Just two months into the launch of Portland Street Response, supervisor Britt Urban encountered a problem mental health clinicians couldn’t resolve.

“Today, we were out on the side of the freeway talking to a woman who was very unwell and dangerously close to traffic and acting erratically,” Urban wrote to the program’s manager, Robyn Burek, on April 21, 2021. “[Police] got there and assumed we would write a Director’s Custody, but we explained we are unable to.”

By “director’s custody,” Urban meant what’s more commonly known as an involuntary hold. Mental health workers authorized by Multnomah County can decide that someone in distress on the streets poses enough of an imminent risk to themselves or others that they may be held against their will. When a social worker writes such a hold, an ambulance takes the person to a hospital for psychiatric evaluation and care.

It’s the first step in a civil commitment, one of the more controversial practices in major cities battling homelessness and worsening mental health crises. In Multnomah County, 258 people may perform involuntary holds. Portland Street Response workers can’t.

That’s because county officials won’t let them.

For two years, PSR leaders have wanted that authority. The county still refuses—and it’s not entirely clear why.

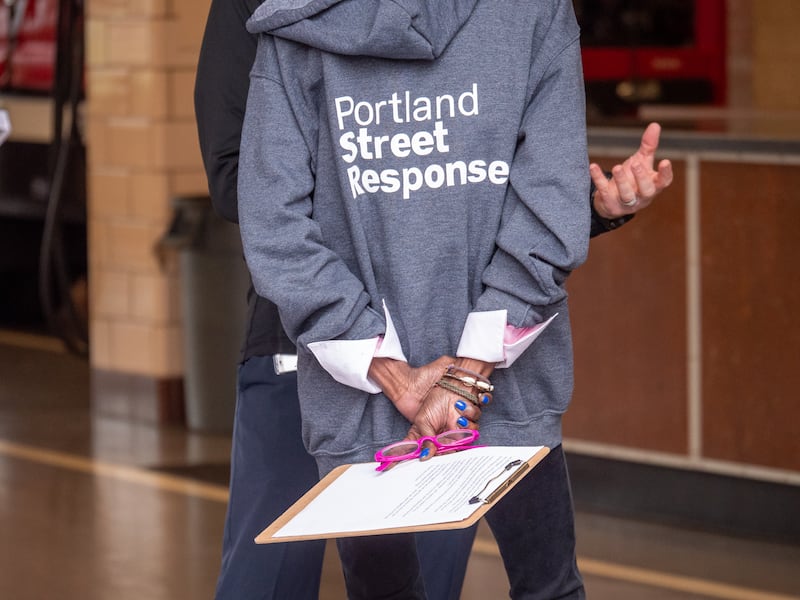

Portland Street Response is both widely popular and politically embattled, thanks to a city commissioner, Rene Gonzalez, who’s reducing its funding and a firefighters’ union that remains unfriendly to it (“Flame War,” WW, May 31). But the dispute over involuntary holds shows other tensions that threaten the program’s long-term prospects.

WW reviewed correspondence within PSR and between program leaders and the county since the spring of 2021. What emerged were two themes.

First, the clinicians who work for the program are divided on whether they should be performing such holds. Some don’t like the optics of working with police to effect what amounts to an arrest. Others argue such holds are sometimes necessary to help the most fragile clients.

“PSR has two camps,” wrote a former supervisor in the program during a recent exit interview obtained by WW. “Those who see themselves as Mobile Crisis Responders and those who see themselves as activists for the houseless community.”

Second, county officials appear skeptical that the newest arrivals on the scene can be trusted to perform work that county employees and contractors have handled for decades. PSR is stepping into the business of social services that the county runs—and the correspondence reviewed by WW suggests some county officials view the program’s role as incompatible with custody holds.

The stakes in this turf war are high. The number of people unable to adequately care for themselves and acting erratically on Portland’s streets raises the question whether more civil commitments should be taking place.

“This is so complex. We are dealing with significant issues of civil liberties and the state’s power to hold someone against their will,” says Scott Kerman, executive director of Blanchet House. “And the other side of the coin is, we have adults who, if they were children, would probably be subject to significant action from Child Protective Services.”

