When Martin Knowles moved into Kenton in the spring of 2010, he knew Portland International Raceway was just a half-mile from his house.

Before he and his wife bought their home, Knowles, 42, tried to understand how loud the racetrack might be. “On their website,” he says, “they claim the majority of days it’s not audible at any point in the neighborhood.”

For Knowles, who made $18 an hour at nearby Swan Island, Kenton was a good, affordable neighborhood.

And for the first month, as the couple settled into their new house, they didn’t hear a sound.

Then the races started. “I was like, ‘Holy crap!’” Knowles says.

It was Knowles’ welcome to PIR, the closest major road-racing track to a residential neighborhood in the U.S. Everything from Indy cars to motocross bikes to historic sports cars race on the flat track in front of grandstands that have held as many as 40,000 spectators.

Depending on the size of the internal combustion engines running that day, Kenton residents have described the noise as a high-pitched whine, like a swarm of wasps, or the sound of an engine revving that comes and goes in waves, like a neighbor with a gas-powered leaf blower.

“I can’t get away from it,” says Nini Liedman, 34, who has lived in Kenton for eight years. Liedman says noise from the racetrack has started to affect her mental health. “I can hear it through headphones, I can hear it through earplugs, I can hear it when I close all my windows,” she says.

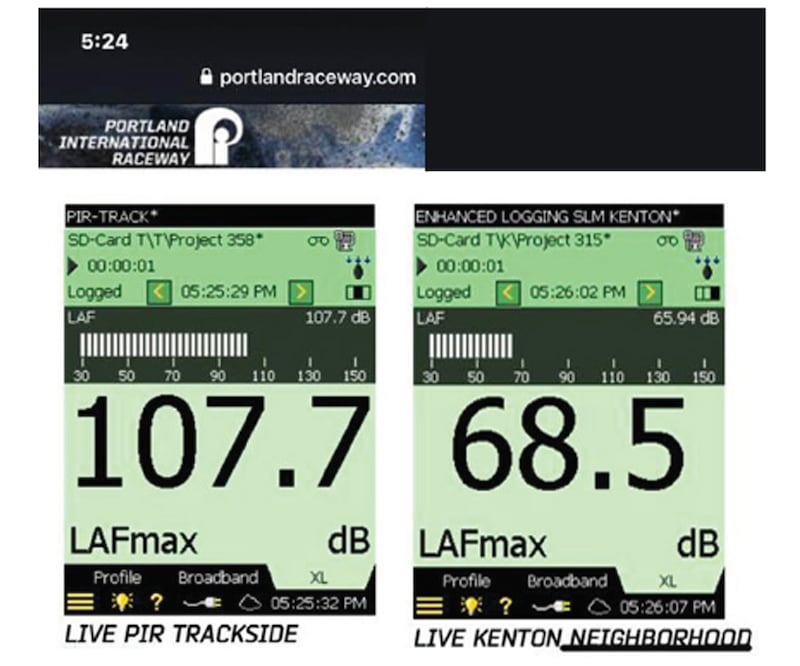

In fact, according to residents’ readings of a noise control monitor placed in the neighborhood six years ago, the racetrack has exceeded the legal limit for noise in the neighborhood—65 decibels—hundreds of times. “I’ve reported violations at least once a week for the entire summer for six years,” says Knowles.

Such violations have been reported to the city of Portland, which, according to more than a dozen Kenton residents, has done little to nothing about the rule breaking.

Some think the reason is simple. It’s because the owner of the racetrack is the city of Portland.

That’s right—Portland is one of just two local governments in the United States that own racetracks. The other is Monterey County, Calif., whose parks department owns Laguna Seca Raceway near Salinas.

Opened in 1961 on the remains of Vanport’s flooded streets, PIR has been hosting races in North Portland, on the edge of the Kenton neighborhood, for 60 years this summer.

“I’ve always felt that the city would be harder on PIR if they didn’t own it,” says Ryan Pittel, a board member of the Kenton Neighborhood Association.

Racers often describe PIR as unique. They’re not referring to the track itself, which is a pretty typical 2-mile loop. It’s the location.

Mark Scholz, a local racing enthusiast who regularly drives his Maserati Gran Turismo to the racetrack from his home in Southwest Portland, says PIR is the only racetrack where you can go race for the day and be back home in time for dinner. “It’s an ability to indulge your passion in motorsports without being far outside the city limits,” he says.

In a recent promotion by the Sports Car Club of America, PIR is described as being “a stone’s throw from downtown Portland.” While that might be an exaggeration, it is a five-minute stroll across the Columbia Slough from Kenton, a neighborhood of over 8,000 that historically has been home to low-income and diverse populations.

