WW presents "Distant Voices," a daily video interview for the era of social distancing. Our reporters are asking Portlanders what they're doing during quarantine.

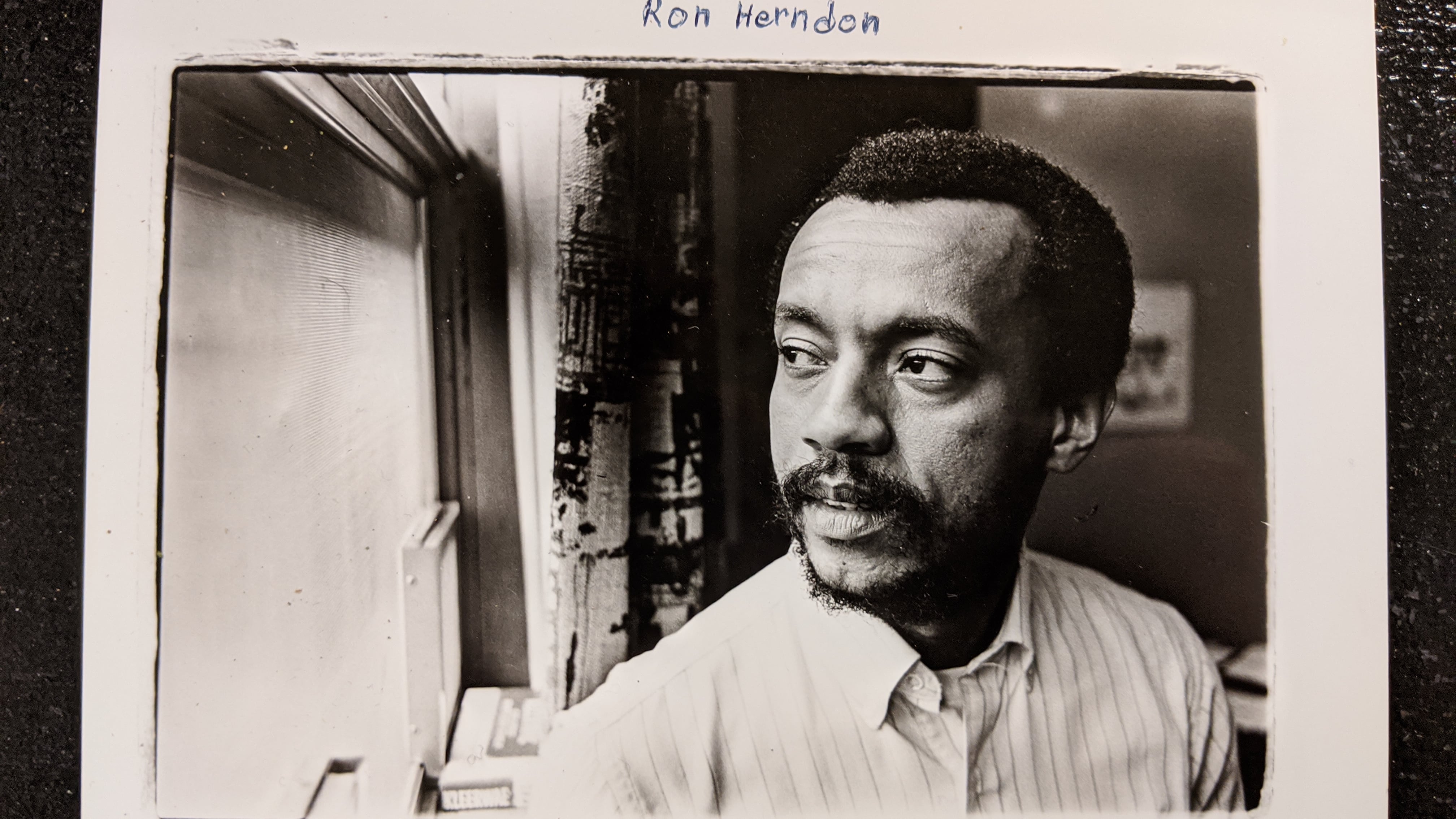

This weekend, Portland will enter its third consecutive week of nightly protests against police killings of black people. Ron Herndon is in his fifth decade.

In 1979, Portland closed predominantly black schools and bused their students to other parts of town.

Herndon led a school boycott that overturned that policy.

In 1981, eight Portland police officers tossed four dead opossums on the doorstep of a black-owned restaurant.

Herndon raised hell and, through his efforts, police oversight became a city policy, however threadbare it may be.

In 1985, white Portland police Officer Gary L. Barbour put an off-duty black security guard named Lloyd "Tony" Stevenson in a deadly chokehold. The day of Stevenson's funeral, a handful of cops sold T-shirts joking about it.

Herndon led the outcry, telling the national press that Oregon's policing was "what you would expect from police hit squads in El Salvador."

So what does Herndon think has changed four decades later? Not much.

"For the average black person, in terms of wealth, it hasn't moved," Herndon says. "Unemployment: same. Health care: not that great. The way that you measure progress for the average black citizen, it's been very, very little change."

Herndon has a record to match that of any figure in Portland's recent civil rights history. Here's a 2004 WW story about Herndon that offers a revealing peek into his accomplishments.

The short version? Born in deeply segregated Coffeyville, Kan., and raised by his grandparents, "Ronnie" Herndon landed in Portland to attend Reed College.

While his day job is director of Albina Head Start, which provides preschool programs for 1,000 low-income kids, protest has never been far from his mind.

In the early 1980s, he organized a protest in which 4,000 black students staged a one-day boycott from school to protest the planned closure of Tubman Middle School. It worked. He publicly pressured Nike to open a store in Northeast Portland and commit to hiring from the neighborhood. It worked. And created a national model.

From our 2004 profile: "Herndon's brains and charm could have taken him just about anywhere, but he's stayed put.…Sometimes appreciated more outside of Portland than at home, he has for more than a decade been the national chairman of the Head Start Association."

He isn't in the streets this week: He's 74 and all too aware that he's vulnerable to COVID-19. But he has remained vocal about everything: the protests and looting; defunding the police; Gov. Kate Brown's lackadaisical response to COVID and people of color; the media's role in all of this; and how the lack of any standards for child care may be more racist than the lack of federal guidelines on police use of force.

In an interview broken into three parts, Herndon talks to WW Editor Mark Zusman about what's different in this moment, and what principles of activism remain the same.

In the first clip, Herndon discusses how things have and have not changed for blacks in Portland over the past 40-plus years. (See above.)

In the second segment, Herndon says the current protests must expand the scope of their concerns beyond policing. And he describes how Oregon leaders failed black people as COVID descended on the state.

In the third part of our interview, Herndon identifies who should next be held accountable for destroying Portland black communities.