Some 258 people are authorized to perform what are formally known as “director’s custody holds” on behalf of Multnomah County. Those with the authority range from residential facility workers to street outreach workers to treatment facility workers. Overall, the county gives employees from about 10 different county contractors authority to perform such holds.

Project Respond, a decades-old mobile crisis unit partly funded by the county, performed 435 holds last year and has performed 292 holds so far this year. The county did not provide statistics for the total number of holds performed in recent years under the county’s authority.

But Juliana Wallace, senior mental health director at Central City Concern, one of the contractors to which the county delegates hold authority, says her organization has increased its authorized ranks in recent years due to more acute mental health outbursts among its clientele.

CCC added at least three such designees per operating facility, Wallace says, which in turn relieves Project Respond to go out on more calls on the streets. But involuntary holds, she says, are not performed lightly.

“We do holds with extreme caution,” Wallace says. “We have a deep respect for the rights that you’re taking away when it happens. It’s a legal intervention.”

As soon as a hold is written and the person is transported to the hospital, a five-day clock begins for a county investigatory team to determine whether they want to bring a case to a judge, who rules if a civil commitment is warranted. Once the person arrives at the hospital, they’re psychiatrically evaluated. If they meet the criteria for being held, they stay until the county’s investigation is complete. If they fail to meet criteria, they’re released.

Police can write similar “peace officer holds,” but are sometimes more conservative when writing them.

Urban, in her April 2021 email, wrote to Burek that police officers “generally have a more black-and-white assessment of a situation since they are not trained mental health professionals” and that when Portland Street Response has called cops for assistance before, they are “not willing to write a hold because they felt they did not have enough, as the risk was not as explicit as they would need in order to justify it.”

In 2021, Burek urged the county to grant PSR permission to write holds.

“I have tried for several months now to connect with the County around this topic,” Burek wrote in October 2021 to a city director, who then looped in a county supervisor to the conversation.

The county EMS supervisor responded later that day, suggesting PSR workers needed classroom time before receiving such authorization. (Everyone is formally trained by the county before being handed hold authority.) The program never got the county’s green light.

The county would not say directly why it opposes PSR having permission for holds, but health department spokeswoman Sarah Dean says the county is responsible for ensuring that “authority is properly extended and the hold is safe, constructive and defensible and that the designee is held accountable for their actions.”

In other words: legal liability.

“For the agencies that have individuals who [perform holds], they have a whole hierarchy of governance that holds those individuals accountable for those actions,” says Jason Renaud, executive director of the Mental Health Association of Portland. “It’s not a power to be given out lightly.”

Dean says PSR has a direct line to Project Respond, which can perform such holds—and fewer than 1% of PSR calls ended in a call to Project Respond, she adds. “Expansion would require a significant expansion in law enforcement that needs to be present, and expansion in our ability to enroll, train, track and hold accountable all providers. Those resources don’t exist at this time.”

Ryan Gillespie, deputy chief of the division of Portland Fire & Rescue that oversees PSR, says the program has dropped the matter—and hasn’t asked the county for permission to perform holds since the end of 2021. “We may reengage this conversation later,” he tells WW.

But as recently as November 2022, PSR workers were being trained on hold criteria, even though they can’t perform them. And the possibility was once again floated in Portland State University’s December 2022 review of the program, which noted that some officers within the Portland Police Bureau “said that PSR’s values to police would expand considerably if PSR could authorize holds.”

Other officers, the report noted, were less confident.

Police Bureau personnel “warned of a slippery slope that could cast PSR too much into an enforcement role,” the report read, “which is antithetical to their philosophy and purpose.”

PSR’s future is less certain than it was last year. The program’s champion, former City Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty, was replaced by Commissioner Gonzalez this year, who ousted her in last November’s general election and is loyal to the fire union, which endorsed him. In recent weeks, Gonzalez has signaled he’s open to offloading PSR to the county or to a contractor. (Gonzalez tells WW he supports PSR having the authority to perform holds.)

In her original email to Burek in April 2021, as the city fawned over the new program, Urban warned that what she witnessed in its first weeks on the street was just the tip of the iceberg.

“Obviously, writing a hold is a major responsibility, and it should only be done in very specific and limited circumstances (as it is taking away someone’s civil rights),” Urban wrote, “but after being out in the field for just a short time with PSR, I am already seeing the need in our context.”