Steve Hackman was in his first assistant conducting gig when he began to feel disconnected from both the pop music he cherished and other 20-somethings. So he quit.

A recent graduate of Philadelphia's prestigious Curtis Institute, Hackman began writing arrangements of pop hits for fellow Curtis alums Time for Three, a classical trio that draws broad popular audiences via informal performances and rock band and stage appeal. That led to a series of jobs—in Indianapolis, Pittsburgh and Colorado—running the alt-classical programs more and more orchestras are creating to attract younger, more diverse listeners.

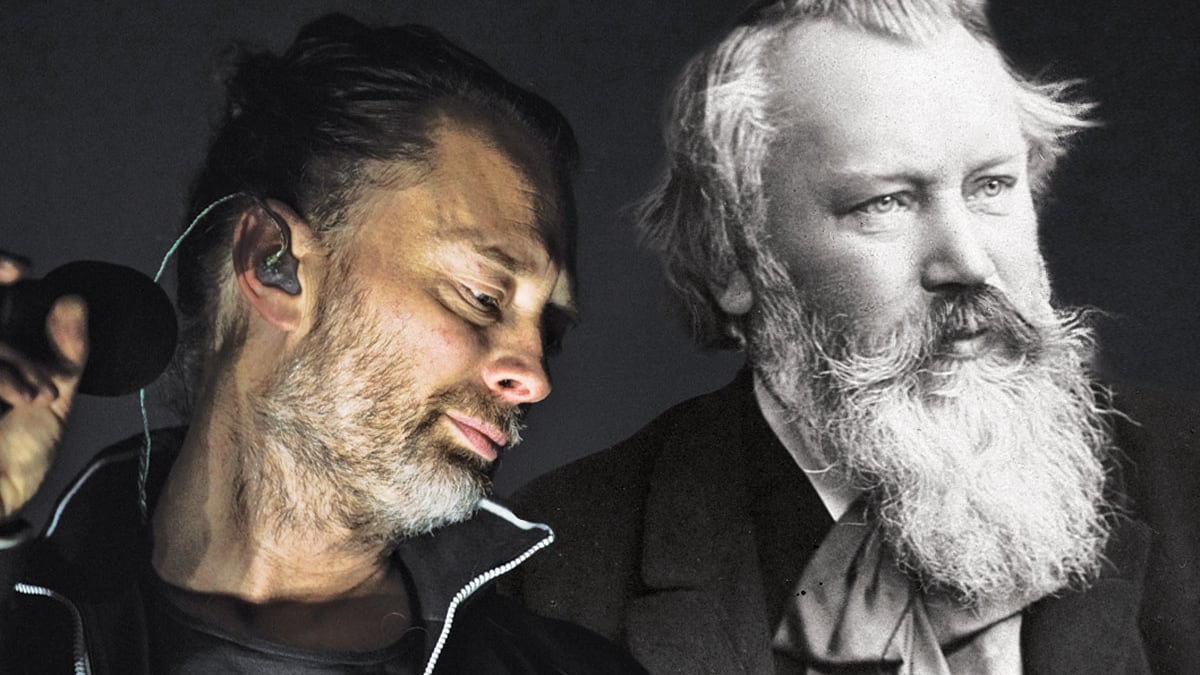

A few years ago, Chapman created something more than simple juxtapositions. He fused a quintessential Romantic symphonic classic, Brahms' 1876 Symphony #1, with songs from Radiohead's landmark 1997 album OK Computer. He'll conduct it with the Oregon Symphony and three singers this week.

"Fans of Radiohead are going to hear this music they love through a different lens," Hackman says. "And they're gonna see it played by one of the best bands they've ever seen."

Along with rich harmonic complexity and counterpoint, he found a dense, dark brooding gravity infusing the music of Radiohead—a favorite of classical musicians made up of classically trained musicians who've made their own orchestral projects—and angsty Brahms. Sometimes the songs float above Brahms' music, others are interpolated between movements. Musical themes slide from one to the other, or the songs are altered to fit the symphonic sound world.

Brahms vs. Radiohead set the template for Hackman's subsequent pop-classical mashups: Bon Iver with Copland, Coldplay with Beethoven, Bjork with Bartok, even his own original music with Stravinsky. (He's also promised to do Kid A eventually.)

While Hackman's mashups have drawn strong, younger audiences to symphony halls, some critics prefer their genres separate but equally valid. Some classical purists regard such experiments as a cynical ploy to "youthify" and broaden audiences, and lend a facade of hipness and relevance to a backward-gazing genre. Pop fans worry, with equal justification, about bloated arrangements diluting the lean power of pop in a search for high-culture legitimacy.

But Hackman, who grew up on pop music, competed on American Idol and has also recorded albums as a singer-songwriter, praises orchestras like the Oregon Symphony for their recent embrace of many such pop-classical hybrids. He sees his "syntheses," as he prefers to call them, as a gateway to bring pop fans to the classical arena he equally cherishes—and vice versa.

"This is not a symphonic treatment of Radiohead's music as much as it is a true synthesis of it with a symphony of Brahms," Hackman says. "By the end, you will have heard the entirety of Brahms' first symphony, and I guarantee you're gonna be curious to hear more. I've had so many listeners come up to me after one of these shows and say, 'I'm gonna go home and listen to this again.'"

SEE IT: Brahms v. Radiohead is at Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall, 1037 SW Broadway, on Thursday, Jan. 4. 7:30 pm. $25 and up. All ages. Get tickets here.