COVID-19 is currently spreading faster in Oregon than in all but one other state, says one group of experts.

As of April 12, according to mathematical modeling by a team of Harvard, Yale and Stanford medical experts, the reproduction rate in Oregon is 1.39—meaning every 100 infected Oregonians are infecting an average of 139 others. Any rate above 1.0 means the number of cases is growing.

That's a faster reproduction rate than at any time since the surge in cases last fall. (The Oregon Health Authority's projections put the case reproduction rate lower.)

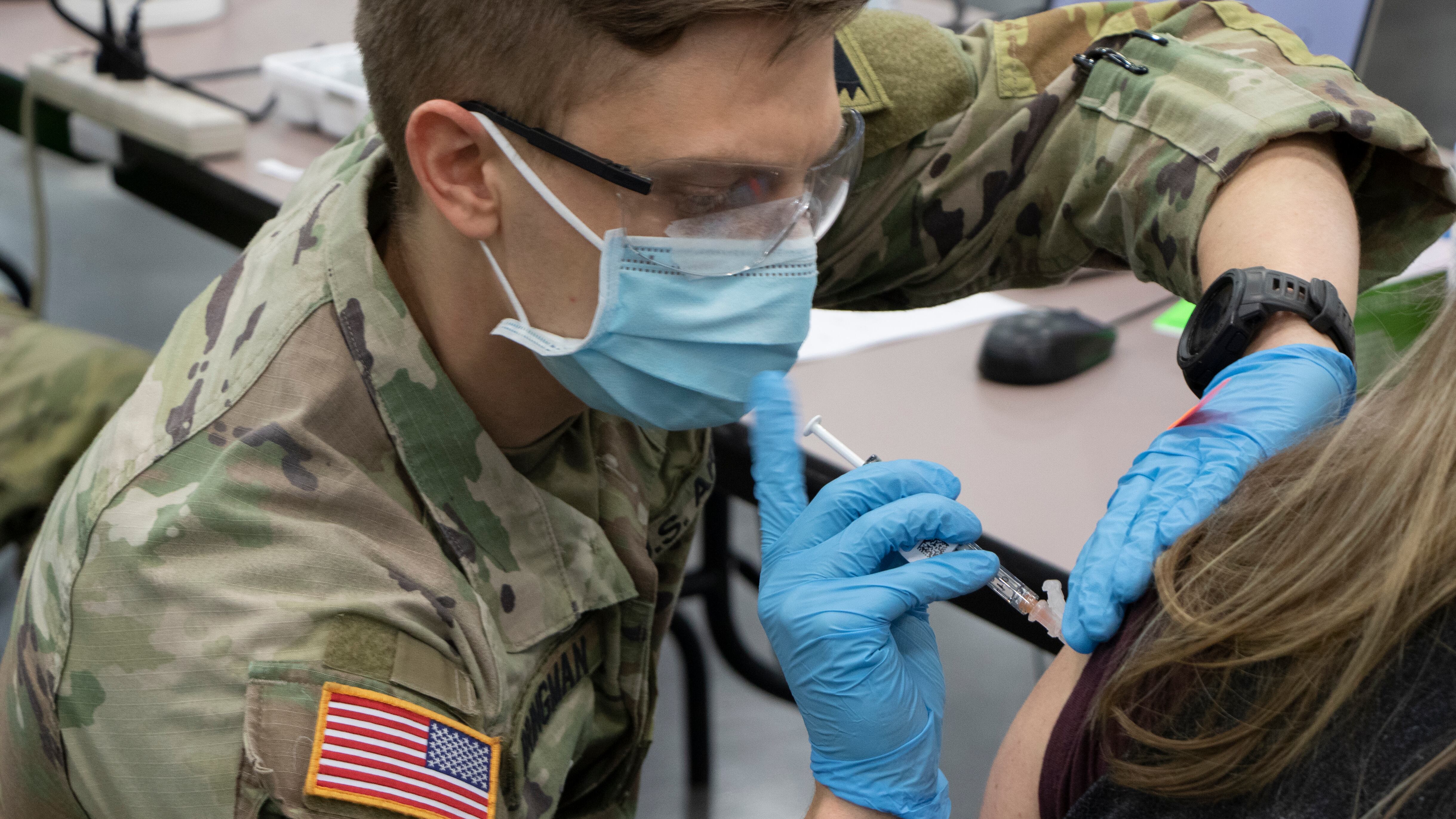

The growth is happening even as the state's vaccination rate is rapidly increasing. In Oregon, more than 1 in 5 people are fully vaccinated. And 43.5% of the Oregon population over 16 has at least one dose, according to The Washington Post.

Yet cases are spreading so quickly in part because of an increase in variants of the virus that are more contagious. An estimated 12% of cases in Oregon are from California variants that are estimated to be 20% more contagious than the original coronavirus, OHA says.

The good news, as OHA director Pat Allen told state lawmakers last week, is that the West Coast is experiencing a different pandemic right now because Oregon, Washington and California are impacted by the California variant. In the rest of the nation, the U.K. variant—which is 50% more contagious—is the most common strain in the country. In Oregon, it's less than 1.4% of the specimens that have been sequenced.

Experts could foresee a potential spike in cases even as vaccines were arriving, and told state leaders as much. For two months, they've warned that vaccinations are in a race against variants. State health officials had a plan—and they didn't stick to it.

THE SAFETY NET

During the fall surge, Oregon put in place a system to adjust risk levels based on county COVID case rates. If an Oregon county faced extreme risk based on case counts, gyms would have to close and restaurants and bars could no longer offer indoor dining. The system was designed to operate at one remove from the political considerations Gov. Kate Brown would have to make. It meant she could point to the metrics and not have to make a new decision on lockdowns every week.

For a WW story Feb. 24, Brown's health advisers, Tina Edlund and Connie Seeley, were asked about the risk posed by the rise of variants in the U.S. and projections that Oregon could see a fourth wave before summer.

