Over the weekend, Congress passed a bill to direct the federal government to return the nearly 9,000-year-old remains of Kennewick Man to Pacific Northwest tribes.

The passage comes as part of the Water Resources Development Act of 2016, which states that the Corps of Engineers "must transfer the human remains known as Kennewick Man or the Ancient One to the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation on the condition that it dispose of and repatriate the remains to the Indian tribes."

"It's an undiscoverable feeling. It's a big victory, a very big victory and this is going to send a message out to Indians and non-Indians," says Armand Minthorn, a member of the Board of Trustees for the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Reservation. "Our elders and the tribes that encouraged us and supported us told us over and over, 'never give up on your ancestor. Keep fighting. And that's what we did. It is true that good things come to those to wait."

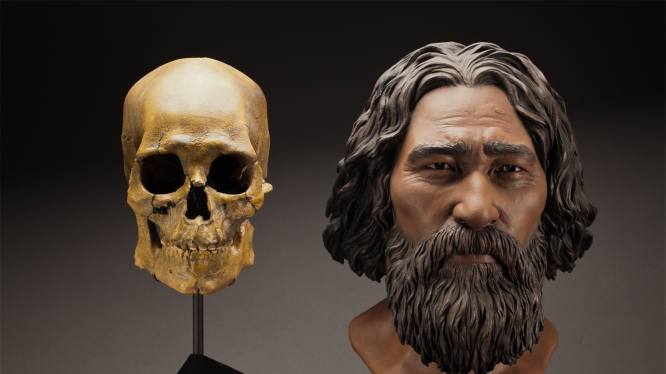

In 1996, two college students stumbled upon the skeletal remains of a prehistoric man on the bank of the Columbia in Kennewick, Washington, northeast of Portland. He came to be widely known the Kennewick Man, or the Ancient One.

Five Pacific Northwest tribes: the Umatilla, Nez Perce, Yakama, Wanapum and Colville tribes wanted the remains returned to them for reburial, as part of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, which was enacted to return cultural items kept by museums and federal agencies. But scientists argued that they were exempt from the law because Kennewick Man resembled a Polynesian or Southeast Asian person.

What followed was a nine-year legal battle between the United States Army Corps of Engineers, who oversee the land where the remains were found, scientists, and the tribes wanting to give him a proper burial.

In 2004, a federal appeals court upheld a Portland judge's ruling that said modern tribes can't claim the remains, as they were too old to be able to determine if he was a part of the Pacific Northwest Native American tribes, allowing scientists to study the remains. They published the findings 10 years later.

But in 2015, scientists at the University of Copenhagen studied Kennewick Man's DNA, finding that he was in fact most closely connected to the Native people of the Columbia Plateau, prompting public officials to call for the Army Corps of Engineers to return the remains to the tribes.

Now, that repatriation will finally happen, as soon as President Obama signs the legislation.

"I can't help but think though the 20 years, all the people that were involved all the controversy and how we, as the five tribes, dug our heels in and maintained for 20 years that this individual is Native American and this ancestor needs a proper respect shown and we want to rebury him," Minthorne says.

The Ancient One will then be returned to the five claimant tribes, including the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, which is comprised of the Cayuse, Umatilla, and Walla Walla tribes.

The five tribes will then work together to place him at rest at an undisclosed location.

"These past 20 years, the bottom line that is really clear is: It's just better if we get along with each other and make time to get to know how another people live and what they live by and not be so quick to judge," Minthorn says. "If people could make that time to understand a little bit about who we are and why we live the way we do and why ancient remains are sacred to us—a lot of people don't understand that—but if they could make that time, it might get easier."