Way up in North Portland, not far from the Jubitz Truck Stop, sits a new Portland neighborhood whose homes you won’t find on any map.

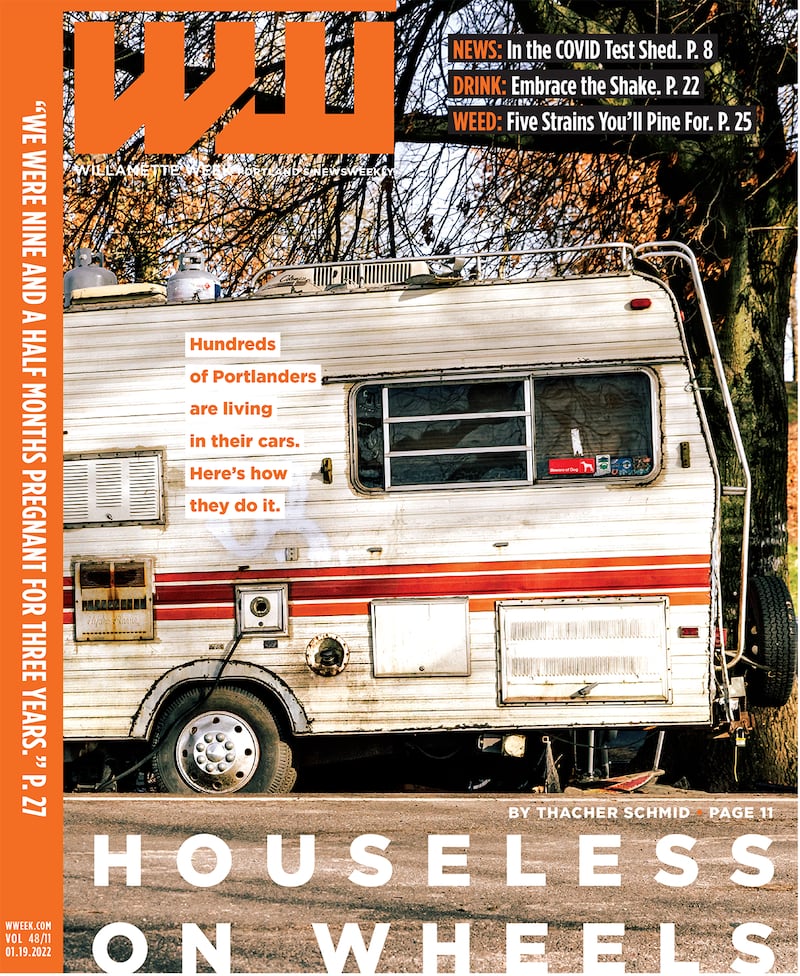

Along North Union Court, on a recent rainy day, dozens of decaying RVs, cars and campers lined the road, alongside tents that appeared to be floating in puddles.

The scent of chocolate from a nearby bakery mixed with the smell of cigarette smoke, gasoline, urine and feces. Burn piles, discarded furniture, and orange caps from hypodermic syringes dotted the landscape. Traffic noise and roaring gas generators made conversation difficult.

About 30 people call this swath of city-owned Delta Park home. Some sleep in tents, but most reside in vehicles ranging from subcompact cars to full-size RVs.

This encampment is illegal, but city officials look the other way.

On this Thursday, outside a vintage RV, a humming generator powered lights and a TV inside. The resident is a man who gave his name as Chris who says he was sober 11 years, then relapsed at the start of the pandemic. Meth is his drug of choice. Within months of relapsing, he lost his job, then his housing.

Life is a challenge in an RV, Chris admits, but better than sleeping in a tent. “The wind just rips through these fucking tents,” he says. “It’s brutal.”

In Portland, the number of people living in vehicles is growing.

Ben Sand, a former board member of A Home for Everyone, which provides homeless services in Multnomah County, says local vehicle residency is “metastasizing.”

Sara Rankin, director of Seattle University School of Law’s Homeless Rights Advocacy Project, says people living in vehicles is emerging as the fastest-growing homeless subpopulation in the U.S. By some estimates, vehicle residents comprise more than a third of unhoused people in West Coast cities.

