Last August, in a room at the Oregon State Correctional Institution, a grizzled Robert King, 72, stared into a camera and swore he’d finally changed.

He was no longer the same King who, in 1984, was sentenced to life in prison for the contract murder of a Lake Oswego woman, leaving her grade school-aged daughter without a mom. King was then a 6-foot-1, 220-pound Alabama native, a hustler with a gift of gab who dealt cocaine, provided financial advice to a scion of one of the Northwest’s great fortunes, and generally dabbled in the demimonde.

“I try to make up for everything—on a daily basis—for the wrongs I did to that little girl and the mother,” King said, choking up. “I can never make it up.”

For King, his three hours being quizzed by the Board of Parole was the latest bout in a decade of fighting. He’s fought prostate cancer. He’s fought vaccine mandates. He’s fought the parole board all the way to the Oregon Court of Appeals—twice.

But this time, freedom felt closer to his grasp.

Among other things, two veteran corrections officers testified in favor of King’s parole—because, they say, King has been an exceptional inmate and has more than once saved the lives of their co-workers.

“His present record and actions during his incarceration more than demonstrate that he has been rehabilitated for many years,” said King’s attorney, Venetia Mayhew. “Mr. King wants to go home.”

For the first time in King’s 40 years behind bars, the parole board agreed. His release is scheduled for May.

Not everyone agrees. An hour’s drive north of the Oregon State Correctional Institution, in Clackamas County, prosecutors are alarmed at the prospect of King’s release. “The only thing that stands between Mr. King and further crimes is the fact that he’s well supervised in the Department of Corrections,” says Clackamas County senior deputy district attorney Dave Paul.

“I think he looks at killing a human being like he does one of the wild boars in the outback of Alabama,” says Jay Keating, a former associate of King’s.

The board can still defer King’s release if he presents a “danger to the health and safety of the community.” It will review a psychiatric evaluation of King at a hearing in February.

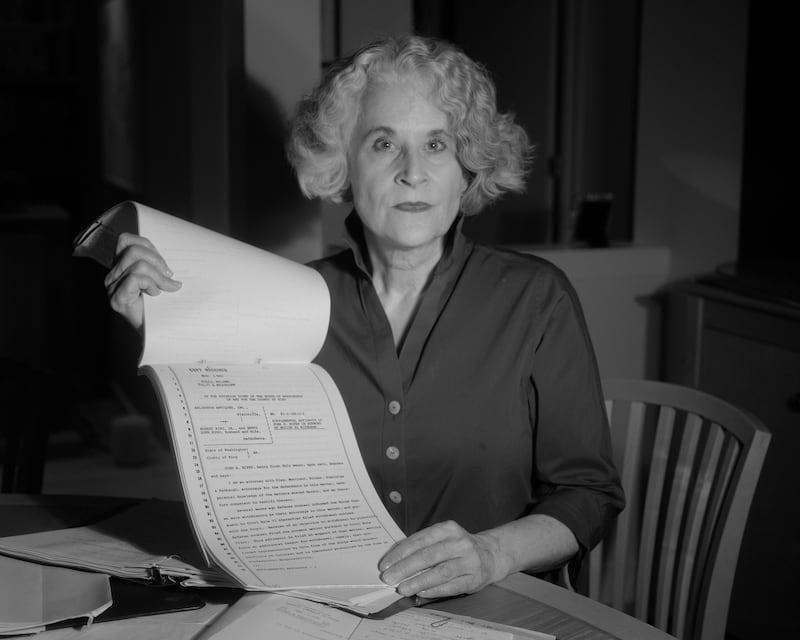

In the meantime, Dorothy Bullitt, a 67-year-old retiree in Seattle, is building a case to stop King’s release. She believes he still belongs behind bars.

Not because she thinks he should still be in jail for his murder of Julie Salter in Lake Oswego or his failed conspiracy to murder a Seattle jeweler.

But because Bullitt is convinced King killed her brother in 1981—and that he wants her dead too.

“It is not about vengeance. It is not about grief,” Bullitt says. “It is just about fear.”

