It’s no secret that Oregon has a housing shortage, but how do we compare with other states?

A new report released Oct. 19 by Up for Growth, a Washington, D.C., think tank that advocates for the thoughtful development of more housing to wipe out the shortage of nearly 4 million homes nationally, shows Oregon is doing a worse job than all but four states: California, Idaho, Utah and New Hampshire.

The report highlights a shift, however: “Between 2019 and 2021, massive new household formation and shifting demand for lower-cost suburbs led to an 11% spike in the housing deficit of non-urban America, officially moving the center of housing underproduction away from large coastal cities to, quite literally, everywhere else.”

One of the case studies in the report describes the affordability crisis in Bend. “Bend may be the Milken Institute’s number five in economic performance among small cities, but it is ranked 179th out of 203 in the number of households with affordable housing costs (Switek et al., 2023),” the report says. “Bend’s median home price hovers close to $800,000, while the area median household income (AMI) is about $74,000.”

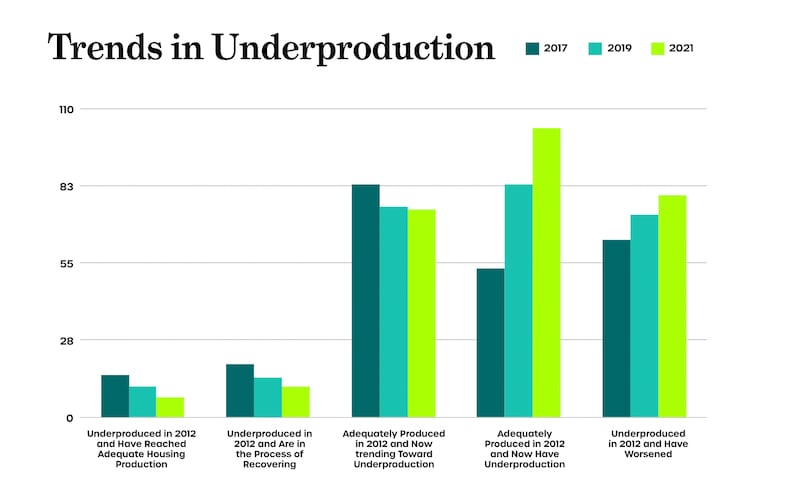

The study, prepared using data from the U.S. Census Bureau, found that underproduction—the difference between the number of housing units required to house everyone and the number of units actually available—has steadily worsened.

Situations vary widely across the country: California is short nearly 1 million homes; Mississippi, only 5,000. (The report, prepared with assistance from Portland-based ECONorthwest, pegs Oregon’s shortage at 87,000 homes.)

The 41-page report includes a wealth of data and charts and looks at the causes of underproduction as well as the consequences: growing rates of homelessness and the perpetuation of racial inequities as Black and Latino families are priced out of home ownership, historically the greatest tool for building wealth. Increasingly, families are forced to move further and further to find affordable housing. That’s in part, researchers found because of policies that limit where multi-family and other more affordable types of housing can be built. Such policies produce a variety of bad outcomes.

“The economic and often racial segregation resulting from exclusionary practices also makes U.S. democracy less cohesive and more polarized,” the report says. “A particularly blatant unfairness arises when restrictive zoning that bars multifamily housing means that workers earning lower wages can provide services in a community but can’t afford to live there.”

And as the numbers show, progressive states such as California and Oregon are experiencing some of the greatest difficulty in developing enough new units.

“Not a single state is providing enough housing for its citizens,” said Mike Kingsella, CEO of Up for Growth. “Policymakers must make the straightforward but difficult choice to prioritize new funding sources that allow for diverse housing types, to invest in construction innovations, and to bolster infrastructure funding despite the risks posed by NIMBY opposition. Only then will we slow the pace of housing underproduction.”

Correction: this post originally linked to and drew from Up For Growth’s 2022 report. WW regrets the error.