On paper, it’s illegal to live in your vehicle in Portland. But city planner Eric Engstrom says “active” enforcement is not happening right now for three reasons: the Martin v. Boise decision, which says officials can’t sweep houseless people without corresponding shelter space; federal COVID safety guidelines; and because “it’s unpopular and not super effective.”

In many cases, people who live in their vehicles are hidden in plain sight, blending into residential street parking with few signs they’re there besides window shades.

In 2019, the most recent year Multnomah County counted unhoused people, vehicle residents did not appear in official statistics (see “But Who’s Counting?” below).

That failure to report a number reflects the wider inattention given to people living in cars and other vehicles.

Even as the numbers keep growing, Portland and Multnomah County officials have repeatedly failed to create a program or location where people living in vehicles can legally park overnight.

“Vehicle residency is a hidden crisis in plain sight,” Rankin says—one both missing from official data and hidden by “thin tin.” It’s reaching “an unprecedented pitch,” she adds, and the result “is not only inhumane, it amounts to a costly rotating door that imposes significant fiscal burdens on cities.”

Vehicle residency has nearly century-old roots, ranging from “Okies” in car homes on Route 66 to Instagram influencers living glam existences in tricked-out vans.

But what’s happening on Portland’s margins is a far cry from #vanlife.

For unhoused people, the logic of the choice to move into a vehicle is clear. Vehicles are often the best option for those displaced from a very expensive housing market, says Tristia Bauman of the National Homelessness Law Center. (Portland is the third-highest metro area in the U.S. for cost-of-living increases.)

What’s it like to live in a small metal box designed for transportation? In five interviews, vehicle residents suggest it’s grueling.

Moving is stressful. Vehicle dwellers do it constantly. City codes prohibit “camping,” including “any vehicle or part thereof” on public property or roadways. So many vehicle residents just drive around, as Lee, a man living in an aging, graffitied Chevy Astro, says he did for months before settling in Northeast Portland near Interstate 84. (Lee declined to share his last name. For this story, WW didn’t require vehicle residents to give last names, and some of their assertions could not be verified.)

Wheels can be a way of avoiding enforcement actions in Portland, even without driving away. Lee notes recent city sweeps of people living in tents near where he parks allowed vehicle residents to remain. He calls the life a “limbo zone” but appreciates such advantages.

The zones where people often settle, near freeways and airports, are noisy. “We’re always screaming at each other,” says Genevieve Nunez, who lives in an RV at Delta Park.

Hygiene is a constant worry, Nunez adds. She relies on baby wipes. “Relationships with your husband, whatever,” she says. “Being a female, you have to.” She showers at the Jubitz Truck Stop, which increased its price from $15 to $25 in June.

Rats can infest a vehicle’s structure. Moisture is a constant battle this time of year. “You have to move around your situation,” Lee says, restructuring the interior so mold can’t grow.

Gas-powered generators or car batteries provide electricity. Lee’s generator failed, so he depends on two car batteries, taking one to Batteries Plus to recharge while the other powers his home.

Lee and many others use inverters—which convert direct current to alternating current—to charge their cellphones and power Wi-Fi hot spots to access the internet or stream video.

Life in a vehicle is always a challenge. Sometimes it’s an existential threat.

For Sara Kuust and Jake Blackburn, a traumatizing moment living in a vehicle last year merged the challenge of going to the bathroom with the affection and companionship provided by animals.

Last January, after losing their place at a Portland hotel, they moved into the couple’s 1999 Chevy Blazer with a friend and four kittens named Baby Girl, Earl, Li’l Bit and Spaz. They kept a litter box on top of possessions stacked “like Tetris” in the back.

Kuust was pregnant and “had been holding my pee a lot” due to the inaccessibility of restrooms. Her favorite kitten, Baby Girl, was purring in her lap in a big box store parking lot when the unthinkable happened: She had a miscarriage. No doctor, no hospital: just her car.

Vehicle residents grapple with other dangers, including addiction and fires. Portland Fire & Rescue spokesman Lt. Rich Tyler says there were 29 houselessness-related RV fires last year—more than double the 13 in 2020, up from three in 2019.