The question presented by King’s case is just how long a sickly old man is worth fearing.

Robert Haden King Jr. was the son of a well-connected lawyer in Gadsden, Ala. King graduated from the University of Baltimore School of Law, but never took a bar exam, and ended up finding work in Seattle in 1980 as an investigator at a local law firm. His wife, Betty, was the daughter of a wealthy King County councilmember and modeled jeans.

After his arrest, reporters pieced together profiles of the “fast-talking, name-dropping” King, a “snappy dresser with a Southern accent” who could occasionally be seen in his father-in-law’s black Rolls Royce and was rumored to carry stacks of bills and handguns that he loved to show off.

Keating, a former business associate, told WW he once asked to borrow $3,000 from King, who handed him the bills and an AR-15 rifle.

King cultivated a gangster persona. He started a rumor that he had fought Nicaraguan guerrillas with the CIA, and would flash a phony government ID. When called to testify in the murder trial of one of his associates, he told a courtroom that he had gone to South America for a cocaine deal in the mid-1970s.

King had a gun room in his Green Lake home’s basement, with “rifles, pistols, stuffed boars and zebra skins,” Keating tells WW.

It’s hard, even now, to distinguish the truth of King’s past from his litany of fictions. King, talkative to the end, was never a reliable narrator of his own life.

Why the lies, an attorney wondered? “Make people afraid of me,” he explained under cross examination while testifying as a state’s witness in 1984. “When I’m on the street taking money from people.”

In late 1980, King was joined in Seattle by Warren Hill, and together they would venture into a series of more serious crimes, some of them bizarre.

The two 30-year-olds knew each other from their Alabama youth. According to a source of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Hill’s mother had worked as the King family maid.

Hill had just gotten out of a Detroit prison on manslaughter charges when King called him up, offering him a one-way plane ticket to Seattle. King picked him up from Sea-Tac airport in his father-in-law’s black Rolls Royce, King later testified in court.

In Seattle, Hill lived in the house with King and his wife. He served as King’s bodyguard and muscle.

King later had this to say about Hill, according to an Oregon Department of Corrections report: “He has a wide range of talents: being a pimp, prostitution, he paints real good—painted part of my house. Cooks real good, barbecues. Washes the dishes real well.”

And: “He’s a good contract murderer.”

King hired Hill for the killing of Julie Salter, a young woman who had moved to Lake Oswego after her divorce. In September 1980, Hill shot her in the head at her Lake Oswego home. Her daughter, Gillian, was a few blocks down the street at Hallinan Elementary School.

Salter was the ex-wife of Jim Salter, a partner at the law firm where King worked. Hill told police he was paid $10,000 to kill her—although it was never clear who paid it.

The motive for Julie Salter’s murder remains unclear to this day. The Salters were in a custody battle. King claimed Jim Salter had ordered the killing, requesting that his ex-wife be raped, mutilated and killed as revenge.

Jim Salter was arrested and put on trial for his ex-wife’s murder but found not guilty, in large part because King, who had pleaded guilty, was the state’s key witness—and he was less than credible.

Salter was acquitted. He died last year. His daughter, Gillian, tells WW she believes the murder was part of an elaborate attempt by King to blackmail her father.

“It’s pretty hard to reconcile how you don’t have your primary parent your whole life because somebody else was desperate for financial gains,” Gillian Salter says.

Two years earlier, in Washington, King and Hill were convicted of plotting an aborted murder of a Danish-born Seattle jewelry dealer, Ole Bang Pedersen, whose estranged wife was romantically involved with one of King’s colleagues.

King was given three life sentences. Two in Washington for the robbery and murder conspiracy, and one in Oregon for the murder of Julie Salter.

King “demonstrated a disregard for others and for the criminal justice system,” Judge Dale Jacobs wrote in his sentencing order, which would put King behind bars, with the possibility of parole after 30 years.

But, Jacobs wrote, “the prognosis for the defendant’s rehabilitation is poor.”

As King received two of his life sentences in a Washington courtroom, in the gallery was Dorothy Bullitt.

