Eleven years ago, Marc Carpenter started researching Oregon’s Lane family. Its best-known member, Harry Lane, is remembered as one of the giants of the state’s Progressive era; he was a champion of direct democracy and the first to propose a “permanent rose carnival” that became the Portland Rose Festival. Lane was part of a political dynasty: His grandfather, Joseph Lane, was the first territorial governor of Oregon and the namesake of Lane County.

“They were kind of my first proper research project, and I thought 10 years ago that I’d have a nice, quick research project. It’d be over and done,” says Carpenter, who grew up in the Willamette Valley and now teaches history at the University of Jamestown in North Dakota.

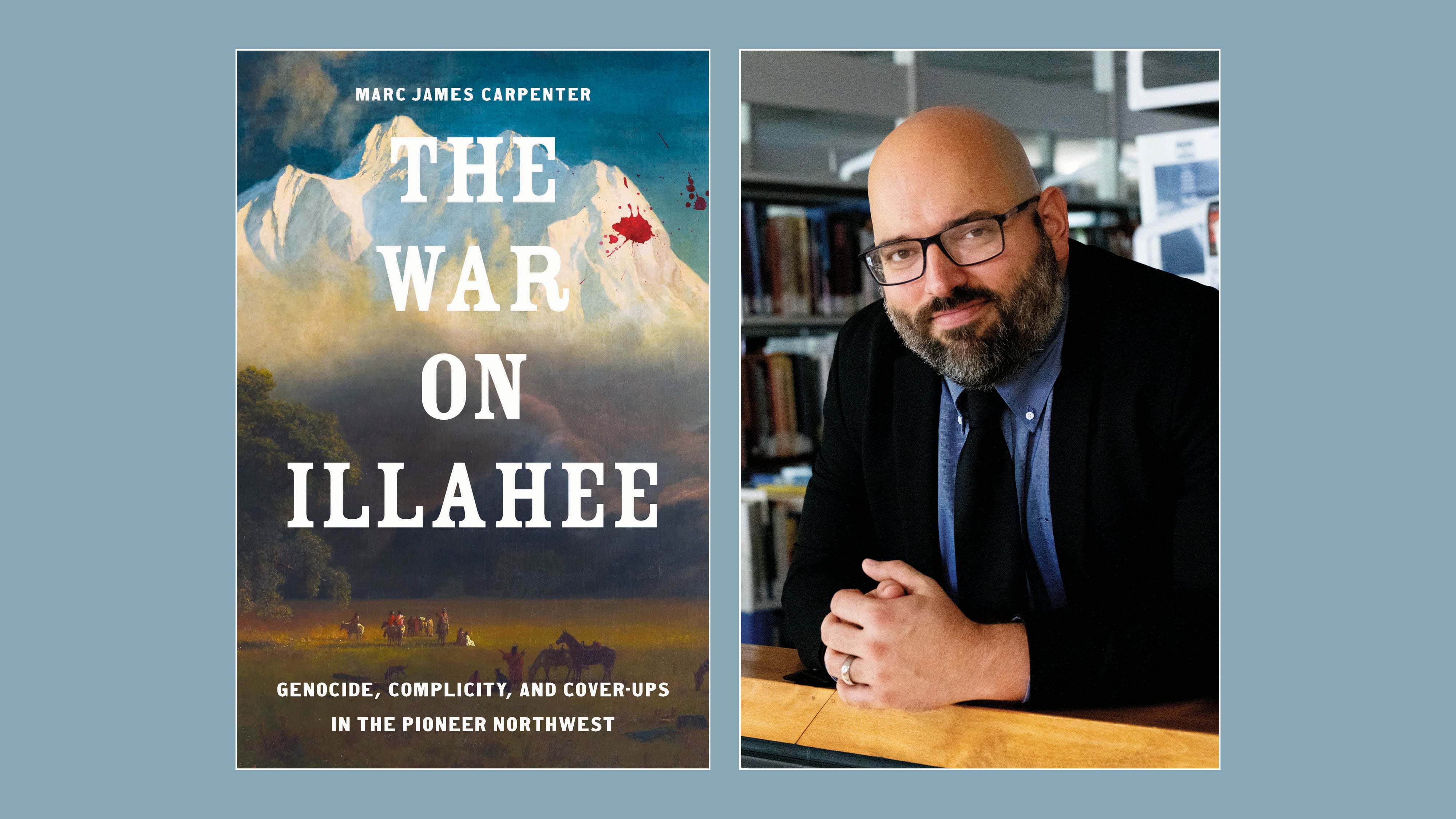

Instead, Carpenter fell into a rabbit hole that consumed the next decade of his life and resulted in the book The War on Illahee: Genocide, Complicity, and Cover-Ups in the Pioneer Northwest (Yale University Press, 400 pages, $38), published in October. It grew out of the discovery that Harry Lane was wrong about his own family, and that much of what he believed has persisted to modern-day teaching of history.

“He’s got many of the faults of [people of] the early 1900s, but he earnestly was an Indigenous rights activist. He’s very unusual for his era; he’d actually go and talk and listen to Native people, which is very rare even among Native rights activists in that period,” Carpenter tells WW. “And when he talked about himself, he talked about it as a family tradition. He would say, ‘We’ve always been doing this. My grandfather was like this.’ And a lot of the books that I read kind of made a similar point.’”

But primary sources tell a different story, Carpenter says. Joseph Lane wrote letters to newspapers admitting to killing Indigenous people, using openly racist language. Carpenter also says he found evidence that Joseph Lane sexually assaulted Native people, though he did not boast about the sex crimes in print.

“That was part of his political appeal, is that he was killing and—outside of print—raping Native people. That was part of how he got elected,” Carpenter says. “So I was flabbergasted. Like, how did not only Harry Lane get his granddad so wrong, but how is this missing from the story of Joseph Lane?”

And Carpenter found in the Lanes’ story a “sort of microcosm of a much broader story of Oregon,” in which the series of events known as the “Indian wars” are sort of tamped down and described as something that mostly happened elsewhere.

