It’s the phone call every parent dreads.

On Oct. 15, 2017, Dan Nichols, an engineer at Boeing in Gresham, raked leaves at his Lake Oswego home. His wife, Kathryn, was inside, preparing to make dinner. The couple were empty-nesters, except for their Labradoodle, Sage. Their daughter Laura, a recent Gonzaga University graduate, lived in Seattle; their son Dave also worked as an engineer at Boeing, in Washington state.

Earlier that day, Dave, then 24, had journeyed to a rock-climbing hot spot in the Alpine Lakes region called “the Enchantments” about 15 miles south of Leavenworth and 160 miles northeast of Portland.

Dave loved climbing. He’d taken a summer mountaineering course at Oregon State University and later trained with the Mazamas mountaineering club in Portland, bagging most of Oregon’s major peaks. A former high school wrestler, he was compact and wiry, with an engineer’s precise approach to setting anchors in rock crevices to ensure his climbing ropes held firm.

It was a warm, dry autumn morning—no ice yet on the granite rock faces that lure climbers from all over the West. “I’d climbed in the Enchantments plenty of times,” Dave Nichols now says.

But that day, something went wrong. Partway up a climb called Orbit on the 1,000-foot rock face called Snow Creek Wall, Nichols fell about 50 feet, shattering his helmet and breaking his neck, shoulder, and bones in his face. He came to a stop hanging upside down from his climbing harness, blood pouring from his mouth. Other climbers, some with medical training, rushed to his aid.

Unable to land in the steep rocks, a helicopter dropped rescue staff who intubated Nichols, preventing him from choking to death. The chopper then lowered a basket to evacuate him and rushed to the hospital.

At his parents’ home, the phone rang.

“I got a call from somebody at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle,” Kathryn Nichols recalls. “They said Dave had had an accident and we needed to come right away. His brain was bleeding.”

Doctors said Dave had suffered a severe brain injury. Even after Nichols’ condition stablized, doctors remained pessimistic. “They said there was no hope, we should consider palliative care and organ donation,” Kathryn Nichols recalls.

The family rejected that option. Instead, they embarked on a five-year odyssey that would expose them to a sliver of the Oregon health care industry that, according to advocates, is uncoordinated, unfriendly to patients, and underresourced. Specifically, experts point to a shortage of inpatient rehabilitation facility beds and coordinated services for patients who have suffered what are called “traumatic brain injuries,” or TBIs.

About 13,500 Oregonians each year end up in the hospital with TBIs, state figures show, and at least 45,000, and probably far more, live with the “chronic, long-term effect of brain injury.” People who have fallen, been in vehicle crashes, been assaulted or shot, or suffered sports injuries are the most likely to have TBIs.

In many states, when patients with a traumatic brain injury leave the hospital, they go to specialty hospitals, “inpatient rehabilitation facilities” that provide at least three hours of intensive therapy a day to help the patient regain function.

But when the Nicholses tried to bring Dave home from Seattle for rehab, there were no beds available.