Two RV dwellers died in fires in the past three years, the agency says. There were 1,516 vehicle fires in the four years from 2018 to 2021, a big increase over the previous seven years.

At North Union Court and other local vehicle residency communities, gasoline, propane, cigarettes, stoves, open flames and intoxication can form a volatile mix.

Last year, Chris says, he put gasoline into a container that normally held water, forgetting to tell his partner before going to sleep.

“So she fills the pan up—I think she was boiling water to do dishes,” Chris recalls. “She freaking lights the burner and whoosh! I wake up to her screaming and I see a big flame…I levitated to the front of this fucking trailer, grabbed the fire extinguisher and put it out. It [went up] so fast it was mind-boggling.”

Drugs numb the pain but can lead to addiction, or overdose.

Methamphetamine was the drug of choice for residents of another large vehicle residency community on Northeast 33rd Avenue in 2020. At Delta Park, Nunez says, “it’s heroin and the blues”—blue fentanyl pills. Heroin is her drug of choice. “We usually just fall asleep on the bed, sitting up or nodding out,” Nunez says.

Chris claims to have saved four lives in the area by keeping naloxone, a nasal spray that can halt an opioid overdose, in his RV. “Everybody knows to come here if they need Narcan,” he says.

Since the passage of Measure 110 in 2020, possession of most drugs for personal use has been decriminalized in a state that is perennially among the worst in the nation at addressing substance abuse and mental health disorders in rankings compiled by Mental Health America. “We’re always at the bottom,” says Portland Housing Commissioner Dan Ryan.

In the wake of drug decriminalization, Portland Police Bureau Sgt. Jennifer Butcher says, police treat vehicle residents in possession of drugs the same as people inside a dwelling—deprioritizing such calls as long as users are not driving. Police say they see an increase in vehicle residency and a corresponding rise in calls for service to those areas.

Nunez claims two people have died at the Delta Park encampment so far this winter. Those deaths could not be verified, but Portland police say they do have a record of two death investigation calls in 2021 at the location.

Many cities have designated “safe parking” programs for people living in vehicles. Unlike Beaverton, Vancouver, Wash., and 43 other U.S. cities, however, Portland does not.

Late last year, Ryan’s office and Metro halted almost a year’s worth of talks to put one at the Expo Center. Officials blame the difficulty of siting a lot near wetlands.

“Portland does need to move on this,” Ryan says. “When you’re driving around town, you can just see that there are a lot of people sleeping in their vehicles.”

Mayor Ted Wheeler tells WW that the housing crisis remains a top priority—including Portlanders living in vehicles.

“Trying to accurately understand just how many people are currently living out of their vehicles in Portland is a difficult and complicated task,” Wheeler says. “We know that there are far too many. I fully support the work Commissioner Ryan and his team are doing in developing the Safe Park Program, where Portlanders living out of their vehicles can do so safely and be provided sanitation stations, mental health and living assistance.”

Across the Columbia River, in the metro region’s second-largest city of Vancouver, Wash., the situation is different. Nine churches currently host five to 10 vehicle homes apiece, Mayor Anne McEnerny-Ogle says, and the city offers a program for “30-plus large vehicles” at the Evergreen Transit Center—in total, about 100 spaces.

“It’s all quiet, calm, supervised,” she says. Officials are seeking a second RV site.

There have been cries of “Send them back to Portland,” she says. But, McEnerny-Ogle says, Vancouver has held itself accountable. “These are our own.”

McEnerny-Ogle offered a thought for Portland and Multnomah County. “Just start small,” she suggests. “It’s like losing weight. Take the big problem, chunk it down into smaller bites.”

The abandoned Expo Center plans were not the first failure to create a designated vehicle residency space in Portland.

In 2018, the Joint Office of Homeless Services allocated $100,000 to Catholic Charities of Oregon for the 2018-19 fiscal year for a “minimum 2,956 nights” so vehicles could park overnight in local faith-based organizations’ parking lots.

There’s no evidence the program ever opened a parking site.

The local response to the church parking idea was “tentative” and “hesitant,” Joint Office spokesman Denis Theriault notes. Catholic Charities of Oregon declined to comment.

