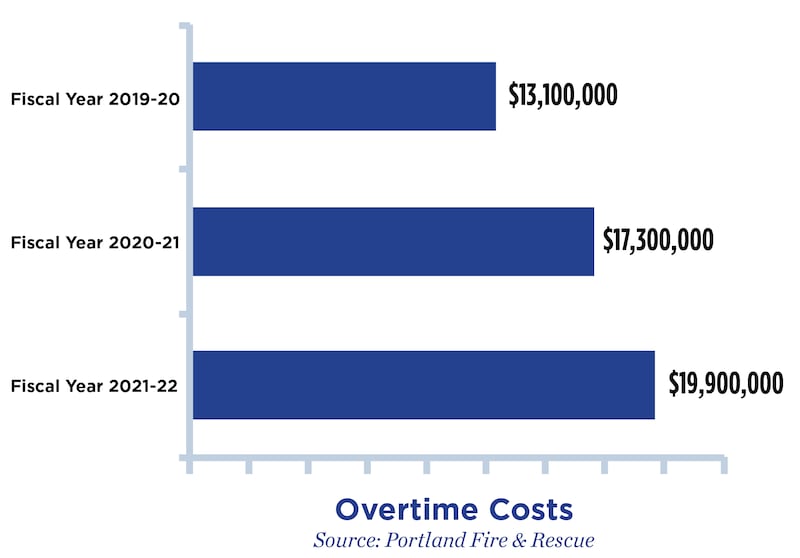

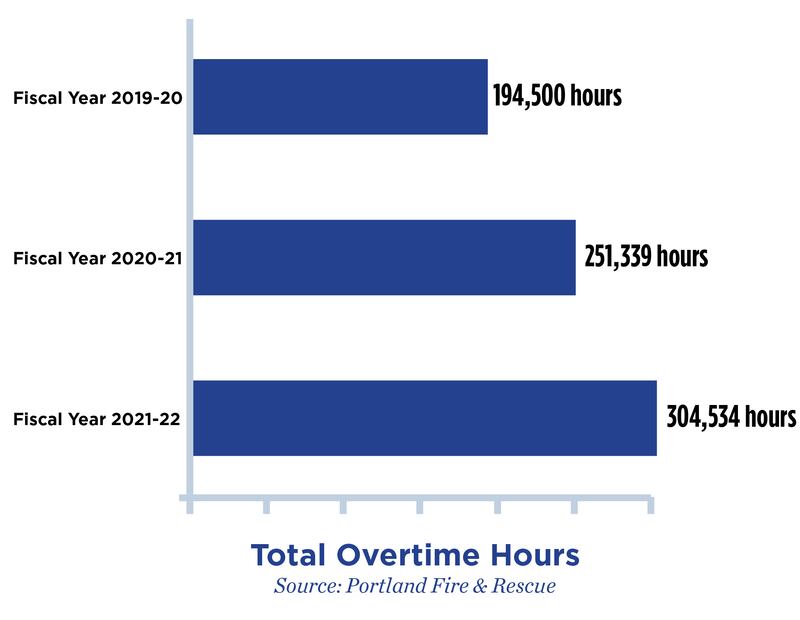

Portland Fire & Rescue spent nearly $20 million on overtime pay this past fiscal year. That’s a 54% increase from two years prior—a spike that onlookers say signals something is very wrong within the fire bureau.

But for the Portland Firefighters Association, which represents all 644 sworn Portland firefighters, the rising price tag isn’t the most troubling part of the story.

