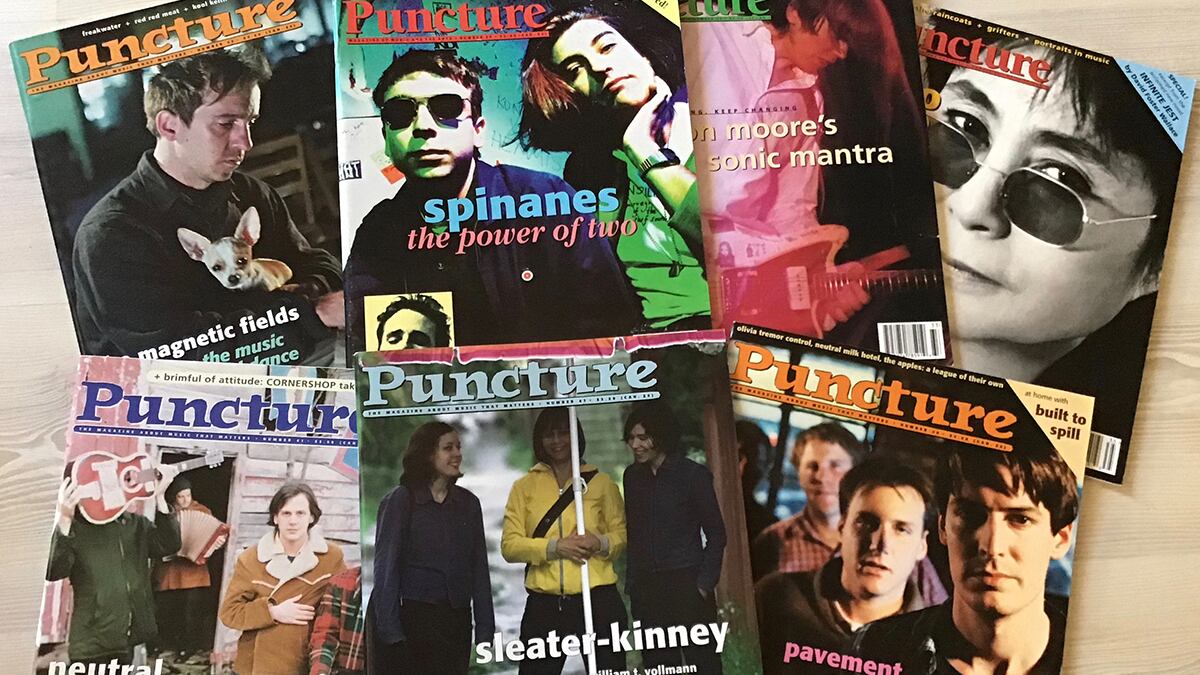

On the outside, the first issues of Puncture looked like the dozens of other roughly constructed zines covering punk and post-punk culture in the 1980s: hand-folded and stapled with cut-and-paste cover art.

What set it apart was the content on the inside. The writing was wise and witty, covering artists ignored by most other underground papers—the Virgin Prunes, Negativland, Toiling Midgets—and included thoughtful writing on literature and film. As it became a proper magazine with glossy covers, eventually relocating from San Francisco to Portland, and opened its ears to embrace hip-hop, jazz and the avant-garde, Puncture remained on the bleeding edge. It was the first to write about Guided By Voices, Jeff Buckley, and Neutral Milk Hotel in any meaningful way, and even published an early excerpt of David Foster Wallace's Infinite Jest before the novel became a phenomenon.

The magazine folded in 2000 when founder Katherine Spielmann and fellow editor-life partner Steve Connell started the publishing imprint Verse Chorus Press. But Puncture hasn't disappeared. The first six issues were anthologized last year, and this month sees the publication of Now Is The Time To Invent!, a collection of features culled from the magazine.

The book picks up the story in 1986—starting with college-rock luminaries Throwing Muses and ending with Sleater-Kinney, the cover stars of the final issue. In between are rare interviews with Fugazi and critic Lester Bangs, powerful essays on misogyny in the underground scene, and coverage of the now legendary 1991 International Pop Underground Convention in Olympia, Wash. It's not the complete story of Puncture but a great document of how indie went from a subgenre to a cultural watchword. The book also serves as a beautiful memorial to Spielmann, who passed away in 2016.

From his home in Hamburg, Germany, Connell spoke with WW about how he went from a reader to becoming the magazine's managing editor, covering the music no one else would, and watching those once-obscure artists become icons.

