When the Oregon Supreme Court disqualified Democratic candidate for governor Nicholas Kristof from the 2022 primary ballot on Feb. 17, 2022, the ruling marked a rare setback in a life of relentless achievement.

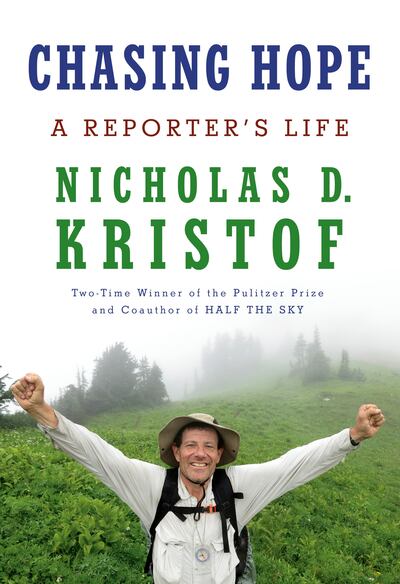

In his new biography, Chasing Hope, Kristof, 65, the longtime New York Times journalist, presents himself as one of those lucky few who ended up where they wanted to be.

“My dream since I was a kid was to be a journalist flying into civil war, covering humanitarian catastrophes, mobilizing a response,” he writes.

Kristof ended up doing that and much more. His path to two Pulitzer Prizes, and just about every other significant journalism award, started on the student newspaper at Yamhill Grade School, wound through the McMinnville News-Register, where he published stories as a high schooler, to The Harvard Crimson and The New York Times, where he has worked since 1984—with one notable hiatus to run for Oregon governor.

He was valedictorian at Yamhill-Carlton High School, Phi Beta Kappa at Harvard, and a Rhodes Scholar, and took first-class honors at Oxford. It goes without saying Kristof probably would have succeeded in a variety of endeavors more lucrative and less reviled than a profession that many people now regard with a contempt they normally reserve for used-car dealers.

“There came a week in the spring of 1983 when I had to choose between Harvard [Law School] and the American University,” Kristof writes. “In a larger sense, it was a choice between a secure career as a lawyer or an insecure career as a journalist.”

Instead of law school, he went off to the American University in Cairo to learn Arabic; he would later learn Mandarin and Japanese as well for foreign assignments. As a reporter, Kristof became a witness to history, reporting on the Communist Party crushing rebellion in Tiananmen Square in 1989 (his first Pulitzer, in 1990), on genocide Darfur (second Pulitzer, 2006), and hitting just about every flashpoint in the world over the past four decades.

His experiences and adventures—surviving a plane crash in the war-torn Congo, being held at gunpoint by soldiers in Ghana—are far removed from the daily lives of most Oregonians, let alone the routine journalism practiced by most ink-stained wretches.

But Chasing Hope is grounded in Oregon, where Kristof’s parents—his father, a refugee from Northern Bukovina, now part of Ukraine, and his mother, an art history professor from Chicago—settled in 1971.

The arc of Kristof’s life in Oregon captures the cultural and economic shifts that reshaped the state over the past half-century. His parents presciently bought their 73-acre Yamhill farm for $65,000. It now produces pinot noir and cider—and you couldn’t buy an acre nearby for $65,000 today. Although he hobnobs with presidents and CEOs, he, his wife, author Sheryl WuDunn, and their three children grow wine grapes and cider apples on the family farm.

Kristof has mined his childhood for material for years, ruminating on the wrenching changes that left many of his Yamhill classmates underemployed, addicted and, too often, dead at an early age. That disconnect between the state’s potential and its reality served as the subject of his previous book, with co-author WuDunn, Tightrope (2020), and fueled his desire to walk away from the Times in hopes of turning Oregon around.

But Kristof’s flirtation with the state’s highest office lasted less than eight months. The lifelong scribe hadn’t read the fine print: As WW first reported in the summer of 2021 (“Article V, Section 2,” Aug. 11, 2021), the Oregon Constitution requires three years’ residency to run for governor, and a plain reading of the law suggested Kristof’s voting history in New York disqualified him. Then-Oregon Secretary of State Shemia Fagan delivered a decision in January, and the Supreme Court upheld her rejection of his candidacy a month later.

That ruling sent Kristof back to his newspaper column—and to penning his memoirs. Here’s his version of what happened. NIGEL JAQUISS.

Excerpted from Chasing Hope. Copyright © 2023 by Nicholas D. Kristof. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Portland had once been a model of urban planning, and in 1992 The Atlantic had published a story extolling the city with the headline “How Portland Does It.” But it now seemed a model of how not to run a city. When officials couldn’t figure out what to do, they announced ten-year plans meant to make a problem disappear. In 2004, for example, Portland adopted one such plan to eliminate homelessness; it sounded good, but ten years later the problem was worse than ever—and then it truly deteriorated. Tents were everywhere in Portland: on sidewalks, on grassy medians between highway lanes, under bridges. Some 22,000 Oregon schoolchildren lacked homes, the Education Department reported. Crime surged as well, so the homicide rate in Portland in 2022 was fifteen per 100,000 inhabitants, compared to less than five in New York City. Criminals in Portland sometimes operated with impunity, raiding stores and walking out with merchandise.