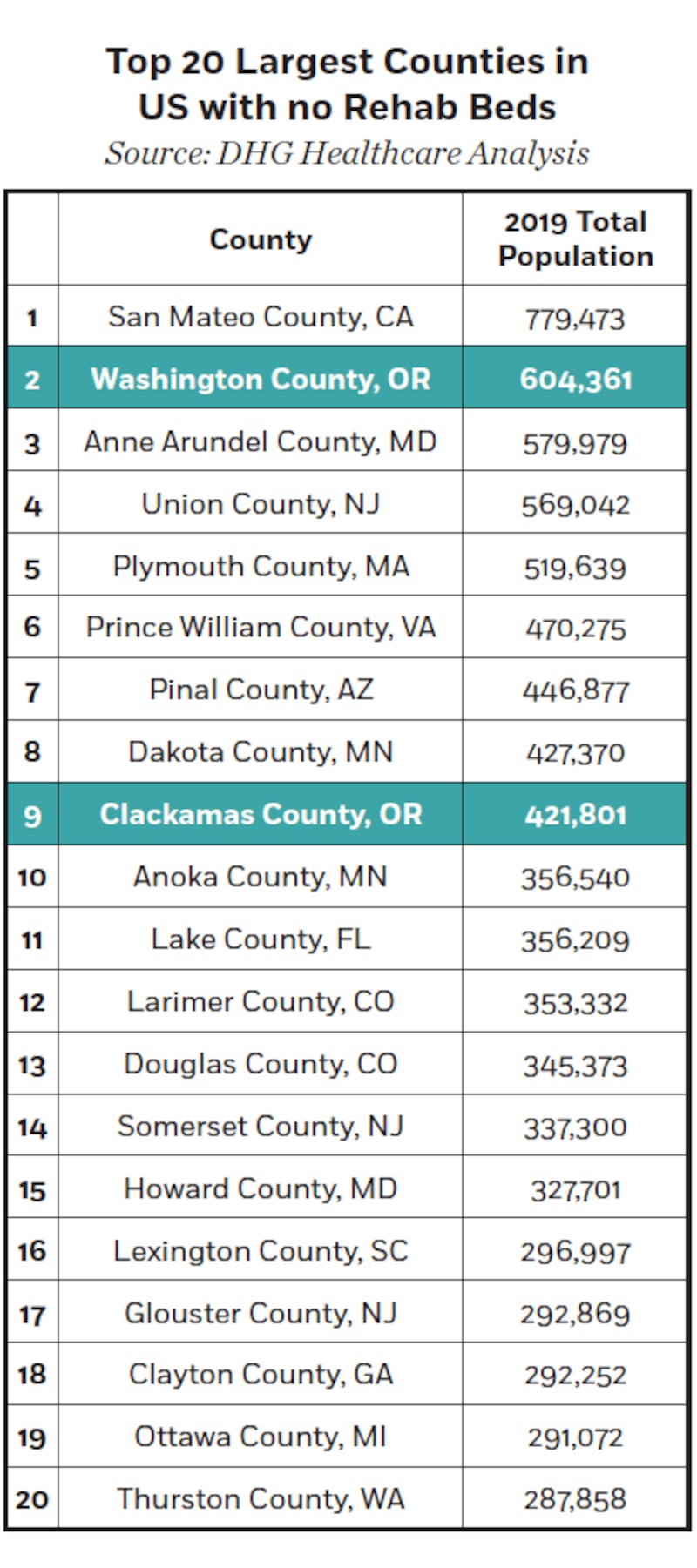

The biggest medical player in Portland, Legacy Health, has not expanded its 36-bed Rehabilitation Institute of Oregon for more than a dozen years, even as the state’s population has grown. Providence Portland offers the only other intensive rehab beds (18) in the metro region. In fact, Washington and Clackamas counties are among the largest counties in the country without a single rehab bed (see table below).

