On a chilly morning last February, in the parking lot of a Beaverton Home Depot, a catalytic converter was harvested from a Ford pickup, one of hundreds stolen each month in Oregon. At black-market prices, the torpedo-shaped hunk of metal was worth upwards of $1,000.

Catalytic converter theft is a national headache, tripling year over year in 2020 and again in 2021, fueled by the skyrocketing price of the precious metals they contain. Portland has been no exception.

Few nonviolent crimes contribute so greatly to Portlanders’ unease about the safety of their city, but no one could say exactly where the stolen goods were going.

Until now.

WW has learned that the theft of catalytic converters outside a Beaverton strip mall has connections to a Long Island fence supplying a major New Jersey metal recycler.

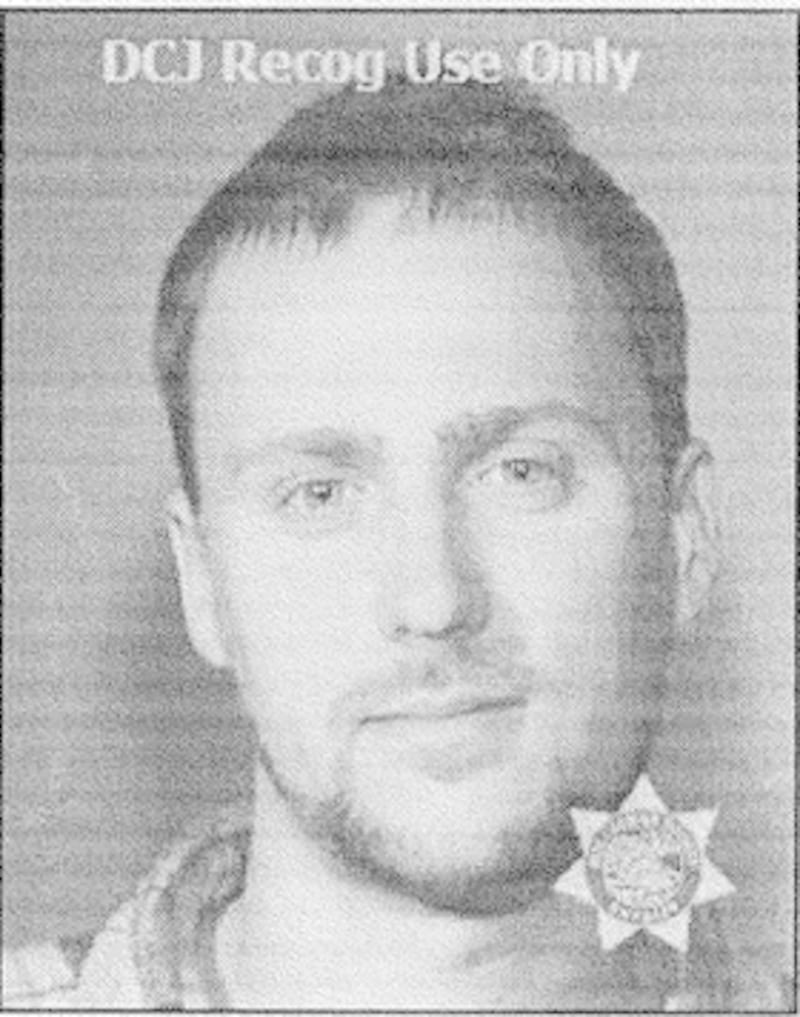

Specifically, a series of indictments alleges that catalytic converter theft is connected to organized crime and that an unassuming former Uber driver named Brennan Doyle, living in Lake Oswego, is the ringleader of an Oregon effort that reaches all the way to industrial parks and refineries on the East Coast, part of what federal and local prosecutors say was a half-billion-dollar nationwide criminal conspiracy.

On Aug. 2, Doyle was arrested and charged with racketeering and with turning 44,000 allegedly stolen catalytic converters into millions of dollars in cash. Doyle, 32, is alleged to have roped in high school buddies, girlfriends and small-time crooks to help him traffic a significant portion of the auto parts sawed from the undercarriages of Portland cars.

He has pleaded not guilty.

“[Doyle] is probably more responsible than anyone for the scourge of catalytic converter thefts in the state of Oregon,” says Washington County chief deputy district attorney Bracken McKey. “He is somebody facing a tremendous amount of prison time. We intend to get it.”

The month after Beaverton police raided Doyle’s Lake Oswego rental home, catalytic converter theft in Portland dropped 28%, according to Portland police. (The bureau has yet to release more recent data.) The Washington County Sheriff’s Office saw a more significant drop: from over 20 thefts a month in early 2022 to five in October.

