Four years ago, the last time Oregon elected a governor, Christine Drazan had never held elected office. She wasn’t influential, well known or feared.

Today, polling suggests she could be Oregon’s next governor.

A recent poll by DHM Research shows Drazan, the Republican nominee, with a 1-point lead over Democrat Tina Kotek—and far ahead of unaffiliated candidate Betsy Johnson. Most national election forecasters have handicapped Oregon’s gubernatorial race as a “toss-up.”

“There’s a pretty darn good chance that Drazan could win,” says Pacific University political science professor Jim Moore.

Drazan’s rise to this point is as fast as any in modern Oregon politics. Observers tell WW that’s because opponents have repeatedly underestimated her.

Behind a polite exterior, the 50-year-old former House minority leader from Canby maximized the power of a severely outnumbered Republican caucus by playing hardball that blindsided Salem veterans.

“She’s uniquely talented and incredibly ruthless,” says Greg Leo, a longtime lobbyist and former chairman of the Oregon Republican Party. “She rose quickly and broke some china in the process.”

Given that Oregon Democrats hold a 9.5-point voter registration advantage over Republicans and have won every governor’s race since 1986, it takes a bit of imagination to see Drazan’s path to victory.

But with Kotek trying to succeed the nation’s least popular governor and having to contend with the well-funded, charismatic Johnson’s efforts to peel away moderate Democrats, Drazan is in an unusually strong position for a Republican running statewide. And she’s running a campaign focused on problems that are easy to pin on Democrats—crime and homelessness, especially in Kotek’s hometown of Portland—while downplaying her unpopular positions on national issues (she scrubbed her anti-abortion stance from her campaign website).

Drazan’s greatest strength: She wasn’t in charge when she says Oregon hit the skids.

She can also argue that she stood up to the people who were.

WW interviewed more than three dozen sources for this story, including a dozen who asked for anonymity so they could speak honestly about Drazan without fear of repercussions. We found a politician on whom more experienced opponents have difficulty landing a punch—because her time in office has been so brief and produced few signature achievements.

It’s also because she’s used a strategy for success in a state where Republicans are outnumbered: The only way to win is not to play.

Those observers agreed that the key to understanding Drazan is the walkout she led in 2020 to oppose the passage of a bill to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

That walkout, while it had little practical effect, proved Drazan’s ability to galvanize her party and sparked a mutual antipathy between her and Kotek.

It also showcased what Drazan promises Oregonians now. If elected, she has proven she can effectively thwart Democrats’ agenda.

“They were going to run over anyone who stood in their way,” says state Rep. Shelly Boshart Davis (R-Albany), assistant leader of the House Republicans. “The person who stood in their way was a little redhead named Christine Drazan.”

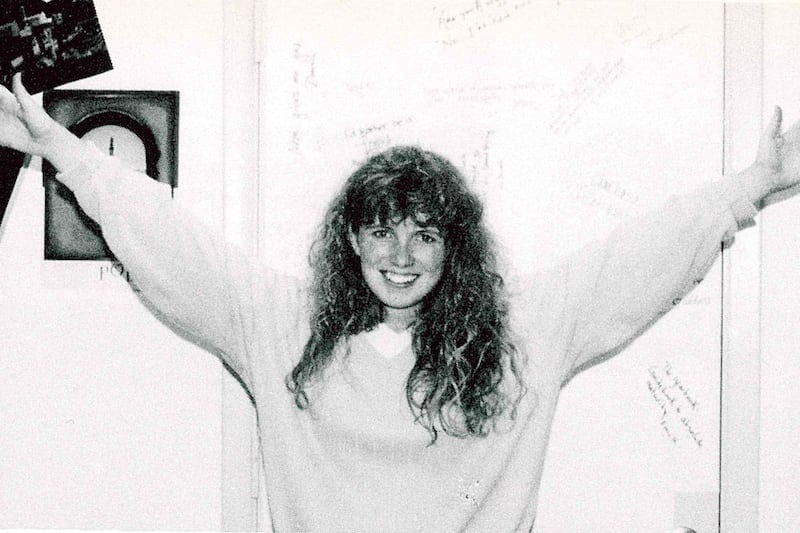

Drazan grew up poor, the daughter of a dad who worked in lumber mills and a mom who battled multiple sclerosis. “She’s got an interesting log cabin story,” Leo says. “She came up from the trailers in Klamath Falls.”

