In the 101 years of Camp Namanu history, it’s safe to say that 2024 was the most tumultuous.

The highs were high. In March, the sleepaway camp in Sandy earned a spot on the National Register of Historic Places. The National Park Service honored the 552-acre camp, one of the largest and oldest youth camps in the region, for its “important social and architectural history.” For Namanu’s (pronounced nuh-mah-NOO) centennial birthday last spring, the Oregon Historical Society hosted an exhibition about the camp in its downtown museum.

The lows were, arguably, even lower. On Nov. 1, Camp Namanu leadership had to write a message to supporters that the organization behind Camp Namanu, Camp Fire Columbia, was just eight weeks from going under. That kicked off an ambitious fundraising campaign to come up with $1 million and a complete restructuring of Camp Fire Columbia.

And yet, starting June 22, the camp will welcome its first crop of campers for the season for a week of singing, s’mores, hiking, and telling the legend of the elf who lives in the tallest tree at camp, Mr. Skriggleboggle. Gina Sander (camp name: “Sprout”), executive director of Camp Fire Columbia, is still recovering from the whiplash of 2024.

“There is a path forward outside of this, which is wild, because six months ago it was so unclear,” Sander says. “It was touch and go for everyone’s jobs. We didn’t know if we would be around at all.”

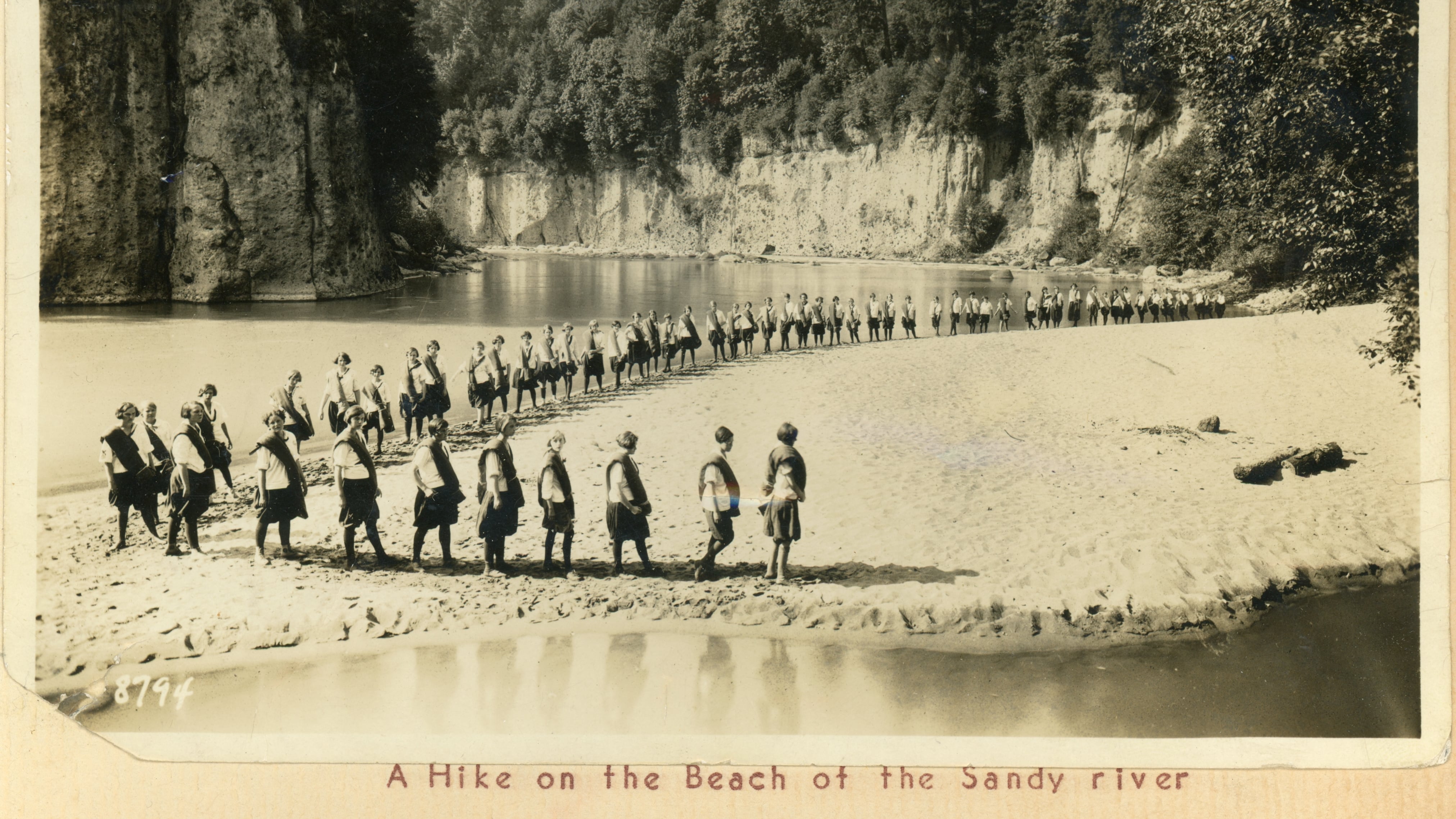

Camp Namanu was founded in 1924 as an all-girls camp, part of an organization then called Camp Fire Girls, which served as a sort of counterpoint to the Boy Scouts of America. Namanu sought to give the type of leadership and outdoor recreation opportunities to girls that already existed for boys. Namanu welcomed boys for the first time in 1979 (current breakdown: 50% girls, 25% boys, 25% nonbinary). The camp has also served as an Outdoor School site since 1999.

Prior to last year’s tumult, Camp Fire Columbia hosted two other major programs in addition to Camp Namanu: a teen program and a before- and after-school program. Both of those were shuttered to save money, though the YMCA Columbia-Willamette absorbed the latter, including some of the staff. All told, Camp Fire Columbia lost about 90 employees last year, many from the school-based programs, and is down to just eight year-round staff. (Camp Namanu employs about 60 seasonal staffers, such as counselors and cooks, too.)