The Bullitts are a Seattle dynasty that, over three generations, has channeled a fortune built in timber and broadcast television into Democratic politics and local philanthropy.

They have shaped the paths of states: Their television stations were the springboard for the political career of late Oregon Gov. Tom McCall. The family’s foundation, led by Denis Hayes, a founder of Earth Day, has given away $200 million to environmental causes, and the family has deeded its Capitol Hill estate to Seattle for a city park.

For the past four decades, the family has nursed suspicions that King killed Dorothy’s brother, Ben.

King and Ben Bullitt met soon after the Alabama hustler settled in Seattle. The two shared similar social circles, and Bullitt was attracted to King’s fast life—money, women, cars, drugs.

Ben, a high school dropout, was the black sheep of the Bullitt family. At the time, he owned an antique store downtown and sold weed, according to his sister. But Ben “yearned for the finer things in life,” Dorothy says, and was charmed by King. The con man fashioned himself as Ben’s financial adviser, teaching him how to leverage his family name into bank loans, which Ben used to finance the purchase of a 67-foot wooden yacht named Pegasus in the winter of 1981.

Days later, Ben Bullitt disappeared. Drunk and high on cocaine, he purportedly dove fully clothed into the frigid waters of Lake Washington. His girlfriend attempted to save him, but he slipped through her grasp, she later told police. Ben was presumed drowned.

His family doubted that version of events. Despite a monthlong effort by divers to scour the 200-foot-deep lake, Bullitt’s body was never found—fueling rumors that Ben had survived and fled his debts, or had even been murdered.

In Dorothy’s telling, Ben was drowned by King or his associates and his body spirited away in a seaplane and disposed of in a nearby crematorium.

King has long denied involvement in the disappearance. “[King] denies all scurrilous allegations that have been made about him in the media by the Bullitt family and their associates,” his attorney tells WW.

But Ben’s family long clung to hope that the mystery of his death could be solved, forwarding their theories to police. In turn, the Bullitts’ suspicions infuriated King, who believed the family to be behind his legal woes, according to a fellow inmate at King County Jail who told police about King’s plan for revenge.

That inmate, Kenneth Pendleton, told detectives King had hatched a plan to sneak out a $5,000 murder contract on Dorothy’s father, Stimson Bullitt, in a neighboring inmate’s imitation leather Bible.

Pendleton said King wrote out careful instructions to have Stimson, a prominent lawyer and activist, killed in the basement of the Seattle First National Bank building, where Stimson parked his MG every day on his way to work. Dorothy was the next target.

Prosecutors never filed charges related to the scheme, but it terrified Dorothy. Police handed her and her father mug shots of the suspected gunman and told the two to be on the lookout.

Ten years later, Dorothy says a pair of detectives showed up at her office and told her they’d reopened an investigation into Ben’s death, interviewed King in prison, and concluded that he still planned to kill her once he was released. Police didn’t press charges because they assumed King would be behind bars for life, Dorothy says. Records from that investigation were not included in documents reviewed by the parole board, and WW could not obtain them by deadline.

Four decades later, Dorothy still has trouble sleeping and avoids sitting in a restaurant without a clear view of the door.

“There are a lot of people who feel their lives are in danger if King is released,” she says. But only a few were willing to have WW publish their names.

“The others are still afraid,” Dorothy says.

Four decades after King’s violent crime spree, he says he’s a changed man. “I was a whole different person back then,” he told the parole board, blaming “a total change in personality” brought on by a head injury suffered in 1978 plane crash. “I’m going to be apologizing for it the rest of my life,” he says.

But what ultimately appeared to sway the board was testimony from King’s prison guards, who said he was the best inmate they’d ever had (see “Reversal of Fortune,” page 16).

King could be released as early as May. But that date isn’t set in stone. King has an “exit interview” scheduled for February in which the board will review a psychological evaluation and determine whether King has a “severe emotional disturbance” that could present a danger if he were released.

If that happens, Keating says he’ll buy a gun. Dorothy Bullitt fears he’ll track her down in Seattle. The two plan to submit testimony at King’s next hearing.