PIR hosts events nearly every day of the summer. And many of them are a trial to Knowles and his neighbors, who say the noise from the track pollutes their lives and causes them to dread summer.

For many people who live near the track, the issue isn’t just the volume. It’s their growing belief that the city won’t enforce its own noise ordinance at PIR—violating a promise it made to the Kenton community more than 30 years ago.

In 1976, Portland passed its first noise ordinance. Immediately, that meant the city was violating its own law because the races at PIR routinely exceeded the new noise limit.

A decade of conflict between the city and North Portland neighborhood associations ensued until an uneasy agreement was finally reached in 1989: The neighborhood associations would stop fighting the track over noise issues, and the track, in exchange, would limit its loudest races to four events a year, would put a portion of ticket sales into a trust fund for the neighborhood associations, and would agree to honor city noise levels the rest of the time.

The noise code, then and now, is clear: 65 decibels is the maximum noise allowed for residential neighborhoods. According to the agreement, limiting the noise from cars on the track to 105 decibels would equate to no more than 65 decibels at the nearest home.

That 65-decibel sound limit is the number all of this struggle turns on.

PIR, run by Portland Parks & Recreation, claims that regular track activities don’t exceed 65 decibels. For the past 11 years, Knowles has been documenting the opposite.

“Their website is saying I shouldn’t be hearing it,” he says, “but it was really, really loud.”

Pittel of the neighborhood association agrees. “They tend to go over it on almost a daily basis.”

For a long time, it was simply the neighbors’ word against the city’s. Finally, in 2015, responding to pressure from the neighborhood association and the city’s noise control program, the parks bureau installed a sound monitor in Kenton. “We pushed for about a decade to have a meter before it was put in place,” says Portland noise control officer Paul van Orden.

Knowles and his neighbors showed WW screenshots of the meter indicating violations of the city’s noise limits 18 times this summer alone. When Knowles sent those images to the city, he says, he was ignored.

Most of the two dozen Kenton residents WW interviewed told a similar story: They complained via phone or email, sometimes repeatedly, and never heard back or, if they did, were told it wasn’t actually a violation.

Portland Parks & Recreation received 61 complaints about noise at PIR during the 2018 and 2019 racing seasons, of which six were found to be valid, says parks spokesman Mark Ross.

He contends that few of the neighborhood annoyances were caused by the racetrack. “Nearly all the temporary noise ‘spikes’ were caused NOT by races at PIR,” Ross writes, “but by other sources such as trucks on nearby roads or boulevards, dogs, lawnmowers, crow calls, kids playing, or train horns.”

But, it turns out, the city didn’t need Knowles’ screenshots, or even its own meter, to tell how bad the noise was. Seven years before installing the neighborhood noise monitor, the city commissioned a study of noise pollution in North Portland.

What that study found was that noise from the raceway probably exceeded 65 decibels in a significant portion of Kenton. The city’s modeling indicated that noise levels at the edge of Kenton during a typical race might even reach 75 decibels. The report concluded that trackside noise might need to be reduced to comply with the noise code and maintain healthy noise levels.

The report was never formally released, though WW obtained a draft copy from the Kenton Neighborhood Association. When asked why the report hadn’t been released, the city’s noise office said it was inconclusive and required more work to link noise from the track to the sounds heard in Kenton, but that the economic crash of 2008 derailed further study. “The noise office has requested over the years that further funding be provided to assess and mitigate sound levels, which will require a substantial investment by City Council,” wrote noise official Kareen Perkins.

Supporters of the racetrack point out that Kenton is already one of the most noise-polluted neighborhoods in the city—falling as it does near flight paths for Portland International Airport, next to Interstate 5, and alongside a well-used railroad track—and the report agreed.

But for noise officer van Orden, that doesn’t diminish the scale of the PIR’s roar: “As an environmental scientist, I felt that there was a clear issue at the racetrack that we could actually address because it’s a city-owned facility.”

On a recent Wednesday evening at the track, a sparse crowd of spectators drink cans of Coors Light as a line of cars ranging from street-legal family sedans to purpose-built dragsters wait their turn to race down the track.

John Waleske, 72, watches as two cars nose their way to the starting line. The drivers gun their engines and spin their tires. “I used to work with that guy at the Camas paper mill,” Waleske says, nodding toward a racer in the line.

For nearly 50 years, Waleske has been coming to the drag races. He used to race his own car—a 1965 Corvette—but now he just comes to watch.

The racetrack is not a cash cow for City Hall. The track itself generates $2 million in annual revenue, just enough to cover operational costs. There is a larger economic benefit, to be sure: The city estimates track visitors spend $35 million a year on things like hotels and food. But because the track is owned by the city, it is not on the property tax rolls.

