As the Nov. 8 general election approaches, crime and the condition of people living on Oregon’s streets are hot-button issues.

Part of the discussion: Measure 110, the ballot initiative voters approved in 2020 by 58% to 42%. The measure decriminalized possession for personal consumption of many drugs, including methamphetamine and heroin, and diverted most of the state’s recreational cannabis tax revenue to new referral and treatment services for substance abusers. Decriminalization began in February 2021; treatment funds are only now beginning to flow.

RTI International, an independent, nonpartisan research firm based in North Carolina’s Research Triangle, got an interesting assignment earlier this year: Figure out how well Measure 110 is working.

Arnold Ventures, a philanthropy funded by billionaire John Arnold, gave RTI a four-year grant to evaluate M110. Arnold shifted from managing money to focusing on public policy in 2012 (he spent $2.75 million in 2014 on an unsuccessful measure to open Oregon’s primaries). RTI, founded in 1958, employs 6,000 experts in policy analysis. It formed a team of criminologists, sociologists, epidemiologists and economists to evaluate Oregon’s first-in-the-nation experiment.

Earlier this year, RTI staff traveled to Oregon to interview 34 people in law enforcement and social services about Measure 110—and, when the team began crunching numbers on its first data set, calls for police service. (Like FBI crime stats and Multnomah County’s biannual homeless count, calls for service are an imperfect indicator, but they provide a basis for comparison with other cities and over time.)

Hope Smiley-McDonald, a sociologist and director of RTI’s Investigative Sciences program, led the first of a series of looks at Measure 110.

In an interview that’s been condensed and edited for clarity, she told WW what her team found.

WW: How did you evaluate Measure 110?

Hope Smiley-McDonald: To start, we concentrated on law enforcement since the decriminalization aspect of Measure 110 was implemented first. We looked at two components of the law enforcement piece: how Measure 110 was rolling out in particular communities and how it was impacting the law enforcement agencies that were told to carry it out.

We visited four counties, two large and two small, separated geographically. We spoke to 20 people in law enforcement, including police, district attorney’s offices, community corrections and juvenile justice. And then the other 14 individuals represented social service and health agencies, including treatment and harm reduction agencies.

What did you hear in those interviews?

Law enforcement representatives gave us the impression that Measure 110 had resulted in increased crimes, especially as it related to property crimes and disorder.

They would often tell us, “Measure 110 has resulted in more crimes. We’re seeing a lot more property crimes than we have before. A lot more disorderly conduct.” They really were clear that there was a before and after.

What data did you look at?

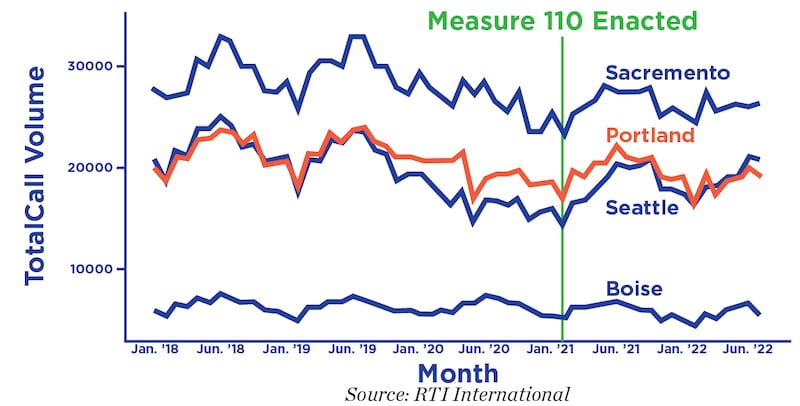

Calls for service. Those data reflect what the public is asking law enforcement to handle. And it also provides a window into how officers are spending their time. We compared Portland to peer cities over time to see what was going on in Oregon before and after.

What surprised you about what you found?

Bottom line: We’re really not seeing any change in Portland’s calls for service initiated by the public after Measure 110 was enacted. It’s pretty surprising to see that Portland mirrors its sister cities because there is a perception that, after Measure 110, crimes have increased and the public is no longer as supportive as in 2020.

Is it possible Portlanders simply stopped calling the police?

If that’s the case, then you would expect the calls for service to go down right after 110. That’s not the case.

What else will RTI look at?

We are certainly going to be looking at overdose fatality data, but those data have a bit of a lag time. The main drivers of change with overdose in terms of substance use treatment and harm reduction services are not really in place just yet. We’re probably not really looking to see what that change looks like, at least for another year.

What would you say to citizens upset by Measure 110?

I would urge patience. Any benefits from Measure 110 won’t appear in the health outcomes data for some time because the treatment and harm reduction services were only just funded in the past three months.