Large as the bust was, no one thinks Doyle’s crew was handling all or even most of Portland’s stolen catalytic converters. Much of the evidence used to indict Doyle and his accomplices remains under seal.

But a review of court documents, along with dozens of interviews with detectives, cronies, friends and victims, provides clues to what became of many of the auto parts that disappeared from Portland cars over the past two years.

It takes less than a minute to extract a catalytic converter from the exhaust pipe of a Honda.

“They can be in and out in 30 seconds,” Beaverton Police Officer Matt Henderson told reporters earlier this year. “Like a NASCAR pit crew.”

Catalytic converters became widespread thanks to the federal Clean Air Act of 1970, which set strict limits on car emissions. The devices convert poisonous carbon monoxide in car exhaust into carbon dioxide.

To quicken that chemical reaction, the converters use three metals: palladium, platinum and rhodium. It’s incredibly effective, says Robert Farrauto, a Columbia University professor and pioneer in the field. When mixed with the right amount of oxygen, the catalysts eliminate upward of 95% of the poisonous fumes.

But because the exhaust is so hot, the device must be placed underneath the car. “It’s effectively a black box in a pipe,” Farrauto says. It’s an easy target for thieves. “You cut each end, take the converter out, and there it is.”

The price of these “platinum group metals” has surged in recent years. In 2018, the National Insurance Crime Bureau recorded 1,298 catalytic converter theft claims in the United States. By 2021, there were over 52,000 claims.

Kevin Demer, senior deputy district attorney at the Multnomah County District Attorney’s Office, has prosecuted catalytic converter thieves for decades. He’s seen theft spikes before. But this one has been extreme. With so much demand, new buyers willing to purchase catalytic converters with an uncertain pedigree popped up like weeds.

Established players in the metal recycling market avoid buying stolen car parts by verifying the identities their sellers. But the new ones didn’t.

“The companies that are dirty don’t have those controls,” Demer says. “They’re ostriches in the sand.”

Into this frothy market stepped Brennan Doyle.

Oswego Lake has long been a magnet for Portland’s wealth. When two 30-somethings rolled into a lakeside rental earlier this year in an expensive new truck, no one batted an eye.

According to Beaverton detectives, Doyle and his high school buddy, Benjamin Jamison, set up shop in a $5,000-a-month two-bedroom home on South Shore Boulevard for the summer.

Prior to landing in Lake Oswego, Doyle was born in San Francisco and later graduated from Tualatin High School. He drove for Uber, according to two longtime friends who spoke to WW on condition of anonymity. In 2015, he registered a sporting goods business with the state. It sold snowboards and hats, but never appeared to gain much traction. Jamison had known Doyle since high school and worked in construction before Doyle pitched him on the new enterprise, Detective Patrick McNair of the Beaverton Police Department tells WW.

Doyle bought a speedboat for $15,000 and spent evenings cruising the lake. He and Jamison invited friends from out of town, who documented the outings on Instagram. In one, Doyle mugs for the camera in a teal swimsuit, then leaps off the boat’s bow and swims off into the distance.

Next-door neighbors tell WW the two friends seemed like nice kids. They held parties, with cars spilling out onto the streets, but told neighbors to give them a call if their guests ever got too loud.

Doyle was a fan of the Golden State Warriors, and in July flew to San Francisco to watch the team play in the NBA Finals. He and his friends documented trips to the Coachella and Stagecoach music festivals on Instagram. Doyle had plans to go to Bali, police say.

According to police, Doyle didn’t use the lake house just for pleasure. He and Jamison were visited regularly by men instructed to carefully conceal their deliveries in bags or under blankets.

“This place was the heart of the business,” McNair tells WW.

According to a July indictment, Doyle’s criminal enterprise began in early 2021. Doyle and a few friends allegedly purchased catalytic converters from thieves up and down the West Coast. But according to McNair, one of Doyle’s major suppliers was Tanner Hellbusch, the man spotted on the security video from the Beaverton Home Depot during the February theft from the Ford pickup.

Hellbusch, 32, was scraping together a living by reselling cars and their parts. He’d been convicted of DUII three times and, by 2015, he’d lost his driver’s license. As of September, he owed his ex-wife over $17,000 in child support.

By February, he had begun stealing catalytic converters, according to an indictment. He was a major local fence, McNair says, either stealing converters himself or buying the parts directly from thieves and reselling them at a profit.

He lived with his new fiancée, Jerrica Oga-Garo, and their newborn in a three-bedroom rental on a quiet cul-de-sac in Beaverton’s Oak Hills neighborhood. “He seemed like a really friendly guy,” says Peter Stamos, who lives two doors down.

