Harahan Fats (Goner Records) sounds like a ‘50s swamp-pop record for about five seconds until the voice of King Louie Bankston enters to let you know it’s not; the late garage-rocker, who died last year at age 49, sounds like the goofy and immensely likable Gen X kid he still essentially was (the cause of death was never revealed by his family).

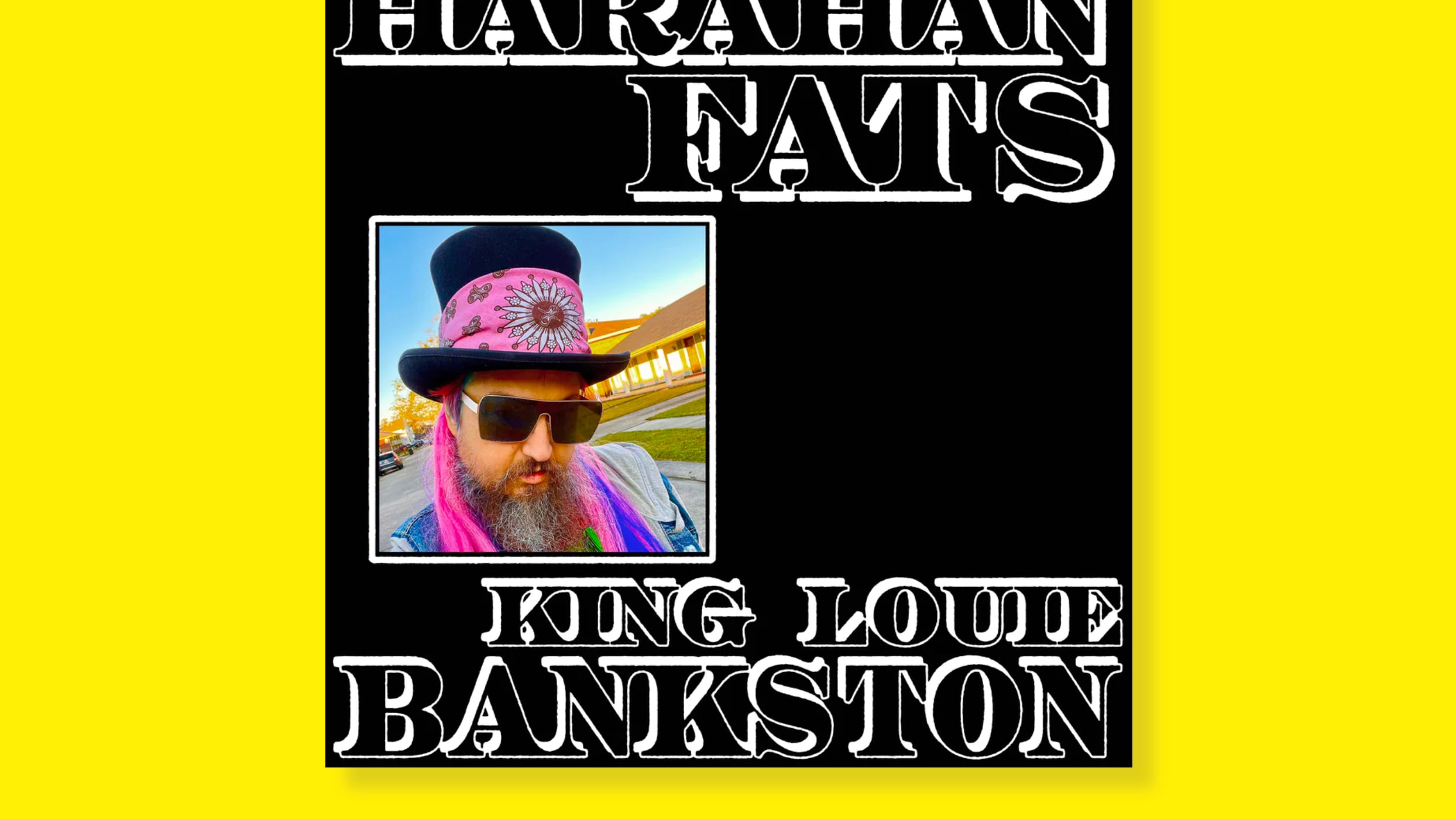

The cover of his posthumously released album shows the Harahan, La., native dressed as some sort of cut-rate Dr. John, a parody of the grand personalities that spring up in the Southern swamps. And while Louie had the Louisiana bona fides to play such a character convincingly—note how he refers to America’s most beloved rodent as a “nutria rat,” as is done only in his home state—he must have agreed with the Northwest’s own Calvin Johnson that “rock ‘n’ roll is a sport for teenagers of all ages.”

Louie lived in Portland for only a few years, when he was intimately involved in the production of the legendary local power pop band the Exploding Hearts’ sole record, Guitar Romantic. Louie co-wrote nearly every song on the album (notably “I’m a Pretender,” one of the best modern-day pastiches of ‘70s pub rock ever recorded), and at the end of the band’s existence, he was in talks to become that rarest and most archaic of things: a nonperforming songwriter, like the Grateful Dead’s Robert Hunter and houseboat-era Pink Floyd’s Polly Samson.

Louie might’ve gotten a kick out of this arrangement, but his writing partner Adam Cox and two other members of the Exploding Hearts fatally crashed their tour van near Eugene in 2003, ending the band and any chance of future collaboration.

Local singer-songwriter (and sometime WW contributor) Mo Troper defines power pop as “wimps with deafening guitars.” This music doesn’t sound like power pop, but it feels like it at times. The guitars on Harahan Fats are often acoustic and generally more grating than deafening, strummed with primitive skill, but Louie certainly had a crucial quality in his voice, not so much that of a “wimp” as a sincere desire to be loved and to be hugged. His harmonies are simple and consonant, descended from the Beatles and their imitators.