Drazan recalls having few pennies to rub together. “There wasn’t really a time that money wasn’t an issue while I was living at home,” she says. “We moved and moved and moved.”

She graduated from George Fox University in 1993 with a degree in communications before joining the Oregon Legislature as a staffer two years later. She rose to chief of staff for former House Speaker Mark Simmons (R-Elgin). “She always had her shit together,” Simmons recalls. “She did her homework.”

It was in his office that Drazan witnessed House Democrats walk out of the Capitol in June 2001, denying Republicans the quorum needed to pass a new congressional district map.

“Kate Brown walked out with ‘em,” Simmons recalls. “People don’t want to hear about that now. Democrats used to walk out when it benefited them. And now the unions want to make walking out a capital offense.”

Simmons saw no signs that Drazan would ever seek the state’s highest office. “She was intent on being a mother,” he says.

She stayed in the Capitol until 2003, then moved into lobbying, first as political coordinator for the Oregon Restaurant & Lodging Association, then as executive director of the Cultural Advocacy Coalition of Oregon, a nonprofit that seeks to expand access to arts and culture.

Nancy Golden was a board member for that coalition. She says Drazan was pivotal in helping CAC secure $6 million annually from lawmakers for arts organizations and museums. “I come from an education background,” Golden says, “and I thought that she would have been a great teacher.”

Arts funding is typically the turf of Portland liberals. But Drazan has a lifelong love of music and theater. “I just really love the tradition of going to see plays at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival,” she says. Her radio dial is programmed to 96.3 FM, a contemporary Christian station, and 98.7 FM, a country station nicknamed “The Bull.”

She and her husband, Dan, a lawyer in Portland, had three children. (They now range in age from a senior in college to a sophomore in high school.) And she watched as Republicans, who outnumbered Democrats in the Legislature for most of the 1990s, drifted into irrelevance.

“I can tell you,” Drazan said in an interview with WW, “the whole world is turned upside down with single-party control.”

Drazan ran for office in 2018, winning an easy victory for a House seat representing Canby. Within months, she challenged the caucus leadership of then-House Minority Leader Carl Wilson (R-Grants Pass).

Each party elects a leader for its side of the aisle. That person has control over how the caucus will prioritize elections and oversight of political strategies in the Legislature. It’s common for caucus elections to be hotly contested—but less so for a rookie lawmaker to usurp a leadership role.

One issue that fueled Drazan’s takeover: whether House Republicans should walk out of the Capitol and deny Democrats the minimum number of lawmakers that must be present to pass bills.

As a rookie lawmaker, Drazan rose to her feet in a caucus meeting in June 2019 and said her fellow GOP House members should not accept losing. Instead, they should join Senate Republicans and leave the Capitol.

Walkouts are effective because Oregon has a two-thirds quorum requirement, meaning even with a supermajority, Democrats still need some Republicans present in the legislative chamber to conduct any business.

Before the 2019 legislative session, many Republicans viewed quorum-denying walkouts as a nuclear option: useful as a deterrent in negotiations but ultimately damaging to everyone if deployed.

Republicans blasted bills they disliked in lengthy floor speeches. But when the speeches finally ended, the minority party could only cast futile “no” votes.

To traditionalists like Carl Wilson, the role of the minority party is principled dissent. (He did not return calls seeking comment for this story.) And the caucus rejected Drazan’s pitch. House Republicans stayed.

But Drazan’s unusual boldness made an impression on her colleagues. Three months later, House Republicans held a vote on who should lead the caucus. Drazan was elected that night, cutting Wilson’s expected two-year term as leader to a scant eight months. (The day after the vote, five House Republican office staff members submitted letters of resignation.)

“She was like a Michael Jordan in the caucus,” says state Rep. Daniel Bonham (R-Hood River), who entered the House shortly before Drazan. “That’s the person who needs the ball at the end of the game. She’s just that exceptional.”

Drazan’s ascent wasn’t achieved alone. She had the backing of Shaun Jillions—perhaps the most aggressive figure in Oregon business lobbying.

Jillions is a gregarious character: a burly back-slapper who likes University of Oregon athletics nearly as much as he dislikes taxes. Jillions, the longtime lobbyist for the Oregon Association of Realtors, which controls one of Salem’s largest PACs, spending about $1 million annually, also founded Oregon Manufacturers and Commerce in 2018, bringing together the state’s largest timber companies with smokestack industries. The combined might of his clients and his willingness to play hardball make him a force in Salem.