Meanwhile, according to McNair, Hellbusch was posting advertisements seeking sellers for catalytic converters on Facebook Marketplace—and uploading photos of his hauls.

Hellbusch was doing business out of Oga-Garo’s parents’ home, police say, across the railroad tracks from Nike’s World Headquarters. There, Hellbusch met with buyers and stored the stolen merchandise. When making deliveries, Oga-Garo sometimes drove, police say. Like Hellbusch, she’s been charged with theft and racketeering.

At first, Hellbusch was reselling the catalytic converters to local scrap businesses, McNair says. But an Oregon law passed in 2021 required scrap metal businesses to begin keeping records of every catalytic converter they buy, including the vehicle identification number of the car it came from—and made it illegal to purchase the parts with cash.

The state’s metal recycling industry had reservations. “Unscrupulous buyers,” lobbyist Justin Short told legislators, would just “seek out locations with less restrictive laws to do business.”

Short’s prediction proved prescient. Thieves started looking for new buyers.

That’s when police say Brennan Doyle stepped in.

“It was about when that happened that Hellbusch started [selling his contraband] through Doyle,” McNair says.

Doyle found an out-of-state buyer in Adam Sharkey, detectives say. Sharkey was a major East Coast fence who was buying catalytic converters in bulk from across the country and shipping them to Long Island, N.Y., according to a federal indictment.

Sharkey couldn’t have been hard for Doyle to find. “Looking to buy volume,” Sharkey wrote in December in a Facebook group for buyers and sellers of catalytic converters. “Will pay shipping 100+ pieces,” he added. Sharkey included his phone number.

Leveraging his new hookup, Doyle set up a warehouse on a property in Aurora and recruited friends to help launch the business. Jenna Wilson, his on-and-off-again girlfriend, kept the books, detectives say. Benjamin Jamison, his Lake Owego roommate, met with buyers and handled the cash. Both have also been charged with theft and racketeering.

As spring turned to summer, detectives watched as a steady stream of trucks pulled in and out of the Aurora warehouse.

Meanwhile, federal investigators were tracking Adam Sharkey.

In an investigation codenamed Operation Heavy Metal, Oklahoma detectives traced stolen catalytic converters from a fence in a Tulsa suburb to Sharkey’s warehouse in Long Island. Investigators confirmed to WW that Doyle’s catalytic converters made the same journey, by commercial truck and rail, as the Oklahoma car parts.

The Oregon investigation didn’t pursue the stolen goods any further than Sharkey. Saying what happened to them next requires a little conjecture. But that second investigation based in Oklahoma outlines in documents what became of catalytic converters Sharkey fenced—and identifies a likely final destination.

Adam Sharkey was selling stolen catalytic converters to a New Jersey company called DG Auto, according to an indictment unsealed in early November. By the time the feds pulled down the Oklahoma ring, DG Auto had wired Sharkey more than $45 million.

DG Auto, based in suburban Freehold, N.J., 30 minutes outside Trenton, was not your run-of-the-mill metal recycler. It had a mobile app, which provided real-time quotes on the value of catalytic converters as the underlying metals fluctuated in price.

“With over 12,000 codes and over 10,000 photos of converters, you will have the most accurate information on converters at your fingertips,” reads the recycler’s website.

DG Auto would “decan” the catalytic converters and extract the precious metals from inside. The process is decidedly low tech. A miniature guillotine rips open the device’s metal can to expose the fragile core, which is then crushed into a powder. The company posted pictures of its shiny new decanning machine online.

Federal prosecutors say DG Auto sold the powder for a profit to “a metal refinery company operating in New Jersey and elsewhere,” which was not named in the indictment. Portland prosecutors say metals from Doyle’s shipments eventually ended up “overseas.”

Regardless, after the powder is subjected to intense heat and the precious metals extracted, the metals likely wind up back where they started: in a catalytic converter. The devices use around half of the world’s supply of palladium and 80% of its rhodium.

The nationwide “recycling” of these metals proved lucrative for DG Auto’s owner, Navin “Lovin” Khanna, 39.

The U.S. Department of Justice says that between 2019 and the summer of 2022, the unnamed refinery paid Khanna and his brother, Tinu “Gagan” Khanna, more than a half-billion dollars.

“They made hundreds of millions of dollars,” FBI Director Christopher Wray later said. “On the backs of thousands of innocent car owners.”

Over the summer in Oregon, two dozen police officers, sheriff’s deputies and state special agents watched Doyle’s lake house and warehouse in shifts. The Beaverton Police Department led the investigation, which had started with tips from one of their patrol officers and a Clackamas County detective that Hellbusch was a major buyer of stolen catalytic converters.