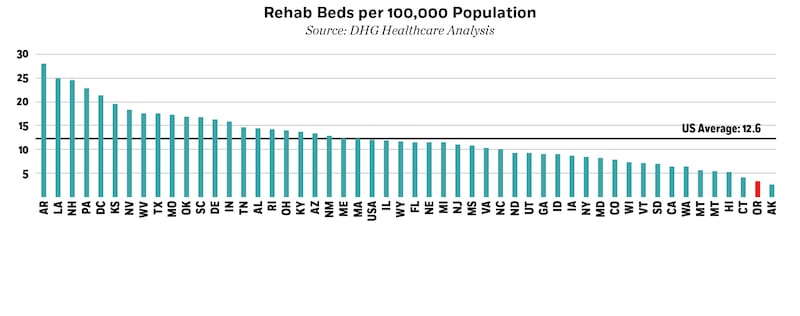

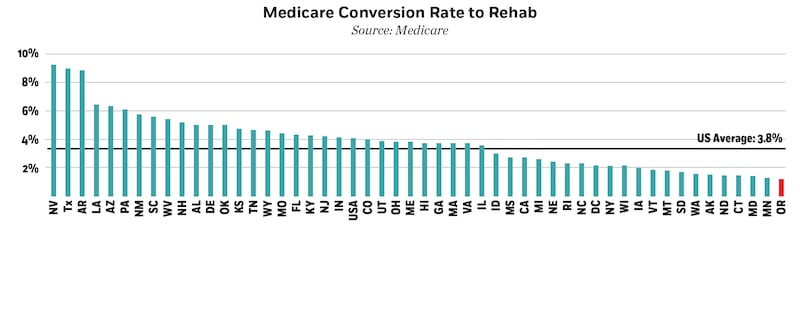

Oregon ranks 49th in the number of rehab beds per capita, ahead only of Alaska (see graphs, right). So the Nicholses had to fly their son from Harborview in Seattle to Craig Hospital in Englewood, Colo., where, for five months, he got the kind of intensive therapy unavailable to him in Oregon.

Coincidentally, not long after Dave Nichols came home from the out-of-state rehab hospital, two rehab hospital companies from the East applied to the state of Oregon to enter the Portland market and expand the number of beds for rehab. But WW has learned that two of the biggest players in Oregon health care, Legacy and the Oregon Health Care Association, which represents nursing homes that serve rehab patients, have spent the past four years blocking the new hospitals.

Richard Harris, former director of addictions and mental health for the state, is part of a group working to expand and coodinate Oregon’s services for people who have suffered TBIs.

Harris says he was unaware Legacy and OHCA are suing to block the creation of additional rehab beds. “I find that incredible and inexcusable,” he says.

In 1971, Oregon lawmakers passed legislation requiring that before a health care provider invested in a significant new program or facility, it must obtain a “certificate of need.” Currently, Oregon is one of 35 states that require a certificate of need before a new facility like a rehab hospital can open. The premise, in the state’s words, is “to discourage unnecessary investment in unneeded facilities and services,” which helps to “control the rapidly escalating costs of health care through planning and regulation.”

Like many good ideas, however, the certificate of need process has veered off track. Nationally, critics from the left (such as the Brookings Institution), the right (the Heritage Foundation), and the U.S. government say requiring new entrants to prove their investments are needed restricts competition, reduces patient choice, and raises costs.

As far back as 2004, the U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission jointly urged states to abolish certificate of need requirements.

“Certificate-of-need laws impede the efficient performance of health care markets,” the agencies said then. “By their very nature, CON laws create barriers to entry and expansion to the detriment of health care competition and consumers. They undercut consumer choice, stifle innovation, and weaken markets’ ability to contain health care costs.”

The Oregon Health Authority, which issues certificates of need, rarely denies them, but the process can be so long and tortuous that it is an effective barrier. Last year, for instance, OHA issued a certificate for a new psychiatric hospital in Wilsonville six years after its initial application. In a state where the shortage of psychiatric beds is the subject of three federal lawsuits and has resulted in emergency releases from the Oregon State Hospital, opponents convinced OHA to add so many restrictions to its approval that the applicant, United Health Systems, walked away, calling the state’s requirements “untenable.”

Five years ago, two companies saw an opportunity to provide more rehab beds for Oregon patients. Both are large, for-profit providers: Encompass Health of Alabama has 153 rehab hospitals around the country, and PAM Health of Pennsylvania has 41.

The companies filed applications with the Oregon Health Authority for certificates of need: Encompass proposed a 50-bed hospital in Hillsboro, and PAM wanted to build a 50-bed hospital in Tigard.

Although they are competitors elsewhere and would be here, each of the newcomers supported the other’s application.

Existing operators in Oregon reacted differently. Portland-based Legacy, a nonprofit that operates six hospitals and more than 70 clinics, and had revenues of $2.56 billion in 2022, objected strenuously to both applications. So did the Oregon Health Care Association, which represents 1,000 members, including about 130 nursing homes.

Legacy disputed the need for additional beds, despite Oregon’s 49th-place ranking in rehab beds per capita, saying in Nov. 4, 2019, testimony that the new facilities would “result in an unnecessary duplication of services and will have a negative financial impact on other providers…with resulting harm to Oregon’s patients receiving Medicaid or charity care.”