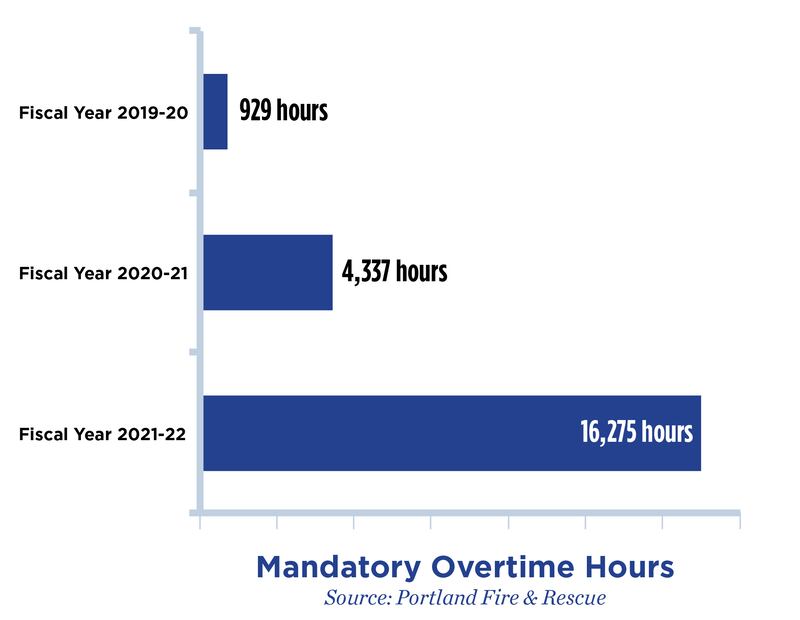

What most concerns the union is that firefighters over the past fiscal year worked more than 16,000 hours of mandatory overtime—extra hours they were forced to clock. That’s 275% more hours than they were forced to work the year before, and firefighters are penalized if they don’t show up for mandatory overtime shifts.

Union president Isaac McLennan says the ranks are exhausted and demoralized.

“We’re at a breaking point,” McLennan says. “I’d literally never seen a mandatory shift until protests and COVID-19. When we heard they were mandatory, we were just floored. We saw this coming and we warned [the city].”

On the heels of a consultant’s recent report on behalf of the fire bureau—which showed chronic understaffing, stations left unstaffed in the most vulnerable parts of East Portland, and less than optimal response times—the cost of overtime is another warning sign of something amiss.

Portland Fire & Rescue spokeswoman Kezia Wanner says the bureau “is assessing the sufficiency of the current number of authorized firefighters” and adds that a primary driver of the spike in mandatory overtime hours was COVID leave.

The bureau would not comment on whether it’s striking the correct balance between paying overtime and hiring new firefighters—though for the first time in the bureau’s history, Fire Chief Sara Boone made 13 lateral hires this spring to staff up.

The union argues that the figures speak for themselves—and factor into its decision not to endorse the reelection of City Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty, who oversees the fire bureau.

“That number itself is shocking,” McLennan says. “It’s not our fault that we’re short so many people. You’re forcing us back to work for fear of discipline. Morale in the fire bureau is the lowest I’ve ever experienced in my career.”

A number of factors created the staffing shortage and spike in overtime hours at the fire bureau.

Twice in the past decade, the bureau paused its training academy. The academy currently graduates an average of 24 firefighters a year. The last time it paused was under Fire Chief Mike Myers in 2019.

“When they did that, we were flush with people. It seemed like the fiscally smart thing to do,” McLennan says, “but it takes two years to make a firefighter.”

A pause on the academy for three years beginning in 2011 also shorted the bureau dozens of new firefighters. Meanwhile, older firefighters continued to retire as the workload for existing firefighters climbed.

Another contributing factor was the labor contract the union and city negotiated in 2019. The union scored several substantial wins: a shorter workweek and more vacation leave.

To make up for increased vacation leave and the shorter work week, the city agreed to add $5 million in funding for 34,200 additional overtime hours. It was then-union president Alan Ferschweiler’s understanding, per documents he saw during negotiations with the city, that 14 full-time firefighter positions would be added in the next budget. (Documents obtained by WW are ambiguous on that count.)

But no such funding for additional firefighters was included. (Wanner says the bureau is, however, “taking measures to bring down overtime costs” by requesting funding in the fall budgeting cycle for 13 additional firefighters.)

Randy Leonard, a fire union president in the 1980s and ‘90s and later a city commissioner who oversaw the fire bureau, says the $20 million overtime price tag is a signal that the bureau hasn’t hired consistently.

“I would conclude they just don’t have enough firefighters working. They need to hire more firefighters,” Leonard says.

The bureau’s number of firefighters has remained mostly stagnant for 20 years, while Portland’s population has steadily grown, as has the number of calls for service.

