It was an unseasonable 91 degrees in Portland last June on the day Multnomah County officials locked Greg Anderson out.

Anderson was the chairman of a unique citizen committee created to connect county residents with county officials. But he and his two other committee leaders had been the subject of more than 30 complaints—charging they had engaged in "unprofessional" and "disrespectful" behavior, bullying female colleagues and county staff.

That's how members of the Multnomah County Citizen Involvement Committee found themselves denied access to their meeting room at the county headquarters building at 501 SE Hawthorne Blvd.

Anderson says a staffer for then-Commissioner Loretta Smith came to the rescue, opening a sixth-floor conference room for them.

"It was ridiculous," Anderson says. "We were lucky because Commissioner Smith was the only one on our side."

That bizarre episode led to a meltdown now unpacked in an investigative report released to WW on Jan. 19 in response to a public records request. The report sheds new light on why the Multnomah County Board of Commissioners voted to "fire" the members of the CIC, although they are volunteers.

Even in the hyper-engaged, process-loving world of Portland politics, you'd have to go a long way to find a stranger situation than the implosion of the committee known as the CIC. It's a story that features a convicted crack dealer, big political contributions and the use of labor-union resources for brotherly love.

But on a more fundamental level, the abrupt dismissal of all 15 members of the citizen committee highlights the increasingly fraught relationship between government and the governed in this city.

Public comment periods at the county, Portland City Hall and other local governments are marked by disrespect, open hostility and defiance. This month, City Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty raised hackles by rebuffing the public for rudeness and "white male privilege."

Multnomah County's frictions are lower profile, but no less toxic. And county officials, on the receiving end of such aggression every week, responded to their rebellious volunteers with a time-tested method: They voted the incumbents out.

The Portland Tribune previously reported on the committee's dysfunction and the county's vote to disband it—but the new investigative report and other public records show why a powerful union and one disgruntled county commissioner broke ranks with the board.

Anderson, the only one of the three CIC chairs who agreed to be interviewed by the independent investigator, said the result of the investigation was exactly wrong.

"The accusations are trumped up," Anderson tells WW. "The staff bullied me and Chair [Deborah] Kafoury's office bullied me."

Kafoury says that's not true—and echoes Hardesty's warning that a few loud men were drowning out other public input.

"The current board highly values community participation, and that just wasn't happening," Kafoury says. "Voices were being silenced and we had to act."

Over the past 40 years, Greg Anderson held a variety of jobs in banking and mortgage finance in Lane County and on the coast. A longtime civic volunteer, he served as mayor of Florence in the 1980s. But after a divorce, he turned to drugs, eventually dealing to fund his addiction.

"I was leading a double life," he says.

In 2008, he was arrested in Springfield for dealing crack. He served 28 months in federal prison.

When Anderson left prison in 2011, he wanted to avoid his old friends. He moved to Portland and later volunteered to join the CIC.

Anderson was joining a committee with a long history and unusual power: Voters established it in 1984 and decreed it would serve as a conduit between citizens and the county board and have its own staff.

"I'd been involved in public life for decades and had never heard of a citizen committee with its own paid staff," Anderson says. (Kathleen Todd, the former longtime staff director for the CIC, says she also thinks the arrangement is unique.)

The CIC originally formed during a period of discontent: Many residents were apoplectic about the city of Portland's annexation of East Portland, for instance.

But according to the investigative report, the committee, under Anderson's leadership, devolved into bickering and dysfunction tinged with sexism.

"Anderson made others feel uncomfortable by hugging them and using terms 'sweetie' and 'honey,'" wrote the investigator, Michael Tom. "There were numerous times in which he interrupted and/or spoke over staff and/or other female CIC members/speakers."

The investigator also found that Anderson regularly failed to refer to a CIC staffer, who identifies as transgender, by the correct pronoun. "By failing to use the correct pronoun, Anderson acted unprofessionally and disrespectfully," thereby violating county policy, Tom wrote.

Anderson disagreed with findings he had behaved badly or violated county policy—in fact, he filed a tort claim against the county Sept. 25, 2018, alleging his mistreatment led to "sleeplessness, anxiety and depression."

Nine days after the lockout last June, the County Board of Commissioners voted on the committee's future.