But when police observed delivery trucks backed up to the warehouse, the cargo was hidden from view. And detectives found it difficult to prove that Doyle was aware he was trafficking in stolen goods.

So the Oregon Department of Justice helped police tap four phones, including Doyle’s.

“The wiretaps were the difference maker,” McNair says. Using phone records and freight receipts, detectives were able to piece together the organization—and ultimately connect Doyle to Sharkey.

Doyle did little to hide his trail. He and his friends discussed shipments over the phone, including who was making deliveries and the amount of cargo, says Phillip Kearney, assistant special agent in charge at the Oregon DOJ. “They were flamboyant—kind of party boys,” Kearney says.

Over the summer, Kearney says, police began seizing assets and intercepting the ring’s wire transfers. On July 18, one of Doyle’s childhood friends and alleged accomplices, Casey Smith, went online to complain that he’d been locked out of his Chase bank account—and access to $130,000. Smith faces similar racketeering charges.

Later, the friends met to discuss their financial woes over lunch at nearby sandwich shop Lardo. Unsure whether their money had been frozen by the feds or they’d simply been victims of bad luck, the crew brainstormed possible workarounds.

Kearney tailed them and sat in an adjacent booth, listening in.

On Aug. 3, a SWAT team descended on Hellbusch’s house. Police raided Doyle’s lakehouse and searched the pair’s warehouses. They found nearly $40,000 in cash in Doyle’s bedroom. In the warehouses were 3,000 catalytic converters.

Authorities collected more than 1,100 pages of financial records and recorded nearly 3,000 audio clips. A grand jury indicted 14 people, nearly all charged with racketeering and various counts of theft and money laundering.

In total, Beaverton police say, Doyle and his cronies sold worth $22 million worth of catalytic converters in the past two years.

At least $10 million of that money flowed through Doyle’s bank accounts, prosecutors say. “We haven’t tracked down all of his cash,” chief deputy DA McKey told a judge at a court hearing in September.

“I’ve been doing this for 17 years. I can’t think of another property crimes wire case this big,” says Detective Sgt. Cliff Lascink with the Washington County Sheriff’s Office.

When WW called Doyle to request comment for this story, he declined and hung up.

More: Once a target of catalytic converter thieves, an auto repair shop takes matters into its own hands.

Doyle gave up the lease on his lake house. The owner put it back up for rent in October. Hellbusch’s house on the Beaverton cul-de-sac is vacant.

It’s not clear how much money the two had left after blowing much of it on jewelry, trips and fancy cars. Detectives say Doyle owed more on his new Bronco than it was worth. According to his attorney, Doyle now spends his days washing cars at an auto dealer in Vancouver.

If the case goes to trial, Doyle will likely claim he didn’t know his business was trafficking in stolen goods. His friends say he’s being scapegoated for Portland’s crime problems.

The all-hours surveillance means prosecutors have hours of recorded phone calls and troves of financial documents to make a case that Doyle knew the illicit origin of his product.

But tracing any given catalytic converter from the underside of a Portland car all the way to a New Jersey metal refinery is next to impossible. The trail WW traced for this story disappears in places. Unlike other car parts, catalytic converters have no unique identification number that can be used to trace them back to their original owners.

Federal legislation introduced earlier this month by U.S. Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) would change that, requiring that new vehicles’ catalytic converters be stamped with the VIN.

It’s “one step closer in the fight to end catalytic converter theft,” Wyden says.

Although catalytic converter theft dropped significantly in Portland in August, the problem is still far from being solved. Doyle’s organization wasn’t unique even in Oregon, DOJ agent Kearney says. “It is probably one of a few of that size.”

The Converter Connection

Thanks to a pair of recent criminal investigations, it’s now possible to trace the path catalytic converters took from the streets of Portland to an indicted New Jersey recycler.

1. Pro Automotive & Diesel

Scappoose

Targeted by catalytic converter thieves on multiple occasions, including by a known associate of Tanner Hellbusch.

2. Taylor Hellbusch’s Storehouse

Beaverton

Police say Hellbusch fenced stolen catalytic converters through this suburban house near the Nike campus.

3. The Lake House

Lake Oswego

Hellbusch and others brought merchandise to Doyle here, police say.

4. Brennan Doyle’s Warehouse

Aurora

Doyle’s associates boxed up catalytic converters here before loading them onto trucks and shipping them out of state, detectives allege.

5. Adam Sharkey

Lindenhurst, NY

Police say Sharkey received shipments from Doyle here.

6. DG Auto

Freehold, NJ

An Oklahoma indictment shows Sharkey received $45 million for catalytic converters shipped to a company operating out of this New Jersey warehouse.