"If we were to see cases go up," Edlund told WW, "as soon as we see them cross that threshold for extreme risk, those restrictions kick into place."

THE REVERSAL

Brown backed off those guide rails in two ways.

On March 4, Brown announced that any county that had just moved to a lower risk level would receive a two-week grace period before it could be moved back to a higher risk level. In other words, if a county's cases spiked, it would be granted an extra two weeks before being placed back under restrictions.

On April 6, Brown announced a new metric: No county would move to extreme risk unless there were 300 COVID-19 patients in hospital beds statewide, as well as a 15% increase in the seven-day average for hospitalizations. (An Oregon Health & Science University projection April 1 suggests Oregon may never hit that number if vaccinations continue to increase.) In other words, unless the state as a whole was running out of hospital beds, no county would be fully locked down again.

THE IMPACT

The two changes combined prevented Baker, Columbia, Josephine, Klamath and Tillamook counties from closing down bars and gyms last week. Three other lower-risk counties—Lane, Polk and Yamhill—also did not see their status change, which means a two-week delay on limiting restaurant and gym capacity even though cases are spiking. New changes in risk levels don't get announced until April 20—and take effect April 23.

THE REACTION

Rep. Lisa Reynolds (D-Portland), a pediatrician, raised questions about the decision not to impose restrictions.

"The priority needs to be reopening schools," Reynolds says, "and if that means we have to continually resume tighter restrictions to bring down community rates, then that's what we should do."

Multnomah County Commissioner Sharon Meieran, an emergency room doctor, agrees. "The one thing we can't do is close our eyes and hope the problem goes away in the light of changing circumstances," she says. "It really worries me."

Brown's office says the county risk system remains in effect. "The risk level framework establishes significant but sustainable restrictions on businesses and activities to protect Oregonians when COVID-19 metrics spike," says spokesman Charles Boyle. He cites one difference between now and the November surge: Vaccines now protect some of the most vulnerable people. "Those restrictions are meant to save lives, by preserving hospital system and health care worker capacity to treat the most serious cases."