As chief operating officer of the 116-year-old Portland Rose Festival, Marilyn Clint fought through a lot of dark days during the pandemic.

In March 2020, three months before the festival was set to begin, she watched the world shut down. Two months later, she worked alone in her office at Tom McCall Waterfront Park while George Floyd protests and riots raged at the Multnomah County Justice Center three blocks east. In November, the Rose Festival Foundation boarded up the floor-to-ceiling windows in its building.

“I began to wonder if I would see out again,” Clint, 68, tells WW.

But the worst day may have been Oct. 3, 2021, when Russian hackers broke into Rose Festival computers and demanded ransom. She got word of the attack from her IT guy, but she couldn’t go into the office because the Portland Marathon blocked Southwest Naito Parkway.

Things didn’t turn around until Nov. 5, 2021, when the Rose Festival got pandemic relief funding of almost $2 million. Clint remembers the moment like it was yesterday.

“It felt like we won the lottery,” she says. The festival got another $1 million shortly thereafter.

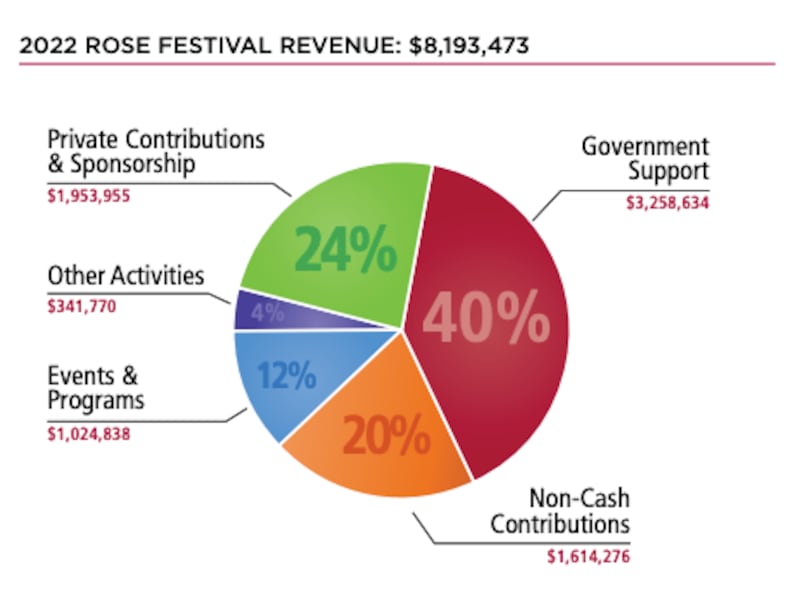

That money made the Rose Festival a ward of the state. In 2019, it got no government assistance and had total revenue—from donations, sponsorships and events—of $7.6 million, according to its annual report. By 2022, government support swelled to $3.3 million out of a total $8.2 million. The pie was larger than in 2019, but a 40% slice came from the government (see chart, below).

In short, the Rose Festival returned last year by the good graces of Uncle Sam. And Clint knows the federal aid won’t last.

“My role is to figure out how to get us back to the point where we’re self-sustaining,” says Clint, who is—ironically—allergic to roses. “If you talk to any nonprofit leader that got pandemic funding, they’ll tell you the same thing: It was great to get that money, but it’s not sustainable money. It all came once.”

The money that kept the Rose Festival alive came from the U.S. Small Business Administration’s Shuttered Venue Operators Grant, or SVOG. But living past this year is going to take more work from Clint and her seven staffers. Clint took over as CEO in September from Jeff Curtis, who ran the Rose Festival for 18 years. A 41-year veteran of Rose Festival management herself, Clint agreed to fight like hell to return the event to breakeven before she leaves in 2025.

It’s a big job, and it all comes down to what the weather is like for three weekends in June. The Rose Festival lost $1.1 million last year, in part because rain drenched the waterfront carnival and doused the Starlight and Grand Floral parades. Tickets and concessions didn’t add the revenue they might have, leaving the festival dependent on sponsorships.

This year, the Rose Festival faces a $699,000 deficit, in part because Spirit Mountain Casino declined to sponsor the Grand Floral Parade, which it had done since 2011. And Spirit Mountain always bought a float (and won “most outstanding” for its 2010 entry).

“They’ve changed their marketing strategy,” Clint says. “They’re really focusing on gaming and not focusing on sponsorships. It was a business decision.”

To survive, the Rose Festival has cut its staff to eight year-round employees from 12, the smallest in a quarter century. Clint took a 14% salary cut in the fiscal year that ended Oct. 31, 2021, to $109,396 from $126,481. Before he left, Curtis’s pay fell to $120,316 from $140,191.

On top of the rising costs of goods and labor, Clint says, the Rose Festival had to buy the company that makes all the floats because it was going out of business, hurt by the pandemic.

Now that the festival is in the float-building business, it’s focused on building floats for Pride parades, a potential growth opportunity (at least in blue states). “It’s just a little part of the business, but someday it could be big,” Clint says.

The Rose Festival’s woes raise the question of whether Portlanders are willing to get off the couch and go into town for a parade.

Clint says they are, and they did last Saturday night. Not only did people line the streets to see the Starlight Parade, but they huddled around the “formation area,” where workers prepare the floats, she says. “People love to watch behind the scenes.” The staging took place at Southwest Harvey Milk Street and Naito Parkway, just blocks from the open-air fentanyl market at Washington Center, but fans weren’t deterred.

Good weather helped get people out, Clint says, and she’s betting on more. The forecast is for temperatures in the 70s and 80s, with small chances for rain.

Clint will be watching the skies, and the box office.

“If I weren’t optimistic, I wouldn’t be sitting here,” Clint says. “But if we’re still losing $700,000 a year, we’ll be out of business in three years.”