Two people familiar with the internal politics of the Oregon GOP tell WW it was Jillions who pitched Wilson on the idea of House Republicans walking out in 2019. Those sources say it was also Jillions who helped build support for Drazan’s candidacy to lead the caucus.

Jillions confirmed to WW that he had lost confidence in Wilson but denies walkouts were at issue and says his role in Drazan’s rise is overblown. “Members knew I had no faith in former Rep. Wilson’s ability to successfully run campaigns,” he says. “I view [the implication] as insulting that she wouldn’t be where she is if not for me. I have zero doubt, if Shaun Jillions wasn’t in Salem, she’d be in the exact same spot.”

As soon as Drazan took leadership, she demonstrated she was prepared to execute a new, confrontational approach.

During her first floor speech as Republican leader, she made her position clear. “I’m not here to advance someone else’s political agenda,” Drazan said on Feb. 6, 2020.

What that meant: She would not capitulate to Democrats. Republicans would be equals in Salem, even if that’s not what most Oregonians had voted for.

In high-leverage negotiations, she was rarely willing to give an inch.

“I always enjoyed talking with her,” says state Rep. Barbara Smith Warner (D-Portland), House majority leader under Kotek. “We had extremely pleasant conversations, but she never brought anything to the table.”

Heading into the 35-day legislative session in 2020, Democrats planned to ram through a rewritten cap-and-trade bill.

Republicans walked out. First, senators left. Then, House Republicans under Drazan’s leadership did what they would not do the year prior: They left too.

It worked: Although outnumbered 38 to 22 in the House, Republicans won. More than 250 bills died that session. Just three passed.

To the party in power, Drazan’s move was an affront to the rules of democracy.

“I just felt like she moved away from the democratic process and our rules, and every opportunity to obstruct became her agenda,” says state Rep. Paul Holvey (D-Eugene).

Smith Warner is more blunt: “Our caucus had no interest in negotiating with terrorists.”

Indeed, public employee unions are now asking voters to ban the practice of walkouts this November—placing Drazan and her defining tactic on the same ballot.

But to Republicans, long bereft of power in Salem, Drazan’s willingness to fight the Democratic steamroller was inspiring. “They wanted us to vote no and say thank you,” Boshart Davis says. “When Christine got in the way, that’s when you saw fireworks.”

The volatile relationship with Kotek exploded a year later, when the House speaker, exhausted by Drazan’s delay tactics, gave Republicans equal say in drawing new state legislative and congressional district maps—then reneged on the deal.

What finally propelled her into the race for governor, Drazan says, was the prospect of seeing Kotek win that position instead.

“I went through that redistricting process in particular with Tina Kotek, and her complete and total abject failure as a human being to keep her word and not lie is shocking to me,” Drazan says. “She cannot be governor of the state of Oregon.”

State Sen. Tim Knopp (R-Bend) sensed Drazan’s frustrations in dealing with Kotek. He and several colleagues were impressed enough with Drazan’s effectiveness at thwarting Democrats in 2021 to ask her if she’d like to move up to the Senate.

“She said, ‘I’d rather be governor,’” Knopp recalls.

Drazan’s brief legislative career consisted of blocking Democrats’ agenda.

“There was no legislative agenda coming from her other than to obstruct,” Holvey says.

As a candidate for governor, Drazan’s dubbed her plan the Roadmap for Oregon’s Future. It’s a generic list—safer streets, better schools, less red tape—perhaps because Drazan knows if she is elected, she’s mostly going to be playing defense.

Given Democrats’ voter registration advantage, Republicans have little chance of winning control of either chamber of the Legislature this year.

But there is plenty Drazan can do on her own.

She has promised to “tear up” Gov. Kate Brown’s executive order addressing climate change, fire Brown’s agency directors, and declare a homelessness state of emergency. (After the primary, Drazan scrubbed from her website mentions of her pro-life position, supporting the Second Amendment, and “securing” the state’s elections.)

Moreover, having a Republican in the governor’s office would provide the GOP with a veto over any legislation it finds objectionable, without the need for a walkout.

“As governor, she will use the veto pen so much, she’ll make Dr. No look like a lightweight,” says Leo, referring to the nickname former Gov. John Kitzhaber earned for vetoing Republican bills from 1995 to 2003.

