."

It is a relief to read this book, to think rather than tweet, to acknowledge that your political enemy is also motivated by longing and loss. But why trust me? I'm a newspaperman in a town everybody knows is run by Antifa now.

SEE IT: Anthony McCann converses with Leah Sottile at Powell's City of Books, 1005 W Burnside St., powells.com, on Tuesday, July 9. 7:30 pm.