The Big Number: $22.3 million. That’s how much Metro homeless services bond money Multnomah County budgeted but failed to spend in the first half of the fiscal year.

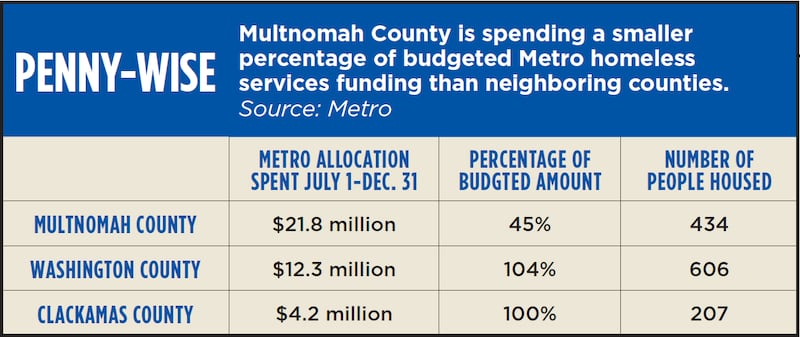

New figures for the first half of the current fiscal year show Multnomah County spent less than half its budgeted funding from the Metro homeless services measure.

Through the six months ending Dec. 31, the Joint Office of Homeless Services reported spending just under $22 million of its allocation from the Metro measure. That’s a lot of money but less than half the amount JOHS budgeted to spend—and less than 20% of the Metro dollars it’s expecting to spend over the course of the fiscal year.

That continues a trend from last year, when the Joint Office far underspent its Metro allocation (“Saving for a Rainy Day,” WW, Nov. 30, 2022).

Sometimes, when governments underspend their budgets, taxpayers appreciate their restraint and fiscal discipline. But with Multnomah County having recently reported record unsheltered deaths, and the city and county still dotted with homeless camps, underspending is not ideal.

“It’s disappointing,” says John Russell, a property investor who owns buildings in the city’s downtown core and in Old Town. “I think it may go back to a disagreement between the city and the county. The city thinks shelters are a first step, but the county disagrees—and it controls the money.”

Denis Theriault of the Joint of Office of Homeless Services acknowledges it spent far less Metro money than planned, in part because of contractor understaffing.

Andy Miller, executive director of the nonprofit Our Just Future (formerly Human Solutions), which provides affordable housing, shelter services, and rental assistance and is a Joint Office contractor, says his organization faces chronic labor shortages.

Amazon and other corporations provide competitive wages for work that can be less challenging than working with homeless or marginally housed Portlanders, Miller says, and housing costs for employees have continually risen faster than wages.

Miller adds that nobody benefits from the Joint Office underspending. “Our hope is that we’ll figure out solutions to open the pipeline for the dollars to flow more efficiently and effectively,” he says.

Voters approved a 10-year, $2.5 billion homeless services measure in 2020 aimed at putting roofs over the heads of people who are chronically homeless, especially those with one or more disabilities.

Each of the three metro-area counties gets an annual allocation based on estimated revenue collected in the county—Multnomah County’s budget for Metro funding is $101.5 million this fiscal year. Metro requires the three counties to file quarterly reports documenting their spending.

The numbers for the first half of the fiscal year show that the other two counties, unlike Multnomah, spent their budgeted amounts. The figures also show that the other two counties were more efficient than Multnomah at getting people housed.

Theriault acknowledges both of those differences. But, he says, Multnomah County set more ambitious goals than its peers in terms of the percentage of its annual budget it planned to spend in the first half of the year. He also notes that the Joint Office is in the middle of rolling out services at the new Behavioral Health Resource Center downtown, expanding a pilot to place people in existing housing, and other programs.

Theriault cautions that quarterly spending numbers will show big variations, but he also says the Joint Office, which has had three directors in the past year, must do better.

“It’s clear something needs to be different,” Theriault says. “There’s a recognition that the housing numbers have to go up.”

Mayor Ted Wheeler is the city’s liaison to the Joint Office, which will get $45 million from the city’s general fund this year (the county will contribute $60 million).

“JOHS makes budget creation and expenditure decisions without city input,” Wheeler spokesman Cody Bowman says. “As such, we do not have enough information to comment. We look forward to continuing our partnership with the county as we work to address Portland’s housing and homelessness crisis.”

County Chair Jessica Vega Pederson says new contracting procedures should improve the situation.

“It’s critical that we address street-level homelessness, and that means bringing increased transparency, accountability and urgency to that work. We are making progress on those fronts — establishing a data systems task force, for example, to identify our key performance metrics. We’re also launching Housing Multnomah Now, which will work to eliminate homelessness in a specific geographic area of our central city,” Vega Pederson says. “We have to get this right and focus our tax dollars both proactively and productively.”