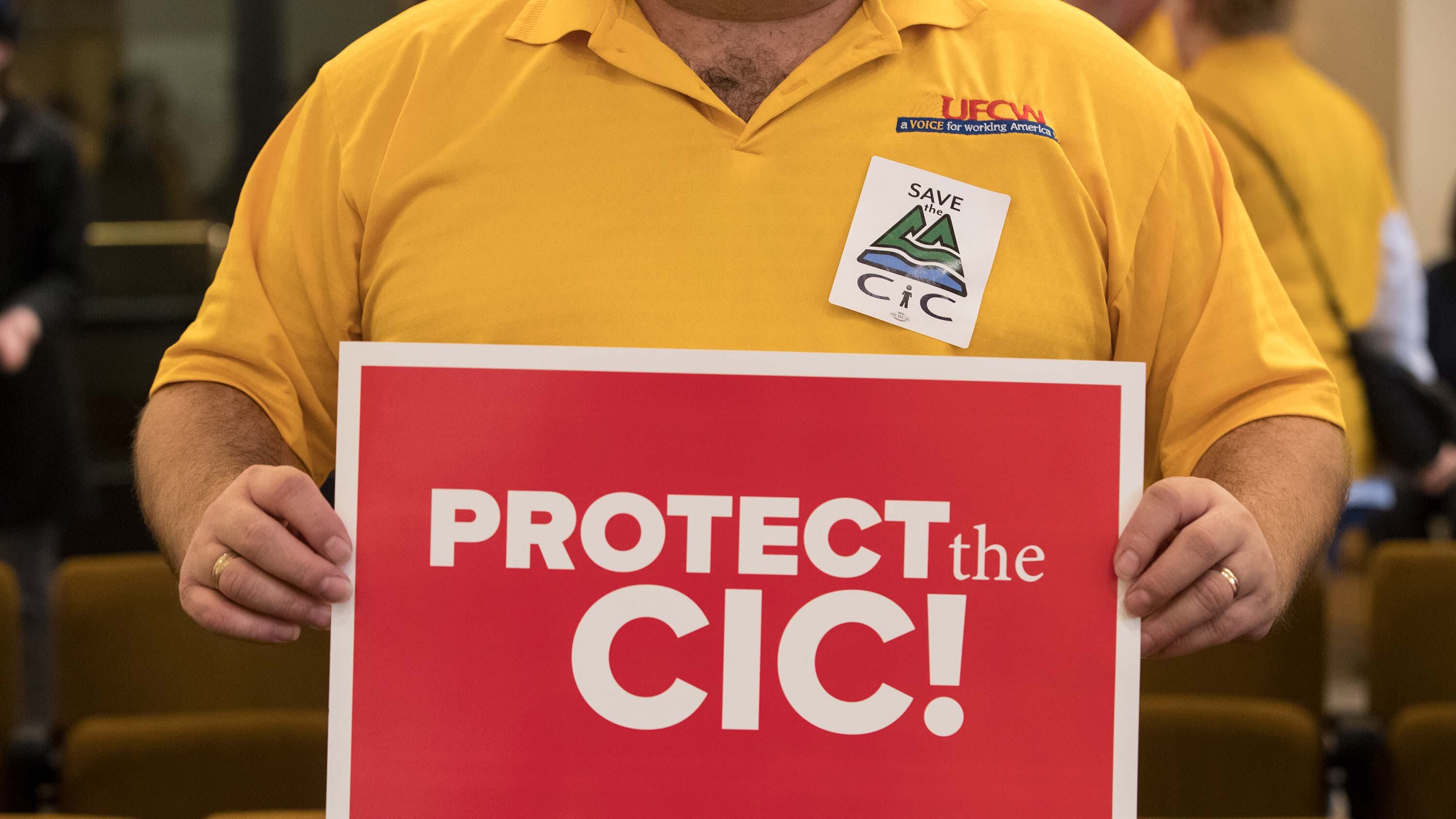

United Food & Commercial Workers Local 555, a union that boasts 25,000 members in Oregon and Southwest Washington, showed up in force at that county board meeting to support Anderson and his colleagues. And although the union doesn't represent county workers or have a business relationship with Multnomah County, the UFCW used social media and a website to support the CIC.

Commissioner Smith, long at odds with Kafoury, cast the sole vote against firing the entire committee and reconstituting the CIC. "I think we're overreaching," Smith said at the time, calling the vote "very extreme." The UFCW encouraged members to send thank-you notes to Smith.

Even after the County Commission voted to dissolve the CIC, the UFCW continued sending gold-shirted members to meetings.

One reason UFCW cared: Longtime UFCW secretary-treasurer Jeff Anderson is Greg Anderson's younger brother.

Jeff Anderson says that even though his union has no business with the county, building a website supporting the CIC and sending UFCW members to county meetings to support his brother's cause are an appropriate use of union resources.

"Greg brought the situation to my attention," Jeff Anderson says, "but our involvement isn't about him—we're speaking truth to power." Jeff Anderson says the UFCW regularly weighs in on matters of public concern. "Our members breathe the air and drink the water where they live and work. We are part of the community."

And they also continued supporting Smith: The union was Smith's largest donor in her 2018 run for the Portland City Council, giving her $54,000.

Jeff Anderson says the contributions were unrelated to Smith's support for Greg Anderson's position. (Smith did not respond to a request for comment.)

Jeff Anderson says he thinks the real issue underlying the dispute is a little-noticed 2016 change in the county charter. That change, approved by voters, gave the CIC a new responsibility: It will choose the members of the next charter review commission.

That may sound wonky, but the charter review commission involves itself in career-changing and -ending questions, such as whether the county sheriff should be elected or appointed (voters said elected, in 2016) or whether term limits for elected county officials should be increased (voters said no the same year).

Jeff Anderson says Kafoury and her fellow commissioners acted to make sure CIC staff reported to them, not to volunteers, and wanted to replace independent thinkers like his brother with committee members who wouldn't make waves.

"It's a power grab," he says.

Kafoury scoffs at that notion. She says she and her colleagues acted after widespread complaints against Greg Anderson and his colleagues.

"We are undertaking a large and serious effort to create an atmosphere of safety, trust and belonging for all county employees," Kafoury says. "I can honestly say the charter review commission issue never crossed my mind, and I don't think it crossed anyone's mind."

The county hopes to re-form a new CIC by the end of February. Meanwhile, a lawsuit filed on behalf of Greg Anderson and his allies is pending in Multnomah County Circuit Court.Even in the hyper-engaged, process-loving world of Portland politics, you'd have to go a long way to find a stranger situation than the implosion of the Citizen Involvement Committee.