Legacy spokesman Ryan Frank says there are enough rehab beds currently.

“In 2019, which is relevant for the timing of the applications, [Legacy’s] occupancy was 73.7% and Providence’s occupancy was only 31.7%,” Frank says. “The occupancy rates for the existing inpatient rehab facilities show that we have significant available patient capacity and there is no need for these projects.”

Phil Bentley, the CEO of the Oregon Health Care Association, says the health authority used bad math evaluating the need for more beds.

“I have all the sympathy in the world if a family is struggling to access rehab care,” Bentley says. “But OHA did not accurately calculate the need for new rehab beds, and now that Oregon has a health care workforce shortage crisis, the importance of getting that calculation right is even more critical.”

Bentley’s association represents skilled nursing facilities, which are an alternative for patients suffering from a TBI. While the level of care is not as high as at rehab hospitals, nursing facilities say their care for TBI patients is cheaper than at rehab hospitals. “Nursing facilities are a more cost-effective supplier of rehabilitation services,” the OHCA said in Nov. 4, 2019, testimony.

OHCA and Legacy worried that the new entrants would strip-mine patients with private insurance or Medicare that pay a higher rate of reimbursement than Medicaid, which covers low-income Oregonians through the Oregon Health Plan.

“If their applications were granted, [Legacy] would continue to serve the vast majority of the most vulnerable patients in our community, while Encompass and PAM take a greater proportion of patients with less challenging medical needs and commercial insurance or Medicare,” Legacy’s Frank says.

The rehab hospitals disputed their opponents’ analysis, arguing that patients at rehabs get more and different kinds of therapy, including physical, speech and occupational, for a minimum of three hours a day. At skilled nursing facilities, they say, patients often get one hour of therapy a day and staff is less numerous and has less training. Some experts agreed.

“Patients do better if they go to rehab—there’s plenty of research that shows that,” says Dr. Nick Bomalaski, who runs a 14-bed rehab program for PeaceHealth in Vancouver, Wash. “They have higher levels of functional independence, higher quality of life, and less of an expense to society.”

With the stakes high, the certificate of need process for the two out-of-state firms dragged on for four years, with Legacy and the nursing home industry opposing approval every step of the way. Finally, in May 2022, the Oregon Health Authority proposed to issue certificates of need to both applicants.

OHA’s Dr. Dana Selover explained in her written order that Oregon not only demonstrably had too few rehab beds, but data showed patients at hospital rehabs had better outcomes. They were half as likely to end up back in hospitals as patients treated at skilled nursing homes. She also found that independent rehab hospitals, like those proposed by the applicants (of which Oregon has none), were cheaper than rehab programs located inside general hospitals.

But Legacy and the Oregon Health Care Association were not finished.

On June 14, 2022, the organizations filed suit in the Oregon Court of Appeals to block both hospitals.

Due to the court’s large case backlog, no decision is likely before mid-2024, and it could take much longer.

Dr. Bruce Goldberg, a former director of the Oregon Health Authority, says he’s not sure the certificate of need process is working as intended.

“The intent was to use health care dollars efficiently and to help improve access,” Goldberg says, “but over the years it has been used to keep competition out.”

Sherry Stock, director of the Brain Injury Alliance of Oregon, says the entrenched players, Legacy and OHCA, are using the certificate of need process to put their own financial interests ahead of what’s best for patients.

“It’s all about the money,” Stock says. “That’s what it’s all about.”

Richard Harris has spent his career in social services, including 29 years at Portland’s Central City Concern, where he was executive director.

Harris says he’s come to realize the massive human and financial impacts of failing to identify and properly treat TBIs.

“The whole system is divided and siloed in Oregon,” Harris says. “There’s no way for a person to thread their way through all the places they need to go. It’s been a problem for a long time.”