Laura Purkey, a St. Johns resident who assists people living in their vehicles with food and services through the volunteer program Free Hot Soup, says local governments aren’t acting with enough urgency.

“Clearly, it’s not enough,” she says. “It’s just a Band-Aid over a gaping wound. It just doesn’t seem right to me, for this kind of continual crisis, that we don’t have something that’s more organized to kind of step in. Like [Federal Emergency Management Agency]. Why don’t we have an emergency response? Why are we just letting this continue on and on?”

The failure of both county and city officials to find solutions has contributed to public discontent.

Local business leaders, and their new 501(c)(4) organization, People for Portland—funded by Columbia Sportswear CEO Tim Boyle and Harsch Investment Properties president Jordan Schnitzer, among others—have made homelessness their central issue.

This week, the group released results of a survey finding that three-quarters of likely voters in the metro area believe city and county spending on homelessness has been ineffective. Sixty-three percent support a safe parking lot at the Expo Center, a project Commissioner Ryan has now abandoned.

But what do vehicle residents want? Housing stability, yes—but also economic stability. All five of those interviewed for this story work and say they’ve lost income during the pandemic. Keeping a job while living in a vehicle, they say, gets harder over time. “It just snowballs on you once you get out here,” Lee says.

A lack of income is only one barrier to moving from a vehicle back into conventional housing. For many, lack of identification, felony records and poor credit can be formidable hurdles as well.

“There’s lists,” Nunez says. “You got to have ID. You got to have this, you got to have that.” Her criminal record is no longer as big a barrier since drug decriminalization, she says—but it still interferes with a lot of opportunities.

Those best positioned to help unhoused people overcome such barriers, or connect agencies and the streets, are social services professionals. But vehicle residents and local volunteers say they almost never see county-contracted social service workers—just enforcement and cleanup crews.

“Nobody comes out,” Lee says. “The only time they come out is Rapid Response [Bio Clean, a cleanup company that conducts sweeps].”

So local vehicle residents often place hope in themselves. “There ain’t no way out,” Lee says. “Just got to work.” Nunez has offers to stay with family but says they’re struggling too, and she’d feel like a burden on them, “another mouth to feed, more laundry, more bills.”

Chris is contemplating sobriety, thinking back to when he made $80,000 a year and lived in an apartment in Tigard.

“When I do start thinking about normality and routine, I want that back,” he says. “But it’s easier to say than to get it back.” He’s not interested in an apartment, though—he’s 36 and has been renting his whole life. “I need something to own,” he says. He claims he and his partner have “stacked up” $11,000 toward a down payment on a house.

Having learned from a previous mistake, he isn’t keeping it in cash inside a safe in his RV.

But Who’s Counting?

Clues hint at how many people live in their vehicles on the streets of Portland.

How many people are living in their vehicles in Portland? It’s not a figure that local agencies have tracked closely, but clues exist.

Federal officials require local authorities to count the number of people experiencing homelessness on a single night every two years to ensure “continued eligibility for state and federal funding.” Locally, the Joint Office of Homeless Services sponsors a street or “point in time” count, and Multnomah County does a shelter count.

The 2021 PITC was canceled due to COVID. So the most recent count was made in January 2019.

But the 2019 count did not report how many people were sleeping in vehicles.

After questions from WW, county officials said they did know the number: 310 individuals. By comparison, the 2017 PITC reported 257 households, including 41 “families with children,” but an unknown number of individuals sleeping in vehicles.

The lack of reporting of vehicle residency in 2019 is confusing because sleeping location has for years been the first question on the PITC survey, which is usually completed by the “head of household.”

“It’s a good question: What the fuck happened to question number one?” says Marisa Zapata, director of Portland State University’s Homelessness Research & Action Collaborative. (PSU is handling this year’s count, as in 2017 and 2019, but Zapata was not involved in the 2019 PITC.)

The Joint Office of Homeless Services is in charge of the count. Its spokesman, Denis Theriault, says 310 individuals were counted in 2019 but not reported due to a “simple oversight.” He declined to elaborate, other than to note that the 2019 report was the first to include an interactive dashboard.

The PITC is one of several data points that help direct significant sums of federal dollars through the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s complicated and opaque “continuum of care” system. So getting the fullest possible picture of who’s living in cars comes with significant stakes.

