Conventional wisdom maintains that when punk started, the likes of the Sex Pistols and the Ramones leveled the playing field and put music back in the hands of the people—people who often picked up instruments and started bands before even learning how to play them. But, Sid Vicious aside, most of the first generation of punk musicians knew how to play, and play well. And one of the finest drummers to allow punk to derail his life and career was a Portland boy named Sam Henry.

"I was born legally blind," says Henry while leaning his face into a menu at Side Door. "So I had extensive ear training when I was very young, and I didn't know it. I just started building drum sets out of like tinker toy cans. I used chopsticks. I just wanted to play drums. That's all I wanted to do."

And that's pretty much exactly what he's done. Over almost 50 years as a working musician, Henry has applied his intricate percussion power to some of Portland's most crucial bands, including the Wipers, Napalm Beach and the Rats, Fred and Toody Cole's pre-Dead Moon band. Of late, he's touring and recording with the garage-punk quartet Don't.

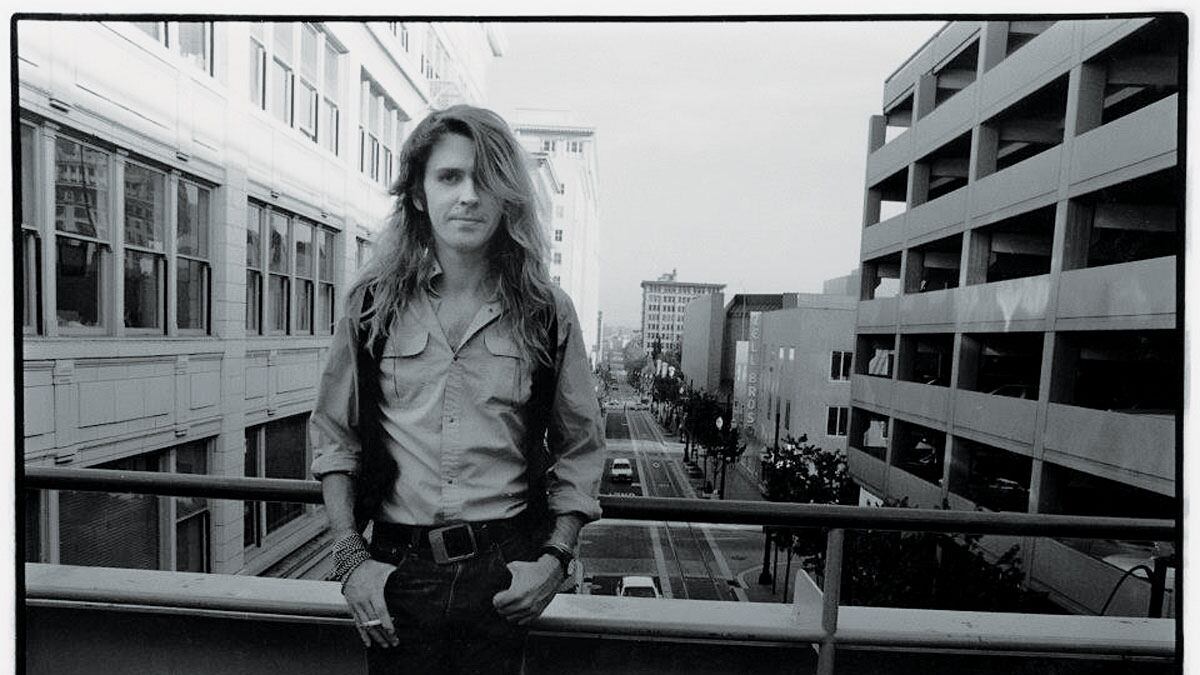

As he prepares to turn 60, Henry has become something of a patron saint of Portland punk. While many of his peers have slowed down, left town or passed on, he's still here, often posted up at Old Portland haunts like My Father's Place, telling stories behind a line of empty glasses. He is the definition of a lifer—a musician with the chops to write his own ticket, but who prefers dive bar gigs.

"I think the whole punk rock thing kind of turned me into a bad rebel of some sort," he says. "But in other ways it made me stand out as somebody."

Henry was born in Oregon City in 1956 and grew up in the Milwaukie area. He was weaned on his older sisters' Mickey Mouse Club 45s and found encouragement since his mother played the organ. When he was only 10, his father dragged him to the bar at the Hoyt Hotel, where he worked, to see jazz drummer Buddy Rich. "My mouth dropped open," he says. "I had never heard drumming like that in my life." Within a year, Henry had a kit of his own. By 12, he was playing in clubs six nights a week. "My mom would drive me with my little drum set and I'd play in little country-western bands in Hillsboro, weird places," he says.

Around age 19, Henry met Portland punk pioneer Greg Sage, who drafted Henry into his band, Hard Road. The two bonded over being outcasts. "He got picked on for being different because of his hair in school," Henry says. "And I got picked on my whole life for not being able to see." Eventually, Hard Road would become the Wipers, the Northwest punk band that would eventually influence everyone from Nirvana to the Melvins. After the recording of 1980's Is This Real, The Wipers relocated to New York. The band was not well received there, so Henry decided to quit and come back home to Portland while the Wipers continued without him.

Back on the cattle company circuit, Henry was offered a position in the Rats, the band that would later become Dead Moon, and also began working at Fred Cole's guitar shop, Captain Whizeagle's. Simultaneously, he joined nascent psychedelic punk band Napalm Beach. When Cole learned of Henry's double dipping, he offered Henry an ultimatum: It's either the Rats or Napalm Beach. He chose the latter, and Cole fired him—from both jobs.

The years with Napalm Beach finally got Henry over to Europe. In fact, he was the first member of the band to get his passport. Substance abuse was rampant within the band, however, and it never reached its potential. Henry had some hard years himself, though he worked through it much quicker than his bandmate, guitarist Chris Newman. Getting clean, "took a while," Henry says. "I had to go to jail. So did he. We all went to jail. A lot of people did."

By age 49, Henry was offering drum lessons by day, and still gigging at night. He tried going back to school, but when academic advisors forced him to take drum lessons he didn't need, Henry lost patience. "I'm like, look, I'm legally blind. I've been playing music all my life," he says. "I'm not going to make any more money playing at Dante's or Club 21 having a degree in music."

The reason Henry had wanted to play in Napalm Beach in the first place was to jam with bassist Dave Minick, who quit the band the day before Henry joined. A few years ago, Henry began writing songs with singer Jenny Connors, and Minick was invited into the fold to form Don't, beginning a late-career chapter in Henry's rock'n'roll life.

If there were any way to crown Henry with lifetime achievement beyond his 2011 Oregon Music Hall of Fame induction, it would be to come full circle and share the stage with the band that started everything for him. A Wipers reunion would help Henry get the widespread recognition he deserves. But so far, Sage is holding out.

"It's so crazy. Everybody wants the Wipers to do a reunion," Henry says. "But then it's like, 'Well, [Greg] won't do it with Sam and [bassist Dave Koupal].' Well that's what people want. That's the real band. If we could just play for a week, we could retire."

Henry isn't bitter, though. He admits his career has been defined by being "in the wrong place at the wrong time." But he remains humble, almost to a fault.

"I'm proud of just being able to continue doing this," he says. "I'm just proud of being able to be 60 years old and keep playing and touring and proud of doing something that I actually believed in. Didn't know half the time what I was doing, but just stuck with it."

SEE IT: Sam Henry's 60th Birthday Blowout is at the Liquor Store, 3341 SE Belmont St., with Poison Idea, Napalm Beach and Don't, on Wednesday, Dec. 28. 9 pm. $15. 21+.