In 2013, when author and Portland State University professor Justin Hocking’s first memoir, The Great Floodgates of the Wonderworld, was about to be published, he began, as he describes it, to read “obsessively” about subterranean themes: geological texts, mining histories, Dante’s Inferno. “It has something to do with growing up in a place where so much was happening below the surface,” Hocking says. Glenwood Springs, Colo., Hocking’s hometown, is known for its many hot springs and vapor caves. “And in my home life, there was a kind of underground, too,” he says.

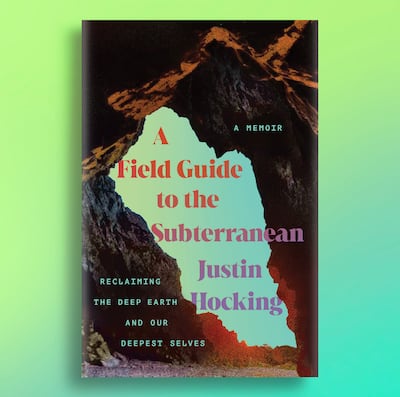

Hocking’s new memoir, A Field Guide to the Subterranean (Counterpoint press, 224 pages, $27), twines together the underground in many forms: literal and figurative, personal and historical, psychological and political.

Willamette Week caught up with Hocking recently to discuss the new book.

WW: Your book opens with definitions of the word “reclamation.” What kinds of reclamation caught your attention?

Justin Hocking: One primary meaning relates to the mining industry: reclaiming a site that has been mined and restoring the land to a more natural state. It’s often kind of a dubious project, but in some cases healing of the land can occur. I also latched on to the idea of reclamation as making a claim or protest, especially in the context of the underground on the political level. So many examples exist, like the French Underground in the Second World War and the Underground Railroad. The underground is laden with possibility and uncertainty, major potential and energy. It’s a powerful site of resistance.

The book is divided into three sections: Subterranean, Heights and Equatorial. Can you talk about what these designations mean?

The structure owes a bit to Dante’s Divine Comedy. The first section, “Subterranean,” excavates some difficult personal material from my childhood and shines a light on it. I found my way into writing about abuse through some interesting trap doors, for example by using Hogan’s Heroes—a ’60s-era TV show about a German [prisoner of war] camp with literal underground passageways and secret rooms. Reruns of this show were always on when abuse occurred in this particular house, so it kind of haunts me. The middle section, “Heights,” evokes the lost, searching quality of my early 20s—a kind of emotional purgatory. “Equatorial” chronicles my frequent travels in Costa Rica while aiming to problematize our Western notions of paradise.

Who are some of the writers who most influenced this project?

First and foremost in terms of direct inspiration would be Barry Lopez. He was such a generous, wonderful person, and one of my favorite writers. His whole life trajectory inspired the book: the way he transformed past pain and trauma into deeper empathy and care for vulnerable landscapes and peoples. On the other hand, the narrative pushes against Robert Bly and Iron John: A Book About Men—a text that unfortunately cast quite a spell on me during my 20s. Bly’s gender essentialist ideology helped spark the first wave men’s movement, which has slowly morphed into what we now call the manosphere. His idea of reclaiming one’s essential masculinity from a culture that’s trying to feminize and “soften” men remains insidious. My hope is that the story of my own lifelong negotiation of issues around gender and identity—and the embracing of softness as a radical act—might be helpful for younger men and folks of any gender expression.

Excerpted from A Field Guide to the Subterranean by Justin Hocking. Reprinted by permission of Counterpoint Press.

In the spring of 1992, at a New Age bookstore in Sedona, Arizona, my father bought me a copy of Iron John: A Book about Men by the poet Robert Bly. I was eighteen or nineteen and had no idea who Robert Bly was, or that Iron John would go on to spend sixty-two weeks on the New York Times bestseller list and launch an entire movement. I had some familiarity with feminism, but I’d definitely never heard of a “feminist backlash.” As a college freshman interested in the humanities, what I did have was a burgeoning love of mythology and the tracing of archetypal patterns across cultural narratives, so Iron John spoke to me. It’s embarrassing to admit now, but so did the book’s central precept that, while feminism was generally a positive thing, many men in the orbit of strong, feminist women had become too “soft” and “tamed” after consistently bartering away their masculine power for vulnerability and consensus-based decision-making.

After reading the first few chapters, I remember wondering, How do I measure up on the hardness scale? Am I too easily scratched? Reading Iron John tapped a desire to reach the upper levels on the scale—maybe even to become diamond-hard, scratchable only by another diamond.

But the damage and relentless sense of anxiety I carried from childhood dropped my score way down to the 2–3 level, at least in my mind.

Maybe, I thought, all the fear will go away if I can become enough of a man.

GO: Justin Hocking in conversation with Emily Kendal Frey at Powell’s City of Books, 1005 W Burnside St., 800-878-7323, powells.com. 7 pm Thursday, June 12. Free.