And many of the events are private track days for enthusiasts of Porsches, BMWs or the Ferrari GT3. Such events still make noise but aren’t open to the public.

“You go by there on a weekday and there’s nobody in the stands. It’s just guys racing around,” explained the neighborhood association’s Pittel.

City officials who run the parks bureau don’t seem to want to talk about the racetrack. All of WW’s interview requests to Portland Parks & Recreation officials and PIR staff were declined.

We asked City Commissioner Carmen Rubio, who has overseen Portland Parks & Recreation since January, if her bureau should be in the business of operating a motorsports racetrack. Her office issued a statement: “Portlanders want a variety of recreational spaces, and providing this variety within resource constraints can be challenging.”

WW asked again: What was Rubio’s response to neighbors who say the racetrack is too loud?

Rubio said she hadn’t heard from many of them. “The issues being raised are issues deserving of attention,” she added. “The good thing about being a newly elected official is that I can revisit decisions that transpired before I took office with fresh eyes. PIR is committed to being a good neighbor, and I would love to hear more from Kenton neighbors who believe it is falling short.

The track also lies in the legislative district of House Speaker Tina Kotek (D-Portland), one of the most powerful elected officials in the state, who is mulling a run for governor next year. She has occasionally taken an interest in PIR, pressuring the city to warn patrons of exposure to lead because of the track’s regular use of leaded gasoline.

But Kotek tells WW she has always ferried complaints about the track to City Hall.

“I can certainly empathize,” she says, “as noise from the track can sound like a hive of bees on days when the sound carries at my home in North Portland. The city has the authority to address recurring noise violations, and it’s disappointing to hear they have been less than responsive on this issue.”

For now, Marty Knowles still emails the city noise office, but he’s not hopeful anything is going to change. Instead, he and his wife installed triple-pane windows, which cost them nearly $10,000. “It took me seven years to pay them off.”

The last time WW spoke to Knowles, he invited us to his house. We sat in his backyard, on big Adirondack chairs in the midst of kid’s bikes and an inflatable pool. When asked why he thought all of his efforts had resulted in nothing, Knowles said he didn’t know: “The only reason I can see for this going on this long is that nobody cares about Kenton.”

Anyway, that’s more or less what he said. As he spoke, his voice was drowned out by the drone of cars racing at the track.

A Fine Whine

So how loud is 75 decibels anyway? Noise is complicated. First off, the decibel scale is not linear, it’s logarithmic—which means 75 decibels sounds twice as loud as the legal limit of 65 decibels.

The World Health Organization and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention say that noise levels above 70 decibels interrupt conversation, can cause elevated blood pressure and other health conditions, and may even damage hearing.

And it’s not just noise levels, it’s also the quality of the noise. How long does it last? How high pitched is it?

For Nini Liedman, the continuous nature of the noise emanating from Portland International Raceway is what makes it so unbearable. She says she can’t have a conversation in her garden when the cars are racing. “If a train comes, you would just stop [talking] and then you would just finish after the train goes.”

Pittel says it’s the pitch of the cars that makes your ears pick it up: “It’s that higher whine.”

Other racetracks have had to deal with noise complaints from neighbors—some by limiting the noise and some by going out of business.

Two notable examples, Bridgehampton Race Circuit on Long Island and Riverside International Raceway in California, were originally built in the countryside but in the path of urban growth and were ultimately shut down over noise issues: Bridgehampton is now a golf course, and Riverside is a shopping mall. EMMA PATTEE and STUART HENIGSON.

Noise Is Complicated. Lead Isn’t.

Unbeknownst to many Kenton residents, Portland Parks & Recreation still allows the use of leaded gasoline at Portland International Raceway, despite the fact that exposure to lead is poisonous to children.

“I was shocked,” said Linda Wysong, who only recently found out about PIR’s lead use after living in Kenton for two years. “The last thing we want to do for either people or animals is increase the lead in the air.”

Lead exposure has been shown to cause neurological disorders and brain damage in kids as well as hearing and speech problems, a concerning fact for Kenton parents whose children live downwind from the track. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention specifies there is “no safe blood lead level in children.”

While PIR claims that its only responsibility is to inform track visitors of lead use, Wysong points out that “air doesn’t stop at the fence line.”

Oregon House Speaker Tina Kotek, whose office pushed PIR to install signage warning track visitors of lead use, says she couldn’t get the parks bureau to prohibit it altogether. “My understanding,” she tells WW, “is that the city of Portland was supposed to be further studying the issue.” EMMA PATTEE and STUART HENIGSON.