The songs aren’t all about girls, but when they are, they’re endearingly sweet; “Places Like This” is about how he thinks of his girl every time he walks by a crab shack. (A listen through Harahan Fats will inspire you to find the nearest Cajun restaurant.)

Louie struggled with substance abuse for much of his life, and his uncompromising exploration of that theme cuts sharply through the goofy hoodoo cosplay. “Rehab Legend” is a cover of an unsparing and painful song by obscure Los Angeles MC Cadalack Ron, known mostly for shooting up in the middle of a rap battle. “Trinkets” is a cover of late garage-rock dynamo Jay Reatard, a pillar of American garage rock before his fatal OD in 2010, with whom Louie performed in the supergroup Bad Times.

Louie writes about drugs in a did-he-really-say-that kind of way devoid of self-pity; he craves not the distant empathy of non-addicts but the sympathy of anyone who truly understands what he’s talking about. It’s a tone you often see in folk punk, or in Neil Young’s most dissolute work from the mid-’70s. It is generally not accompanied by virtuosic playing or singing.

Harahan Fats is crude, first-idea-best-idea music, apparently cut by Louie in one or two takes, much of it seemingly improvised off the cuff. (On “Trinkets,” the bass note causes the snare to buzz.) Several tracks are a capella, including the aforementioned “Places Like This” and “Down and Out,” the latter with goblin harmonies that bring to mind the music of fellow Louisiana legends the Residents. “Gentilly Woman” tortures a banjo in a way more suggestive of confrontational ‘60s German proto-punks the Monks than anything from the American roots tradition.

This is all par for the course in garage rock, especially when it’s released by Goner Records, whose flagship acts like Reatard and the Oblivians dialed down the sophistication knob until “Surfin’ Bird” sounded like Beethoven in comparison. And yet there’s the sneaking sense that Louie hoped this would be a masterpiece—maybe not his final one, but at least an opportunity to spread all sides of his personality across one physical package.

Across the album’s 15 tracks, we see the tortured soul and the beloved community pillar, the power-pop schlimazel and the gutbucket swamp-blues rapscallion—the grandiose persona and the wild-eyed kid behind it all.