Harris says there are thousands of Oregonians whose brain injuries were never properly identified. “TBIs are poorly diagnosed and underdiagnosed,” he says. “The reality is, the longer it goes undiagnosed, the more likely patients are getting the wrong treatment, and so things get worse.”

Unlike 39 other states, advocates say, Oregon offers no central place for TBI patients, who’ve often seen their executive function and organizational skills damaged, to get coordinated services from the state and county agencies that are directly involved.

Harris points to the consequence of Oregon’s lack of resources for people with TBIs: research across the U.S. and Canada among people who become homeless. A Colorado study published last year, for instance, found that in a survey of 115 homeless people, 74% had a TBI before becoming homeless.

Portland, of course, has a disproportionately high rate of homelessness.

“I would say that is a significant contributor to our homelessness rate,” Harris says. “Given the lack of information about services that exist, it has an effect. People with brain injuries just don’t get better by themselves.”

Dave Kracke, a Portland lawyer behind new state laws that safeguard the return to competition and the classroom for children with sports-related concussions, says research also shows TBIs factor disproportionately in histories of people who develop substance use disorder or end up in jail or prison.

“The statistics are staggering,” Kracke says. “One study found more than 70% of the women in prison have a preexisting TBI.”

Kracke, thanks to a federal grant, is now the state’s first brain injury advocate. He worked with Harris and others to prepare legislation for this session that would establish a TBI navigation center within the Oregon Department of Human Services. The idea in Senate Bill 420: to hire coordinators who would streamline access to therapy and other supports.

A recent survey of families such as the Nicholses determined that the average TBI sufferer needs a dozen different services and supports.

“For Oregon not to coordinate those services,” Kracke says, “is just terrible.”

Any structural changes will have to pass muster with the Oregon Association of Hospitals & Health Systems and OHCA, which collectively gave candidates $2 million last year. (OHCA gave $165,000 to Gov. Tina Kotek.)

Legislative leaders and a spokesperson for Kotek say they are not familiar with the certificate of need process but expressed a desire for better outcomes.

“Our health care system is in a crisis and near a breaking point,” says House Speaker Dan Rayfield (D-Corvallis). “We should be evaluating all our existing systems and procedures to ensure they are working to stabilize our health care system.”

After his accident, Dave Nichols shed nearly 40 pounds—and a lot more. At Craig Hospital, the stand-alone rehab facility in Colorado, he relearned how to walk, talk and go to the bathroom. He came home April 20, 2018, six months after his fall.

He’s no longer an engineer at Boeing, but he has progressed to the point that he can live semi-independently in an apartment in his parents’ home.

He continues to make progress. His ropy forearms attest to punishing daily workouts. His balance is better: He can nearly walk unaided.

His speech is slow and a tremor still affects his hands, but he works two part-time jobs as the social media coordinator and a cupcake maker at Sara Bellum, a Multnomah Village bakery staffed by workers with brain injuries.

“I’m trying to help spread the word about our mission and delicious cupcakes,” he says.

“For me personally, things have just been improving,” he adds. “The future still looks pretty bright, still positive. That keeps me motivated to work hard and work at my exercises.”

With special equipment, he’s been able to fish, ski and even scale indoor climbing walls.

His goal is to return to work as an engineer and someday, he says, go back to the Enchantments: “I still am itching to climb outside again.”

Kathryn Nichols says she’s very proud of the improvement her son has made, but she also knows her family is atypical. Dave had excellent health insurance through Boeing and, as a former government auditor, she was better equipped than most to negotiate Oregon’s fragmented health care and insurance systems.

“We know we are among the 1% in the brain injury world,” she says. The Nicholses were able to stay in Seattle, then Colorado, while Dave recuperated, and they can now shepherd him from place to place in the disconnected system of outpatient services scattered across the Portland metro area.

Kathryn Nichols says she and her son have come to recognize the signs of untreated brain injuries in the homeless people they see in their travels. The lack of treatment is a cost both to the injured and to everyone.

“With only limited inpatient rehab services in our community and without support from families like ours,” Nichols says, “many people who suffer TBIs will not have a shot at the kind of recovery Dave has made.”