Estimates of total federal allocations for homeless services since the CARES Act fall between $12.5 billion and $17 billion. That’s on top of local funding, including the 2020 Metro homeless services measure, which will provide the Joint Office with nearly $1 billion in the coming decade.

Numbers tallied in the three years since the last official count suggest vehicle residency has grown significantly.

In March 2020, when the pandemic hit, reports of people living in vehicles to the city’s One Point of Contact system tripled, from around 100 to 389—then doubled the next month, to 633. Last month, it hit 1,093.

Some believe the true scope of the vehicle residency problem is much larger than local officials acknowledge. Benji Vuong, who helps distribute food and supplies to people living in vehicles for the group Free Hot Soup, estimates there are 5,000 vehicle residents in the metro area.

This year’s point in time count is scheduled to begin Jan. 26. (To volunteer, email pointintime@pdx.edu.)

PSU’s Zapata says she doesn’t see what’s gained by knowing how many people are in vehicles versus tents: “What would you gain by having that split? Is there a meaningful difference there that would matter to solving homelessness?”

She acknowledges, however, that vehicle residency remains a gray area.

“The stuff on wheels makes me very nervous,” she says. “I think it’s actually quite complicated. How people use RVs to live and survive in, not as recreation—that is not well understood.”

Nomads by the Numbers

310

People residing in vehicles in Multnomah County on a single night, as recorded in the last point in time count, conducted in January 2019. In the 2017 count, there were 257 households but an unknown number of individuals. (In 2011, 150 individual vehicle residents were counted.)

1,093

Reports of people living in vehicles received by the city of Portland in a single week in December. That’s the highest number of complaints recorded by the Urban Camping Impact Reduction Program in the past two years.

2,299

Complaints received by the Portland Bureau of Transportation about people living in vehicles on city streets in 2021. Those complaints declined steeply from 3,750 and 3,873 in 2020 and 2019, respectively. “We think the numbers from 2019 to 2021 are going down not because there are fewer people living in vehicles, but because members of the public are less likely to call now,” PBOT spokesman Dylan Rivera says.

29

RV fires in 2021 that Portland Fire & Rescue logged as “homeless related.” That’s double the 13 such fires recorded in 2020. In 2019, there were three.

$780,000

American Rescue Plan funds allocated to RVP3 through the end of 2024. It began as a pilot program in March 2021 and was recently funded for three years.

999

RVs served by RVP3 since the program started.

6

Locations visited regularly by both PBOT’s vehicle inspection team and BES graywater contractors, because city officials know inhabited RVs are parked there. These sites include Delta Park, camps along Interstate 205 between Southeast Powell Boulevard and Flavel Street, Northeast 33rd Avenue near Marine Drive, and the Big Four Corners Natural Area near Portland International Airport.

16,000

Gallons of graywater reclaimed from RVs parked on city streets by the Bureau of Environmental Services’ new RV Pollution Prevention Program, or RVP3, according to spokeswoman Diane Dulken.

38,000

Estimate of people experiencing houselessness in the tri-county area in 2017, according to Marisa Zapata, director of Portland State University’s Homelessness Research & Action Collaborative. This number is driven by school counts, Zapata says.

51%

Percentage of the total 4,015 unhoused people counted in 2019, the most recent available count, who were considered “unsheltered”—i.e., living in a place “not meant for human habitation,” such as a vehicle, street or abandoned building: 2,037 in all.

37%

Percentage of the total 4,655 unhoused people counted in 2011 who were considered “unsheltered,” or 1,718 in all.

$16.2 million

American Rescue Plan funds budgeted for Commissioner Dan Ryan’s office to establish and run six “Safe Rest Villages,” including a “Safe Park Village” for vehicles, for up to three years, according to Ryan’s spokesman Bryan Aptekar.

$1.5 million

Estimated cost of bringing a considered Expo Center Safe Park Village up to permitting standards, according to Aptekar.

60

Maximum number of vehicles per city code that could be hosted on a theoretical, flat, paved 2-acre lot that Ryan’s office is considering, Aptekar says.

40

Average vehicles served by the Safe Parking Zone in Vancouver, Wash.