Oregon lawmakers passed a bill earlier this month lowering the retirement age for thousands of public employees—those classified as police or firefighters—based on a strong emotional argument.

As numerous first responders testified in Salem, being a cop or firefighter can be tough at best—wading into volatile domestic arguments; dealing with drunks, overdoses and car accidents; and regularly seeing humanity at its lowest—and dangerous at worst.

“My colleagues in fire…give their all every day. A difficult career choice that is not the easiest to convince people to try,” Karl Koenig of the Oregon State Fire Fighters Council testified Feb. 6. “If you are leading with health information to attract able-bodied people to our profession, you cannot lead with occupational cancer, hypertension, heart conditions, and early death.”

Lawmakers, including state Rep. Dacia Grayber (D-Portland), who is a firefighter in her day job, ran with that argument, saying in effect that first responders have earned some peace and quiet. They did so in the absence of data that shows what police officers and firefighters do in retirement.

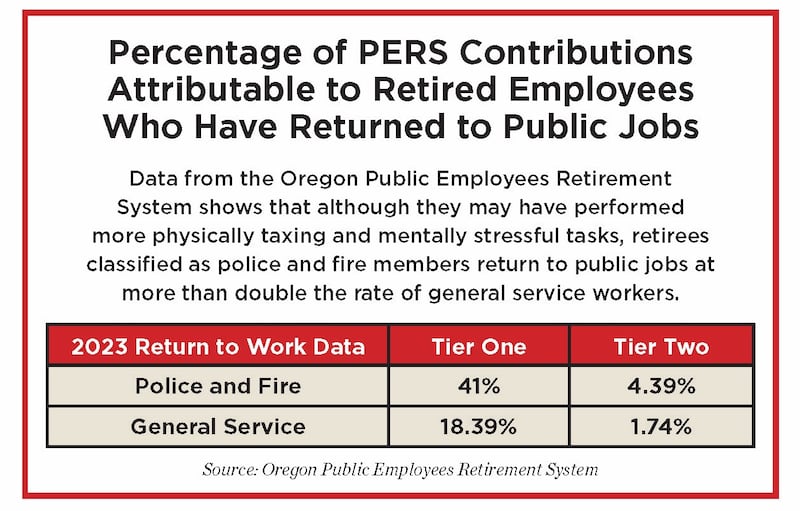

That data, newly obtained by WW through a public records request, shows a relevant fact: Police and fire retirees are far more likely to return to public employment than are “general service” employees—i.e., desk jockeys (see chart below).

In other words, the work may be more challenging, but cops and firefighters are far more likely to return to public employment than are regular public employees. That’s seemingly at odds with the argument that the demands of their jobs dictate they retire earlier.

State figures show that nearly 10,000 pensioners in the Public Employees Retirement System last year worked public jobs after retiring. Although data is incomplete, 45% of retirees who returned to work at state executive branch agencies in 2022 and 2023 were classified as police or firefighters.

Grayber, who chairs the House Committee on Emergency Management, General Government, and Veterans, where House Bill 4045 originated, says she would have liked to have seen the retirement data before moving the bill. She didn’t.

But Grayber says the numbers wouldn’t have changed her mind—nor does she see an inconsistency in lowering the retirement age for people who already come back to work more frequently than desk workers.

Grayber says lowering the retirement age will help agencies deal with chronic shortages of first responders and compete with neighboring states for personnel.

“It is good policy that makes modest changes to current law and improves Oregon’s ability to recruit and retain a portion of Oregon’s workforce that serves the public,” she says, adding that first responders who return to work after retirement may perform less demanding jobs in which they “are not exposed to the same hazards and physical demands.”

State Sen. Brian Boquist (I-Dallas) cast one of only five “no” votes for HB 4045 in the Senate.

He doesn’t buy what he heard. “The argument for early retirement is 100% about burnout, stress and danger,” Boquist says. “Yet they go right back to double dip. Every police retiree I know went back double dipping after they retired.”

The “double dipping” to which Boquist refers used to be frowned upon. The concept was this: Work until you reach retirement age, then take another job—maybe even your old job—while still collecting a full pension.

State law used to cap double dipping, limiting retirees to 1,040 hours, or a half-year’s pay. But as a carrot for pension cuts in 2019, lawmakers lifted that cap, allowing retirees to work unlimited hours for the next five years, ending in 2024.

(They painted returning to work not as double dipping but as a way to reduce the state’s $21.8 billion pension deficit. That’s because employers don’t have to make pension withholdings for retiree workers and instead can pay that money toward the PERS deficit.)

The carrot for retirees grew. In 2023, Grayber sponsored HB 2296, which extended by 10 years permission for retirees to come back on public payrolls for unlimited hours.

That same year, lawmakers added more than 420 deputy district attorneys to the ranks categorized the same as police and firefighters, a designation that already included many others, such as livestock police, liquor license inspectors and Lottery Commission enforcement agents.

Earlier this month, lawmakers not only voted to lower the retirement age for employees classified as police or fire members of the PERS system; they approved a large expansion of that designation—the import of which is that many more employees will soon get a 20% higher pension than general service employees. They added Oregon State Police lab workers, elected district attorneys and, in a new category with the same 20% premium, 911 operators and Oregon State Hospital workers who deal with patients.

And all of those workers (except the 911 operators and OSH workers, who are in a new “hazardous position” classification) will be eligible to retire at 55 instead of 60, a change the Legislative Fiscal Office said would add $110 million to the PERS liability.

“Lawyers should get early retirement?” Boquist asks, referring to prosecutors. “Why not legislators then? Why not bartenders who put up with drunks? PERS is going to become insolvent if Oregon does not change.”

Correction: this story originally said 911 operators and Oregon State Hospital workers would be eligible for the new, lower retirement age of 55. They are not. WW regrets the error.