“I just want to keep him in prison so I am safe, my family is safe—and for Jim and everyone else who hasn’t come forward,” Bullitt says.

For his part, King has told the parole board he hopes to return to Alabama, mentor at a local church, and keep bees. He intends to live with his brother, who signed a letter in 1994 saying King had a job—and a $35,000-a-year salary—waiting for him at his family law firm.

His brother, Daniel King, isn’t wholly on board.

“I love him so much,” his brother told WW in a phone interview from Gadsden, where he still works as a lawyer for the family firm. But, he added, “he should move to a place where he can start over again and nobody knows him.”

Reversal of Fortune

Why the Oregon parole board changed its mind about Robert King.

The last time Robert King sought parole, in 2012, he was denied. The board found him defensive and aggressive. Its members were unmoved by King’s excuses, finding that his crimes were not “somehow isolated and time-limited.”

Ten years later, a new board came to a different conclusion after reviewing much of the same evidence. It found King is “likely to be rehabilitated” and scheduled his tentative release for May, pending a psychological evaluation.

Here’s what changed in the intervening decade:

KING GOT OLDER

At 72, King is part of an aging Oregon prison population. The state had the highest percentage of inmates over 55 in 2011, according to the Pew Charitable Trusts.

Not only are older inmates more expensive to incarcerate (the state must pay for their health care), they are also less likely to reoffend. And the board is doing a better job taking that into account, says Dylan Arthur, executive director of Oregon’s Board of Parole and Post-Prison Supervision.

“We’re getting better risk assessments,” Arthur tells WW. “As we age, we become generally less risky.”

KING GOT A NEW LAWYER

For some parole hearings, inmates are guaranteed legal representation. The attorney plays a major role, giving opening and closing statements and coaching their client through the interview. In 2012, King was represented by an attorney in Vale, Ore., near the prison where King was incarcerated.

In the intervening years, lawyers at the Criminal Justice Reform Clinic at Lewis & Clark Law School, a driving force in Oregon criminal justice reform, have taken an interest in representing inmates before the parole board. King is represented by Venetia Mayhew, who began taking these cases and encouraging others to do so too while running the clinic’s Clemency Project in 2018. “There were basically no attorneys providing them with the kind of representation that they needed,” she says.

Mayhew was one of three lawyers, including the clinic’s director, Aliza Kaplan, King asked the parole board to have represent him in his petition for a new hearing last year.

Why did King pick them? “We’re good at our job,” Kaplan says.

PRISON GUARDS CAME TO HIS DEFENSE

King came to his Aug. 18 hearing armed with something he didn’t have 10 years earlier: a letter, signed by 16 corrections officers, attesting to his character.

In 2010, King intervened in an assault on a guard and has frequently reported plots by fellow prisoners. With such actions, King “saved four staff lives” and “modeled what rehabilitation is,” states the letter, written in support of a commutation request to Gov. Kate Brown. (She commuted sentences or pardoned convicts in nearly 50,000 cases, but not King’s.)

Two guards testified at King’s August hearing. Gary Alves, a correctional sergeant with 33 years of experience, told the board that King was the “best example” of prisoner rehabilitation he’d ever seen.

King, besides being a frequent informant, did another favor for his prison guards.

In 2021, after Oregon corrections officers sued Gov. Brown in protest of a vaccine mandate, King came to their defense. He filed testimony, arguing that guards would walk away en masse if a mandate were introduced.

“I personally know 41 correctional officers who will resign or be terminated if the vaccine mandate is enforced,” he wrote.

The board does not appear to have been aware of King’s efforts to help vaccine-skeptical guards. It didn’t come up during his parole hearing, and it’s not mentioned in the more than 200 pages of documents reviewed in August by the parole board, which gave WW a copy of the packet with names and medical records redacted.

After WW emailed the three board members present at King’s hearing, asking whether they knew of the favor, the board’s director, Dylan Arthur, responded, “If the information was not in the hearings packet or covered in the hearing, it was not considered.”

Alves initially offered to speak to WW via telephone but stopped responding to emails.