WW: When you stumbled upon Puncture, what made it stand out to you?

Steve Connell: There were some great fanzines, but they weren't as well written. Puncture had a frame of reference that the others didn't have. It seemed zine-y and punky but also very literate. And that's where I was. I was a weird university post-graduate who ended up working for Rough Trade. It was pretty clearly my kind of thing.

You moved to the U.S. to work at Rough Trade's offices in San Francisco not long after. Did you seek out Katherine immediately?

No. She called up the office because she was looking for a Test Dept record. We used to import all these English things and she had her ear to the ground. I was the person she ended up talking to, and I went, "Oh, Puncture! We should talk."

Clearly, you two hit it off instantly. What was it that drew you to Katherine?

We had a similar background in some ways. The first major discussion we had was about what was the best rock novel. Back then, there really weren't that many, and we agreed it was Don DeLillo's Great Jones Street. That was a good start, I think.

Even as the magazine got bigger, Puncture still stuck to covering artists and scenes that other publications tended to ignore.

We were definitely drawn to the more left-field stuff. I mean, I was a huge R.E.M. fan all through those years, but there wasn't much point raving about R.E.M. in a little zine when they were being covered in Rolling Stone.

Why did you move yourselves and the magazine to Portland?

I stopped working for Rough Trade, and then the [1989] earthquake happened, so Katherine didn't want to live in San Francisco anymore. And the city was changing pretty fast—it was yuppie-fying and rents were going up. We realized that if we wanted to spend more time doing Puncture and not have full-time jobs, we'd have to find a cheaper place to live. And, of course, in '92, when we moved, the scene with Hazel, Pond, and the Spinanes was starting to happen. We were like, "Yeah, this is the place to be."

Beyond music, Puncture was very connected to the world of literature, publishing excerpts of Infinite Jest and interviewing authors. Was that in the DNA of the magazine from the start?

I think Katherine probably would have most wanted to do a literary magazine. But there wasn't a DIY way to do that back then. We always wanted to make sure literature was in the mix. There were always reviews, and running excerpts of books started in the Portland years. And we transitioned into doing Verse Chorus Press and stopped doing Puncture.

How was it to experience the trajectory of Puncture from this photocopied, hand-stapled zine to a full-fledged magazine with a glossy cover?

We didn't want to fetishize this idea of, "It's gotta look like a zine." That was pretty much all you could do then. It was rubber cement, cut-and-paste, those guidelines that you cut with your X-Acto knife. We went with the technology as it developed. We got a Mac Plus as soon as they were available. I learned PageMaker and then it was off to the races.

Something that came out of the introductory essays in this collection was Katherine's pretty strict standards. How was it to have your work edited by her?

I probably got off more lightly than most people. It was really, really seriously done, professional work. Katherine worked for real magazines, so she didn't see any reason why it couldn't be presented that way, too. I think that's one thing that made it stand out. The major publications did that, but for a lot of the zines, it didn't necessarily matter that much. I think it made Puncture different in the end.

Was it gratifying to see artists that Puncture championed early on become more widely known?

It was fantastic to see all those bands get bigger, and they deserved it. Sleater-Kinney getting covered in Time magazine. Even the Mountain Goats—certainly the records are different and if [frontman John Darnielle] carried on recording into a boombox, it probably wouldn't have happened, but all the greatness was there in those songs. Maybe we played a little part in that, but I think it showed how things were changing, too. I remember Spin trashing Neutral Milk Hotel. At times it seemed like they didn't get or they didn't want to get it.

Puncture’s Greatest Hits

Women in Rock: An Open Letter

Writer Teri Sutton presaged the riot grrrl movement with her 1988 essay that lays bare the ugly sexism roiling within the supposedly enlightened indie-rock scene.

Sleater-Kinney

The first-ever interview with the venerated trio, with then-drummer Lora MacFarlane, was published in a 1995 issue of Puncture.

Fugazi

D.C.'s most important band gave a rare interview to Lois Maffeo in 1990 following the release of their first album, Repeater.

Jonathan Richman

Camden Joy blended fiction and journalism to wondrous effect for this portrait of the revered singer-songwriter.

The Pastels

In 1998, musician-poet David Berman interviewed the influential Scottish pop trio—by fax.

READ IT: Now Is the Time to Invent!: Reports From the Indie-Rock Revolution 1986-2000 is out now on Verse Chorus Press.