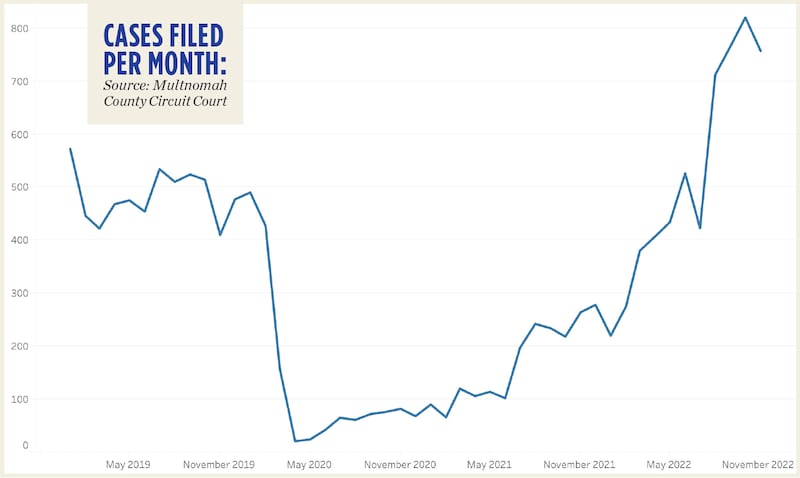

As pandemic-related tenant protections fall away, Portland evictions have skyrocketed. Since August, the number in Multnomah County has easily eclipsed pre-pandemic totals, rising above 700 per month.

In April 2020, evictions plummeted after the state issued a near blanket ban. This October, Oregon’s “safe harbor” law stopping the eviction of tenants who have applied for rent assistance ended. It had become less useful anyway— the state’s rental assistance program ran out of funding in August.

At a recent legislative hearing, Cameron Harrington, director of policy at the housing advocacy organization Neighborhood Partnerships, characterized the recent spike as a “dramatic cliff that renters are falling off.”

In 2019, Multnomah County Circuit Court recorded about 500 eviction cases each month. By this October, that number was 820. A vast majority, 92% in October, were for nonpayment of rent, according to an analysis of county court records by the Eviction Defense and Diversion Evaluation team at Portland State University.

This demonstrates a “direct relationship” between the loss of tenant protections and people being forced out of their homes, says Becky Straus, the managing attorney at the Oregon Law Center who provides legal assistance to people facing eviction.

One of the biggest eviction filers was Stark Firs Management, a company that manages 75 buildings in east county. It has 2,000 units. So far this year, it has filed 235 eviction cases, according to WW’s analysis of eviction records.

Moe Farhoud, its owner, says nearly a quarter of his tenants were behind on rent—up from only 2 % to 3% prior to the pandemic. “These people thought they could live for free,” he says. “At the end of the day, it’s very sad.”

Not everyone who ends up in court loses their home. Some negotiate payment plans. Still, court records likely underestimate the total number of people displaced due to their inability to pay. Landlords are required to give tenants a “termination of tenancy” warning, which no one tracks. Often, tenants simply pack up and leave before legal paperwork is filed.

If they do decide to fight, they’ll end up in the Crane Room on the second floor of the Multnomah County Courthouse.

On a recent Friday morning, Judge Pro Tem Monica Herranz worked down her list of cases, encouraging tenants and landlords to make deals. If they don’t, the case goes to trial.

That rarely happens. There’s a “high likelihood you will lose,” Herranz admonished one man, and warned him he’d have to pay his landlord’s attorney fees if he did.

Like many of the people in that courtroom, 37-year-old Audrey Hannon made a deal. She had a small clothing design business, but it was struggling. Her $745 monthly rent had been paid off by rent assistance programs for years, court records show. Now, her landlord says, she owes more than $3,000.

She told the judge she would pay it back by the following Monday.

Hannon didn’t have it—she planned to ask the county for help. As she walked out of the courtroom with her boyfriend, she expressed frustration that her management company, Central City Concern, wasn’t keeping up its side of the bargain. She cited nuisance neighbors, broken appliances and clogged toilets. “They’re not fixing anything,” she said.

A spokesperson for the nonprofit affordable housing provider says it can’t comment on individual tenants, but that “all of our [maintenance] requests have been managed in a timely fashion.”

Here’s the state of evictions in Multnomah County:

MULTNOMAH COUNTY EVICTIONS

Three biggest filers of evictions in 2022:

1. Legacy Property Management

2. Stark Firs Management Inc.

3. Hayden Island Manufactured Home Community

Average owed in October cases of unpaid rent: $3,000

Source: Lisa Bates, Portland State University Professor

Cases filed per month:

Source: Multnomah County Circuit Court

Correction: This story misspelled Moe Farhoud’s name.