Historians have devoted countless volumes to the United States’ wars on its Indigenous peoples. But few have touched on the wars waged on the Northern Paiutes who once roamed Eastern Oregon, and perhaps none has examined them from the Paiutes’ point of view—until now.

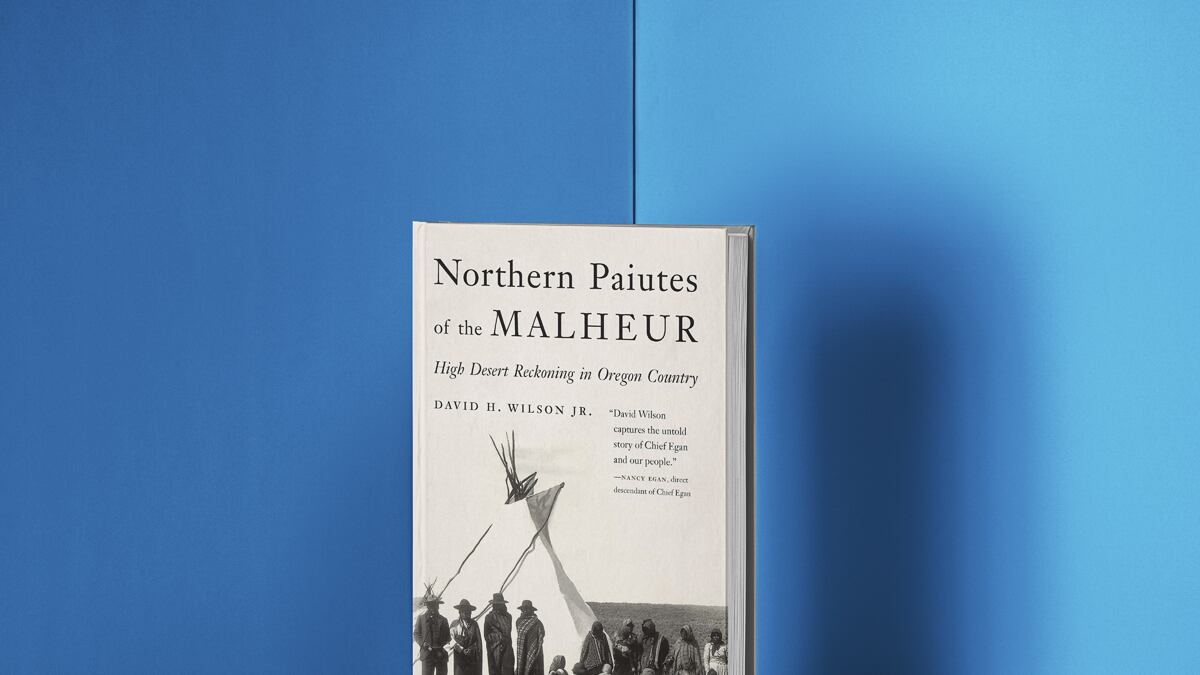

Portland author David H. Wilson Jr. spent eight years hiking and rafting Oregon’s high desert, meeting with descendants of the Paiutes, and researching primary sources to untangle the causes of a tragedy as infuriating in its own way as the Cherokee Trail of Tears. The result is a chronicle that deserves to be recognized as a definitive work of Native American history: Northern Paiutes of the Malheur: High Desert Reckoning in Oregon Country (Bison Books, 336 pages, $34.95).

Wilson meticulously picks apart the dubious claim, long accepted as fact by eminent historians, that Chief Egan of the Paiutes was the willing leader of the Bannock War of 1878 that raged through Eastern Oregon and Idaho and doomed the Paiutes to years of privation, exile and often death.

The claim that Egan was war chief makes no sense given Paiute history and culture, which Wilson lays out in rich detail: A nomadic people who foraged in small family groups for roots, seeds and berries, the Paiutes had been swept up in the Snake War to defend their homeland 10 years earlier and suffered 20% fatalities before agreeing to settle peaceably at the Malheur Reservation east of Burns. They were by no means eager to go on the warpath again.

The Bannock War stemmed from white encroachment on the Big Camas Prairie in Idaho, a bulb-foraging ground for the Bannocks, another Paiute tribe. Most Bannocks opposed war, but after a shootout seriously wounded two white cattlemen (both survived), their chief, Buffalo Horn, convinced about 200 Bannock warriors they were in for war anyway and might as well make the most of it.

Meanwhile, the Malheur Reservation had its own problems: A benevolent Indian agent, Samuel Parrish, had been replaced by an autocratic one, William Rinehart, who brutalized the Paiutes at a time when Congress was cutting back funding for reservations due to the national depression of 1873-78, reducing food rations to four and a half cents a day per Indian.

When Chief Egan and the Paiutes abandoned the Malheur Reservation, in part to escape starvation, Rinehart diverted attention from his own abuse and mismanagement by spreading word that the Paiutes had left to join the Bannock uprising—with Egan at its head.

Wilson makes a convincing case that, in fact, hostile Bannocks coerced Egan and the Paiutes to take part, holding them hostage and threatening to take away their weapons if they didn’t join the fight. But once the region’s newspapers had a villain to blame for the Bannock War, they could attribute almost any perfidy or atrocity to Chief Egan.

In one Oregonian story, Egan is said to have grabbed a white peace negotiator by the hair, proclaiming, “Me have that in my belt heap soon.” (In fact, Egan and his followers sought peace and helped the white negotiators escape when talks with the Bannocks went awry.)

Eventually, Egan was killed during a retreat by Umatilla warriors allied with the U.S. Army. The defeated Paiutes would be forced to march from Fort Harney at Malheur to the Yakama Reservation in south central Washington, a frozen trail of tears stretching 350 miles through deepening snow.

Sarah Winnemucca, daughter of Paiute Chief Winnemucca of Nevada, embarked on a lecture tour to draw attention to her people’s suffering and persuaded Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz in Washington, D.C., to write a letter in January 1880 ordering the return of the Paiutes to the Malheur Reservation.

Due to the corrupt opposition of U.S. officials in the West, however, Schurz’s promises were never kept and the Paiutes remained at Yakama until 1882. When they finally returned to Malheur, the reservation had been dissolved. Many would live and scavenge food at the Burns city dump, sometimes wrapped for them by sympathetic local restaurants.

Wilson notes that whites, who viewed the practice of scalping with revulsion, thought nothing of decapitating the bodies of Chief Egan and other Natives and sending their skulls to Washington, D.C., for museum display and analysis to prove their racial inferiority to whites. (Chief Egan’s skull and that of his brother-in-law Charlie were eventually returned to Oregon in 1999 and interred under a stone memorial at the Burns Paiute graveyard.)

The greater irony, Wilson writes, is that white Americans tried to prove their superiority with the skull of a man whose good will was squandered by their own stupidity and shortsightedness: “Egan had supported U.S. interests since his surrender at the end of the Snake War. At every turn he had been guiding the Paiutes on a path of peace and cooperation…until whites’ incompetent and in some cases malicious mismanagement of the Paiutes led to his death.”

GO: David H. Wilson Jr. appears in conversation with Nancy Egan, great-great-great-granddaughter of Paiute Chief Egan, at Powell’s City of Books, 1005 W Burnside St., 503-228-4651, powells.com. 7 pm Friday, May 13. Free.