As governor, Drazan says she would end the overreach she says defines Democratic control.

“I actually view government as having an essential role,” she says, “that should effectively advance core functions and not be all things to all people.”

Leo wonders if she can reach across the aisle. “The governor’s job is to persuade,” he says. “Can she have that kind of smoothness and charm? It remains to be seen. She’s kind of a partisan warrior.”

But others in her party think a Drazan governorship would achieve the bipartisan balance she’s always sought. “The Legislature will be forced to work with the governor and be accommodating,” says former state Sen. Kevin Mannix (R-Salem), who twice ran for governor. “I’m old school. I believe in that kind of dialogue.”

Such backers point to Drazan spurning the secessionist movement in Eastern Oregon. Only Drazan can draw those alienated rural counties back into Oregon’s social compact, they say.

“I’d be over the moon if we got a set of checks and balances in there,” says state Sen. Lynn Findley (R-Vale). “We walked a lot, but we walked because we were completely ignored. Why is my voice irrelevant?”

For the next six weeks, Drazan will cast voters’ decision as the same binary choice she’s seen the world with for years: me or a state ruled by Tina Kotek.

Her walkout worked, she says, and with her in the governor’s office, Republicans can finally bring checks and balances back to Salem.

“I have been up against Tina Kotek when the deck has been stacked and when the math was tough,” Drazan says. “This is the year for Republicans to win. This is an opportunity to actually make a difference.”

Showing Teeth

During her time as a lawmaker, Christine Drazan earned a reputation for sky-high expectations and treating the people she worked with harshly when those expectations were not met.

One case involved an employee of the Oregon Health Authority, according to documents obtained by WW via a public records request.

The dispute occurred in August 2019, when Drazan was connected by telephone with a coordinator of dependent eligibility review for the Public Employees Benefit Board at OHA, according to a series of emails and handwritten notes taken during a later conversation between the coordinator and the Oregon Legislature’s human resources director.

According to the OHA employee, Drazan was “incredibly angry” during the call, “yelling” and attempting to use her position to intimidate the employee to obtain special treatment.

At issue: One of Drazan’s children did not have dental insurance for an appointment. According to the employee’s complaint, Drazan’s insurance for her child was suspended after Drazan did not respond to emails asking her to provide documents confirming continued eligibility. State employees and their dependents are occasionally subject to eligibility review by PEBB.

When the employee told Drazan she needed to provide the documents before the insurance could be restored, Drazan asked the employee if she knew who Drazan was and demanded to be put back on insurance right away, the employee alleged.

After the employee told Drazan that was not possible, the employee alleges Drazan called Patrick Allen, director of the Oregon Health Authority. Allen, with other top OHA officials, decided to put Drazan back on the insurance immediately and allow her 60 days to submit the needed documentation, the employee alleged.

The employee—whose name was redacted from the documents WW obtained—said in her complaint she had never experienced anyone trying to use their position to get around the rules, despite having worked with other powerful public employees, such as judges, district attorneys and state senators.

As a remedy, the employee asked Drazan to apologize. The day after the complaint was filed, Drazan dropped off to human resources a handwritten note on lined notebook paper that read:

“Dear [redacted], I sincerely apologize for my interaction with you earlier this week. I should have been more patient—and polite. Please accept my sincere apology. Sincerely, Christine Drazan.”

In a follow-up email with the HR director, the employee acknowledged Drazan’s apology was what she had asked for and hoped that “in the future she does not use her position to try and intimidate to get her way.”

Allen, via a spokesman, refused to respond to the allegation that he and other OHA officials improperly used their positions to benefit an elected official. The health authority would not provide any additional details on the case due to privacy laws.

The Drazan campaign denies she improperly used her position to circumvent PEBB rules.

“We wholly reject the premise that Christine abused her power in any way or received any special treatment from the Oregon Health Authority,” campaign spokesman John Burke said in a statement. “As any parent would, she was making sure her family and her children had access to care they were entitled to.”

Drazan is also said to have directed her anger at legislative aides.

Several individuals say she had a habit of “bullying” and “demeaning” staff, both in private and in front of other lawmakers.

One source with firsthand knowledge says Drazan was the subject of three informal complaints to the Legislative Equity Office by the end of 2020 due to treatment of staff.

Drazan calls those claims “baseless.”