Multnomah County Auditor Jennifer McGuirk today released the results of her office’s audit of the county Public Health Division’s contact tracing, case investigation, and provision of services to people who contracted COVID-19.

The audit examined the period from the beginning of the pandemic through February 2022.

Early in the pandemic, Multnomah County, like public health agencies across the nation, aggressively pursued contract tracing as it historically has done with communicable diseases that afflict a far smaller percentage of the population.

Related: Reopening Oregon Depends on a Detective Squad Tracing Where Contagious People Have Been

But officials soon recognized they wouldn’t be able to keep up with COVID-19.

“The county’s COVID-19 contact tracing program did not contact all people who were infected with COVID-19 and their close contacts, especially when case numbers were high,” the audit found. “Contact tracing is less effective when a disease is widespread.”

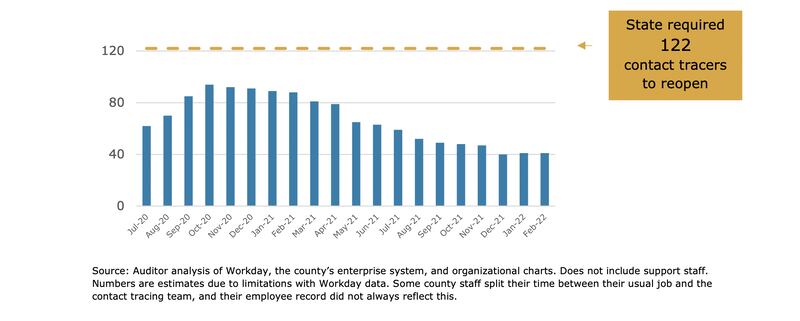

And COVID, of course, became very widespread. Although the county never reached the state-recommended staffing levels for contract tracers, the virus moved so rapidly and widely through the community that the shortfall probably didn’t make much difference.

“To be effective, contact tracing must be done quickly,” the audit found. “Because of the nature of the disease and the high number of cases, very few cases and contacts were traced quickly enough to disrupt transmission.”

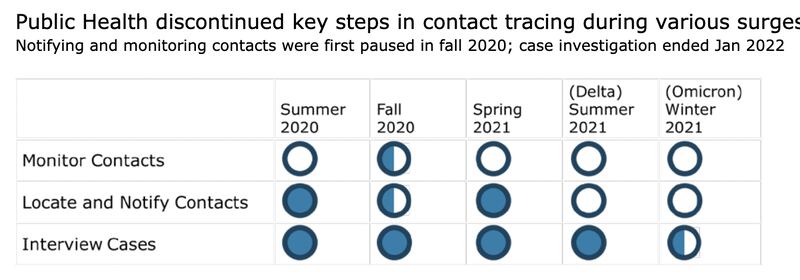

With each surge of the virus, the county contacted a smaller percentage of those who got COVID-19 and, following state and federal guidance, eventually phased out contact tracing.

Through January 2022, Multnomah County recorded 70,000 positive COVID-19 test results. Of that number, county case investigators interviewed about 30,000.

The audit noted that because the other 40,000 were not interviewed, they were less likely to receive the “wraparound” services the county provided.

The county had money to help those people unable to leave their homes or work: ”up to one month of grocery, utility, and rent/mortgage assistance” or, if necessary, help finding a place to isolate.

There were also technical issues, auditors found. For instance, county workers uploaded contact tracing data into a statewide database called ARIAS. But the auditors found that neither they nor county officials could access that information.

“Therefore, we only had access to data gathered from case investigation interviews of people with positive cases,” the auditors wrote. “We did not have access to data gathered from contact tracers notifying people of a close contact exposure. Without that data, we do not know how many people Public Health did or did not notify about an exposure.”

The county’s response suffered from other glitches as well. For instance, the county regularly told people with COVID-19 seeking services to call 211. But the 211 system would then instruct callers to contact the COVID Call Center.

“Calling 211 appeared to be an unnecessary step,” auditors wrote. “This extra step may have contributed to caller fatigue and unnecessary complexity during a time-sensitive and stressful period.”

The audit included seven recommendations for improvement, largely centered on ensuring that contracts with service providers include transparency and accountability measures; that the county prepare to deploy internal expertise more efficiently in future emergencies; and that top officials look backward at the pandemic for lessons learned so the county can be better prepared for future events.

Multnomah County Chair Deborah Kafoury said in a written response to the audit that she agreed with the recommendations.

“We recognize our accountability to the public and embrace a continuous quality improvement approach,” Kafoury wrote.