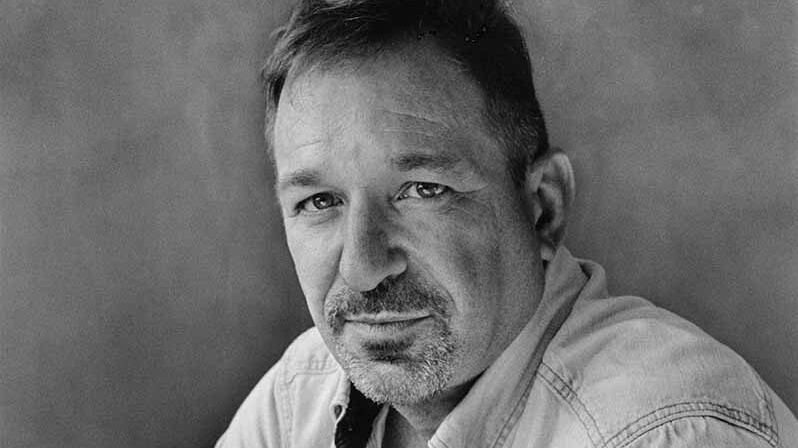

David Biespiel begins A Place of Exodus with a confession.

"I never told anyone this," he writes, "but for a time I thought I would be a rabbi when I grew up."

This is not his first memoir, or his first book––in fact, it is his 12th––but it is Biespiel's first effort to make something out of the spiritual arc of his childhood, a cinematic story of devotion, conflict and exile.

Before settling in Portland in 1995, Biespiel lived in eight states in nine years, searching for the meaning of home in each temporary city but unable to shake the first one: Meyerland, a predominantly Jewish neighborhood of Houston.

There, Biespiel describes speaking Hebrew with a Southern accent and living comfortably within every aspect of Jewish life and tradition.

Then a bout of intellectual rebellion in his teenage years led to a heated debate with a rabbi and a dramatic expulsion from Hebrew school.

Forty years later, Biespiel reflects on the subtleties of this time of his life, now with the confident lyricism of a writer who has spent the better part of his career as an award-winning poet. Today, Biespiel's time is spent as the founder of the Attic Institute of Arts and Letters, an independent writing studio in Southeast Portland, and as the first poet-in-residence at Oregon State University.

But pieces of Texas still work their way into his Pacific Northwestern routine, a constant reminder of the stubbornness of cultural roots.

"You can't get away from it," he says.

WW: Some authors feel called to publish deeply personal memoirs after full careers of writing about other things. Was this always a story you wanted to see published?

David Biespiel: I've been writing about this material in one iteration or another all along. The problem that I had when I was younger was that my emotions toward it were pretty hot. I couldn't cool down enough when I started to write to really get at the nuance I would have expected for myself. Now I'm older than the principal adults in the book, so that gave me some emotional leverage. I write in the book about going home and running into these old friends of mine, and them having this question: "David, where have you been?" as if I'd stepped out one night and didn't come back for 40 years. And that was another stimulant. That's where I found my question: Why didn't you go home? And the only way to answer that question was to dramatize why I left.

How did you want to write about Texas for a reader who might not be familiar with that reality?

As a friend of mine once said, "To say that Texas is a state with a reputation for being a home to Christians is like saying the Sahara is made up of sand." I'll say I'm from Texas, and people will say, "There are Jews from Texas?" In a state that is really identified with the Protestant roots of the American story, to talk about a gigantic minority Jewish community is a story people don't know. No one's at fault for that, it's just not a story that's been told.

One of the things you bring up in the first few pages is this idea that being a writer and being a rabbi both involve "purifying your principles." Did the process of writing this memoir feel theological?

By calling Texas "the place of Exodus" and blurring Texas and Judaism, I am calling my late 20th century American story another one of the stories of the children of Israel that came out of Egypt. In that way, it is theological. It's another version of events, bringing to life qualities that aren't present in the Old Testament.

For people who grow up in highly observant communities, there is this common experience of a crossroads where you either grow into or grow out of your faith. How did you want to convey that experience?

The quarrel with the rabbi—that was volcanic, and when you're writing about it, you have to go into it. I had to reinhabit my own thinking, my own arrogance, my own combativeness, and also portray his. It was a fight to the end. When I was rereading those parts to myself as I was working on them, I was hot. I felt that anger again. I felt both the triumph that I achieved and the shame. I feel like, for many people, it's hard to locate something in your life where you feel an experience as simultaneous triumph and shame.

You write about being a retired Jew, rather than a lapsed or an ex-believer. What were you hoping readers would get from this branding of identity?

I think of it as an ebb, a withdrawal, because Judaism isn't just a faith system. It's something you're born into. You can convert to the practice, but so much tension and commentary surrounds the idea of being born into it as a people. "Retired" conveys that I don't go to the office anymore. There's a boxing-in that goes into Judaism, where to practice Judaism is a Jewish act, to reject Judaism is a Jewish act, to swear never to return to Judaism is a Jewish act. No matter what you do, that's the most Jewish thing you can possibly do. The only way that I can think of linguistically to say that I'm outside of that paradigm is saying that I'm retired from that narrative.

Does it feel as though you have retired from Texas in the same way?

I miss that more. I don't miss the practice of religion, but I miss barbecue ribs on Saturday. A few years ago, I was on the Rio Grande writing a book. One day I went for a walk by myself down in Marfa, Texas, and I was trying to describe the sky to my wife because the sky in West Texas is enormous. You can see as far as the North Pole. The clouds are in motion and they're very low. And as I was describing this to my wife, she said, "You're coming home, right?" And I said, "Well, I am home. But I will be returning to Portland." I have a feeling for the place that is really underneath my skin.