When a city is grappling with overlapping and co-occurring substance use disorder and mental illness, a picture can be worth a thousand words.

At a one-day fentanyl summit hosted by the Oregon Department of Justice earlier this month, Central City Concern CEO Dr. Andy Mendenhall presented a slide deck that captured the challenging conditions on local streets.

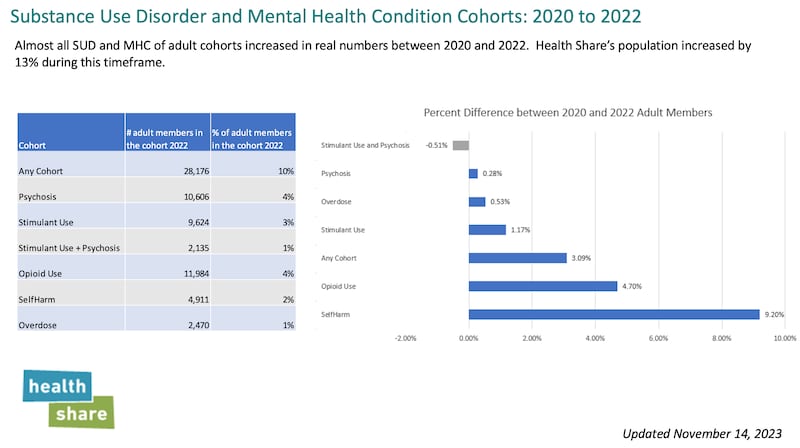

Earlier this year, Mendenhall, whose organization provides a variety of services from basic medical care to affordable housing to in-patient drug treatment, asked Health Share of Oregon to pull data from the claims filed by the roughly 400,000 Oregon Health Plan clients in the tri-county area. Those claims are covered by Medicaid payments funded by state and federal dollars.

Mendenhall’s goal: to gain a baseline of understanding of the number of people experiencing substance use disorder and severe mental illness. Researchers with Providence CORE crunched the Health Share numbers and presented them to Mendenhall, who is now sharing them with policymakers and the public.

Here are three of Mendenhall’s key slides:

The first slide illustrates that as the Medicaid population in the tri-county grew 13% from 2020 to 2022, the reported incidence of psychosis, opioid use, overdose also grew, although not as fast.

Mendenhall says from his vantage point in Central City’s Old Town headquarters, that is surprising.

“I would’ve bet against that, based on what I saw downtown,” he says.

Mendenhall adds that although the incidence of psychosis and various substance use disorders lagged the growth of Medicaid, the loss of hundreds of individual service providers and other challenges such as new, more powerful meth, fentanyl and other durgs and the inability of groups to meet during the pandemic combined to make mental illness and substance use disorder challenges more severe.

“The acuity went through the roof because people had less access to care,” Mendenhall says.

The second slide illustrates the disappearance of beds available at Oregon State Hospital for people who need to be civilly committed because they are a danger to themselves or others.

Historically, officials used such beds to stabilize patients and help them with medication, therapy, housing or other supports. But over the past decade, as the chart shows, the number of such beds has plummeted from about 200 to 13.

Officials now allocate those beds to people who have been charged with crimes but have been deemed unable to “aid and assist” with their own defense. That means many people who might previously have been offered services at the state hospital are left to wander the streets until they end up arrested, lodged in an emergency room (which is often ill-equipped to serve), or worse.

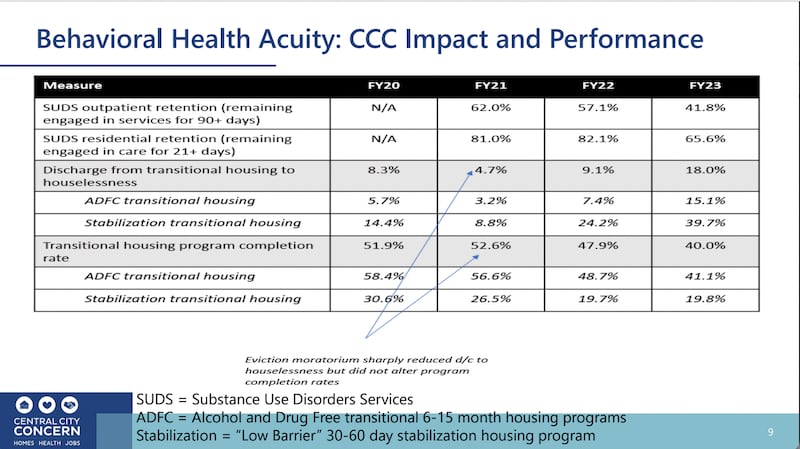

In a third slide, Mendenhall also provided a snapshot of the results of stronger drugs and insufficient beds at the state hospital or in community settings. Central City Concern runs a variety of programs aimed at helping people deal with substance use disorder and also to move from the streets into housing. The chart below shows that the organization is seeing a lower percentage of people stick with such programs over the past three years.

Part of the solution, Mendenhall says, is longer, more intense services. “Many of these individuals would be doing better if they got a residential treatment episode of care for 30 to 60 days,” he says.

Correction: This post originally said that psychosis and substance use disorders increased faster than Medicaid enrollment from 2020 to 2022. That was incorrect. WW regrets the error.