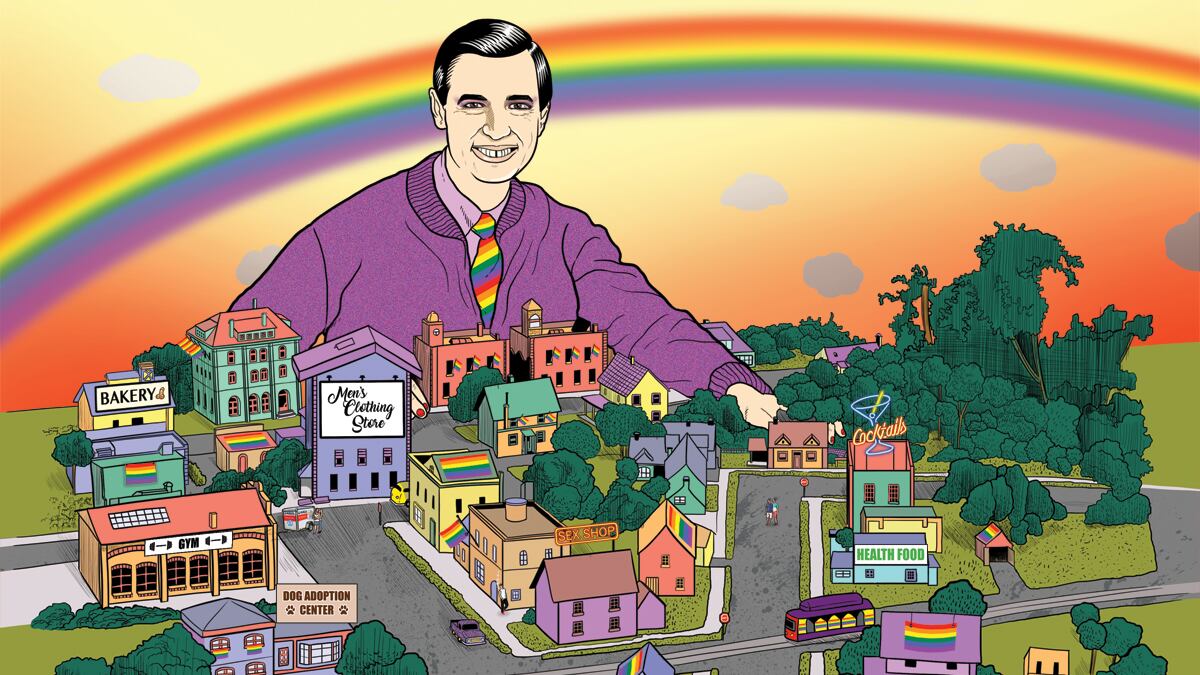

San Francisco's got the Castro. Chicago has Boystown, and New York has Greenwich Village. Even Seattle has Capitol Hill—but where's Portland's gayborhood?

Among major U.S. cities, only San Francisco has a higher percentage of LGBTQ residents. But ever since the collapse of Southwest Stark Street's Pink Triangle, Portland's LGBTQ population has no cultural home.

And we'll probably never have another one: Nationally, gayborhoods are a dying breed.

Partly, it's because of old-fashioned gentrification—think Ace Hotel and the West End restaurant scene. But other reasons behind the decline of so-called lavender ghettos are less obvious.

According to a recent article in The American Prospect, among the biggest culprits are dating apps that make gay clubs less necessary to find partners. And paradoxically, another reason is LGBTQ political advancements. Without much of a legislative agenda, big cities are finding gay unity to be less of a necessity—and more straight people are moving into historically gay enclaves than their queer peers.

If you ask most people why Portland doesn't have a proper gayborhood, they'll proudly retort, "Everybody's kind of gay in Portland" or "We're all liberal, though."

"Portland is such a blue bubble, we don't have the need for those types of enclaves like other parts of the country still do," says Susie Shepherd, an early LGBTQ advocate who masterminded the 1976 booklet "A Legislative Guide to Gay Rights" for the Portland Town Council, an early local gay rights group.

But it's easy to forget that progress isn't guaranteed. Just days after the U.S. elected an administration whose vice president wanted to jail same-sex couples applying for marriage licenses, the bathrooms of liberal bastion Reed College were plastered with slurs, with a chilling moral scrawled in Sharpie: "The white man is back in power, you fucking faggots."