The fundraising campaign brought in $425,000 in November and December, Sander says. The effort continues with a July 19 gala in the meadow called Shine and a “Pave the Way” fundraiser to sell engraved bricks near the main fire ring at camp.

What brought Camp Fire Columbia to its dire situation in November was, chiefly, declining individual contributions and government support, Sander says. Compounding those challenges were increased costs, especially for food, and decreased registration for the school-based programs. While Camp Fire Columbia reached only about half of its original $1 million fundraising goal, that income, plus the much leaner payroll and slate of programming, has stabilized the organization. “There’s a light at the end of the tunnel,” Sander says.

Namanu features lodges designed by Pietro Belluschi, an Italian American architect who worked in the back-to-nature movement of the early 20th century, which romanticized the American landscape. The National Park Service praised Namanu’s “rustic wooden buildings blending seamlessly with the surrounding meadows, forests and river.”

The Oregon Historical Society hosted the centennial exhibition last spring based on the historical heft of Camp Fire Columbia and Namanu. Artifacts included Camp Fire patches and songbooks.

“Our mission is to tell a broader history of Oregon—it’s not just what you think of as the important names and faces and what you see in textbooks, but outdoor recreation and organizations that have shaped people’s lives at any age,” says Megan Lallier-Barron, OHS curator.

Namanu remains a place where children can connect with themselves, each other, and nature. No phones are allowed. Some of Namanu’s cabins are tree houses with no walls; campers fall asleep to the sound of the Sandy River rushing by and wake up to birdsong. (Those are for the bigger kids, though—the second and third grade Blue Wingers have electricity and indoor plumbing.)

This is the first summer with this new, slimmed-down administrative staffing model. Namanu is expecting about 1,400 campers, but there are still 55 spots left for any families who still want in. Sander is feeling “confident, but it’s nerve-racking, being in this year of firsts.” Campers shouldn’t notice a change, but parents might need to be patient with email and phone message response times, she says.

One thing that has not changed in 101 years: the voluminous amount of singing.

“So much singing,” Sander says. “I had a camper a couple of years ago say, ‘I feel like I just stepped into a musical.’”