In 2011, firefighters responded to just over 67,000 calls. In 2021, that number ballooned to 86,000.

Union leaders say the effects of hiring decisions over the past decade are finally coming to bear on firefighters working today.

Last Thursday, for instance, 29 firefighters worked overtime shifts out of 169 on duty daily, according to McLennan. That means 17% of the firefighters that worked Sept. 29 made 1.5 times their normal pay.

Firefighters’ exasperation boiled over this summer, when the Portland Firefighters Association asked Commissioner Hardesty for double pay for overtime hours worked this summer. Chief Boone supported the request, but later advised Hardesty in a Sept. 8 email reviewed by WW not to grant the request now that mandatory overtime would likely fall throughout the winter.

“Our understanding is that the financial analysis is what led to Chief Boone not supporting the proposal at this time, despite previously advocating for this proposal,” says Hardesty spokesman Matt McNally.

(The union argues Boone’s reversal was because the critical time had passed. The chief’s office did not respond to a request for comment.)

Update: After print deadline, chief spokesperson Aaron Johnson said in an email that Chief Boone “has always supported paying members double time for mandatory overtime during peak vacation season, which also coincides with wildfire season. However, she cannot support an incentive proposal by using $1.6 million from the bureau’s existing budget.”

Hardesty didn’t grant the request, though emails reviewed by WW show her office did consider the idea and consult with other chiefs of staff. “I think it’s bad public policy to pick out a small group of public employees and pay them double time,” Hardesty says—and she criticized Commissioner Mingus Mapps for granting double time for 911 dispatchers who echoed similar dissatisfaction.

McLennan says Hardesty’s refusal to bring a double-time proposal to the Portland City Council was “the straw that broke the camel’s back” and one of the reasons the union endorsed Rene Gonzalez for City Council—Hardesty’s opponent whose platform focuses on supporting police and enforcing anti-camping laws.

“Our fire commissioner should be a champion of the fire department,” McLennan says. “I’m not seeing a champion for the fire department. She says she is, but just saying it does not make it so.”

Hardesty contests that characterization.

In a recent endorsement interview, Hardesty said that “no commissioner has done more for the fire bureau” than she has. She pointed to the $5 million in overtime added to the fire budget to allow for increased vacation leave and a recent $2.1 million federal grant to reopen a station in East Portland and hire six additional firefighters.

She added that she “inherited decades of neglect” at the bureau and has fought against budget cuts, restricted tent camping in wildfire hazard zones, banned fireworks, and added mental health resources for firefighters.

“I would challenge anyone to find someone who has done more to modernize Portland Fire & Rescue during a three-year period than I have as fire commissioner,” Hardesty says.

Ferschweiler, the union president before McLennan, agrees Hardesty battled to keep fire staffing levels stable, fought back decreases in the fire budget, and negotiated the latest contract favorable to firefighters.

“She fought to make sure we didn’t have any budget reductions for our fire stations over the past two budget cycles,” Ferschweiler says. “And she fought to keep our stations open.”

Union members soured, however, at offhand comments Hardesty made, he says. “When all the protesting was going on downtown, it was a bad time for her, but she said, ‘The protesters put out the fire. The fire bureau couldn’t even put it out.’ Our members just about lost their shit.” (Her exact quote: “Neither police or fire and rescue could have put those fires out.”)

And while the number of calls over the past five years has remained steady, the duties of the fire bureau have changed substantially because of the deepening homelessness crisis: Nearly 1 in 2 fires the bureau responded to in 2021 occurred at homeless camps.

Ferschweiler and McLennan agree the increase in homelessness has made their jobs harder.

“There’s no working smoke detectors in these tents,” Ferschweiler says. “The very thing we worked hard to do, [policies around homelessness] are reversing that.”

Leonard, the fire union president throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s, says the mandatory overtime hours show firefighters are reaching a breaking point.

“My reaction isn’t that I’m alarmed at the overtime, but the impact on the existing firefighters has to be compelling,” Leonard says. “It’s got to be a burden to go to work in the morning and for someone to call you and say, ‘You’re not going home today.’ That sounds depressing to me.”