If you've spent any time walking the trails of Mount Tabor Park, you've probably seen the historic lampposts scattered throughout the forest, seemingly at random. California transplants are apt to notice them, and they will ask me quite earnestly, "Do they serve a practical purpose? Anything at all?" Then they might take it a bit further, "Do they even turn on?" I look deeply into their azure Californian eyes and say, "No, they're purely aesthetic. They don't even turn on! They're just here to charm you."

Real Portlanders know the truth about the lampposts, which were installed in Mount Tabor Park to mitigate the very serious crime plaguing the park for much of the city's history. We take our modern, cleaned-up, Disneyland version of Mount Tabor for granted, but it hasn't always been like that.

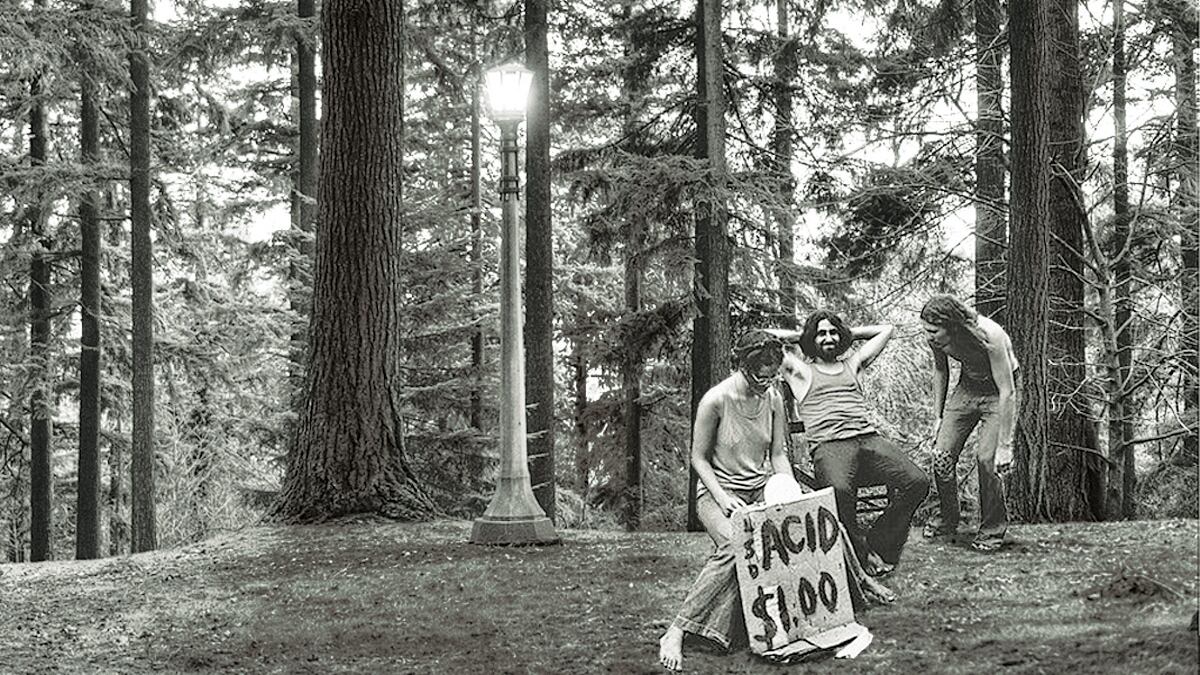

In the city's earliest days, counterfeit-goods hawkers and three-card Monte dealers moved into the park. During Prohibition, bootleggers started using the park as a favorite hiding place for barrels of illegal alcohol. Muggings and knife attacks in the park surged in postwar Portland. In the 1960s, it became a favorite place for flower children to score LSD and grass.

Before the freeways, the engineering feat of Southeast Thorburn Street and the widening of Powell Boulevard, the roads through Mount Tabor Park used to be among the city's most vital thoroughfares. If you lived in "East County," especially, the park was an unavoidable part of your daily commute. The grifters, rowdies, vandals and street toughs were attracted to this high volume of foot traffic for its never-ending stream of potential victims. It got so congested during rush hour that they would set up frankfurter stands to lure you out. And once you were out, you were a mark, quickly embroiled in a dice game—or worse.

It isn't clear exactly when—probably sometime in the 1950s—Portland cops responding to calls at Mount Tabor Park began using a shorthand when filing reports involving these so-called "Mount Tabor Villains." That was shortened to "Montavillains," a name that stuck and became the basis for the name of the adjacent neighborhood, which had previously been known as "the Backside."

When I was 16, I got a job driving a cab at night. Anytime you got a call east of 50th Avenue, you knew you'd inevitably end up having to pass through Mount Tabor. You would look out the window and see the depravity going on all around. I won't lie, it weighed on you. But at the same time, it was hard to look away. Sometimes I'd drive through Mount Tabor even when I didn't have a passenger. It might be raining, but I knew it wasn't enough. If ever there was to be a change, we needed a real rain to come and wash all the scum off the streets.

In 1979, Frank Ivancie campaigned for Portland mayor on a platform of fixing Mount Tabor Park, making it appeal to families and "good, nice, normal" Portlanders by installing lamps, increasing police patrols, building new roads around the park and closing the roads in the park. This was known as the Ivancie Plan, and years later New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani used it as a model for his initiative to clean up his city's version of Mount Tabor Park—Times Square.