Carpenter is quick to acknowledge that the history documented in The War on Illahee—“Illahee” is a Chinook Wawa word that can mean “home” or “Native land”—comes from stories Indigenous people have been sharing with the broader world for generations. But as someone who’d always enjoyed history, Carpenter was startled that so much of the history was buried, yet not difficult to find once he started digging.

Not only were Oregon pioneers documenting atrocities against Indigenous people in public writings, he says, Progressive-era historians began corresponding with Native people to learn more about things like Native place names. And their correspondents would reply with detailed information about things that had happened to members of their family. Those historians never did anything with that information, though; the letters simply sat in archives for generations. And they began writing histories of the West that covered up the brutal details of its settlement.

It’s not a coincidence, Carpenter says, that historians began papering over the genocide of Native Americans at the same time that the Lost Cause myth—that the U.S. Civil War was a fight over states’ rights rather than slavery—began to emerge.

“I sometimes talk about it as the two original sins of America. It’s the colonialism and slavery,” Carpenter says. “And it’s striking that both of those stories are being sanitized in roughly the same time. In part it’s a response to something that is positive, where Americans are less comfortable with the horrific violence of the 1800s but are not yet willing to face it and so kind of cover over it.”

One thing Carpenter uncovered in his research again and again was the slogan “nits make lice”—a phrase found in print as early as the 1850s as a justification for murdering Indigenous children. That dehumanization was part of a long, ugly historical pattern of comparing marginalized people to parasites or vermin. But he also found another layer to it.

“One of the striking things I found was, people talk [in primary sources] about how they’d be sitting around a fire, kind of repeating that phrase just before they went and attacked a Native community. And I interpret that as, they’re kind of egging each other on to stifle their own humanity, right?” Carpenter says.

“Because it’s not a natural thing; we were not actually built to kill other people’s children. That’s not a thing human beings instinctively want to do, and so it does require maintenance to keep that kind of project of hate going. I think one of our roles as human beings, and hopefully historians, is to denaturalize it, to show that this is something that requires work and something that can and should be rejected.”