But it's unclear whether the sorry state of national politics will lead to more interest in a sustainable LGBTQ district in Portland.

"With the coming administration, it depends on how much hate crimes start increasing again since before reform," Shepherd says.

It might be impossible for Portland to establish a traditional gayborhood. But there's reason to believe that's a good thing. Here's why.

We're too liberal.

Gayborhoods have traditionally been hubs for those yearning to unite in order to fight for civil rights, open LGBTQ-related businesses, combat discrimination, or simply feel at home. And though Portland does still have gay bars and clubs, these bars are peeking out from an open casket, and their numbers continue to shrink. Last year, Portland lost another—the all-ages venue the Escape.

Portland was one of the first cities with an openly gay mayor, Oregon still has the nation's first openly LGBTQ governor, and city commissioners recently decided to make two-thirds of city restrooms gender-neutral.

Basic Rights Oregon, the state's largest LGBTQ rights-oriented organization, says it's focusing its efforts outside of Portland city limits—hinting that the city is running out of battles to win.

"Two decades ago, much of Oregon was hostile to the LGBTQ community," says Amy Herzfeld-Copple, co-executive director of BRO. "In fact, this state was ground zero for anti-LGBTQ hate. Our work is more important than ever with this election, particularly in small towns and rural communities."

Let's not forget that Gresham was home to the notorious now-closed Sweet Cakes by Melissa, a bakery that refused to make a wedding cake for a lesbian couple in 2013.

Even as gay spots have been vanishing from Portland, they've been sprouting in smaller cities. Until 2014, Eugene didn't even have a monthly gay event. And it wasn't until the Wayward Lamb opened in 2015 that Eugene finally got a queer taproom designated to ignite community outreach. Likewise, Salem now has a gay bar, Southside Speakeasy, but that wasn't the case a couple years ago.

Gayborhoods are outdated.

Recently, the LGBTQ world has finally offered more visibility for the B, T and Q parts of the acronym—people who identify bi, trans or queer. Today, a burgeoning gayborhood couldn't be labeled a gayborhood. It'd have more success as "the LGBTQuarter."

For a social minority long symbolized by a rainbow, gender is only now becoming less black and white.

"I remember in the '70s, the area around Northwest 21st [Avenue] was referred to as Vaseline Hill because, you know," Shepherd says. "That was the area for gay men. Lesbians lived in the 97214 zip code [of inner Southeast Portland]. Most of the bars were downtown and catered toward gay men, and now if any of those places are left, they cater toward gays and straights."

In Portland, the divide between gay men and women may have been mostly logistical.

"Many gay men lived in Northwest, which was close to downtown and had a huge supply of older and lower-cost apartments," says George T. Nicola, an early member of the Portland Gay Liberation Front and the author of a 1973 Oregon House bill that laid the groundwork for banning discrimination based on sexual orientation. "Some young gay men were at the time more likely to rent apartments rather than buy homes, partly because they usually did not have kids. And because of job discrimination, some gay men worked for the service industry, mostly as waiters. Many of the restaurants where they worked were downtown."

Shepherd says she spent most of her time with gay men, despite being openly lesbian.

"Many of the women at the time, 1976-77, were so separatist," Shepherd says. "They wanted to own houses and were thinking about extended family. I hung with the guys because I didn't want to go to tofu potlucks and process my feelings."

There's no room.

There's a reason the Pink Triangle, Vaseline Hill and the Buckman neighborhood hub of '70s lesbian life died out before relocating.

Portland has a housing crisis, which means all neighborhoods are in demand by everybody—genderqueer or cis-straight-white. There's pretty much nowhere west of I-205 where any group could plausibly carve out a space for itself, even if those identifying with the group could afford it.

"Everybody was moving here and rents tightened," Shepherd says of the death of Vaseline Hill. The Nob Hill neighborhood is now the city's sixth most expensive neighborhood.

These housing-cost increases may not be a coincidence. It's already a fact of real estate that gay neighbors raise property values—a perception supported by a Harvard Business Review study in 2012.

But in more conservative areas like Gresham, the introduction of gayborhoods is linked to lower housing prices because homophobic neighbors reject living too close to LGBTQ residents.

If housing prices continue to skyrocket in Portland and the local LGBTQ population feels politically vulnerable, the community could logistically set up shop in the suburbs.

That sounds awful, though. Gayborhoods aren't store-bought; they're made from scratch. And in Portland, the ingredients are unavailable.