Friends had cars stolen, and we grew wary of parking at the Portland airport for fear that our car’s catalytic converter would be stolen, a common problem.

This wasn’t just a Portland issue, or just an Oregon problem. Up and down the West Coast, from San Diego to Seattle, homelessness had become worse, despite vast sums allocated to address it. All three West Coast states seemed to be bungling housing policy and public safety, in ways that undermined living standards and the quality of life for everyone.

Oregon ranked near last in the country for access to mental health services and addiction treatment, and this in turn affected children. I believe that education is the best metric for where a society will be in a quarter century, and we were struggling. Oregon had the third-lowest high school graduation rate in the country, and one study found it had worse K–12 outcomes than Mississippi.

Governor Kate Brown was stepping down, and there was no obvious successor. A small group of Democratic leaders and business leaders, desperate for improved governance, suggested I run.

One lesson from watching American politics was that the greatest innovation and creativity were often at the state and local level. The federal government was so polarized and constrained by checks and balances that it was usually difficult to conduct bold experiments. In contrast, states were the laboratories of democracy: Blue states rolled out liberal projects (like all-mail voting and relaxed drug laws), and red states tried conservative approaches (like loosening gun laws and tightening access to abortion). If one wanted to tackle national problems, the proving ground was now at the state level.

That’s why another leader who shaped my thinking was closer to home: Tom McCall, a former journalist who served as the liberal Republican governor of Oregon when I was in grade school and high school. McCall may be among the greatest Oregonians ever, as The Oregonian once concluded, for he cleaned up the Willamette River and was a pioneer in his concern for protecting beaches and the environment more broadly. There were a couple of lessons that I took from McCall.

First, McCall grew up in rural Oregon, and his familiarity with both rural and urban areas helped him understand and lead the state. He helped bridge the urban-rural divide in a way that is desperately needed today. I wondered if my farm background might also be an asset in governing, or if I would be dismissed by rural voters as an elitist and globalist. I was frustrated that the Democratic Party was losing rural voters; this started with white working-class voters and was now spreading to Black and brown communities, especially Latino voters. I thought Democrats too often came across as condescending to such voters, disrespectful of their faith, and too quick to preach to them rather than listen to them. I hoped that in Oregon we might provide a model for how to reach some of those voters, many of them culturally conservative, and work with them on improving our collective well-being.

Second, McCall used his journalistic background and formidable communications skills to rally the public behind his goals. He had never been elected to the legislature and didn’t see his role as tinkering with legislation, but rather he framed a vision for the state and then won people’s support for that vision in a way that created a more durable path for change. Could I do something similar with my communications background?

Still, as I looked at McCall’s career, the lessons were mixed. Much of his impact was achieved in his earlier role as a journalist when he highlighted the filth in the Willamette River, and his time as governor was consequential but not always pleasant. He was mortified when he suffered prostate cancer and newspaper readers were given details about the treatment, including amputation of his right testicle. “One ball McCall,” he ruefully called himself. Coverage of his son Sam’s bouts with addiction were also wrenching for him to endure. Then when he ran for a third term, this great man was soundly defeated in the Republican primary—a final humiliation. Did I want to invite such scrutiny and humiliation on myself and my family?

There were other good reasons not to run. I loved my job in journalism, and I felt I was effective at using it to place issues on the national agenda. President Biden phoned me about a column I had written while I was mulling all this (I didn’t tell Biden that I was thinking of diving into politics), and I reflected that I might have less influence on the White House as a governor than as a columnist.

I had two threshold questions: First, could I win? Second, if I won, could I govern effectively and make a difference on issues I cared about? I worried about this second question because I didn’t have political experience. I didn’t know the legislators and county commissioners around Oregon. I wasn’t steeped in state policy. I was an outsider, and while this might have political advantages, I worried that it might impair my effectiveness if I became governor.

The political insiders I consulted took different views of that. Some agreed that it was a minus not to have political experience and a network. Others thought it would be easier to start with fresh eyes. But whatever their views, they mostly thought that Oregon could benefit from someone outside the political class to shake things up. “A governor isn’t the ninety-first legislator,” one business leader told me. “What a governor needs to bring to the table is vision and leadership.”

The backdrop was Trump’s assaults on the democratic system. I had been urging young people to get involved in the political system and work for change, and now I wondered if it wasn’t my turn to walk the walk. For all my love of journalism, I had always thought there was something to Teddy Roosevelt’s “Man in the Arena” speech: “It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes up short again and again.”

But what if I quit my job, ran and lost? I figured that even with an all-out effort, there was only about a 50/50 chance that I would become governor. Teddy Roosevelt had some advice on that score as well, saying of people seeking public office: “If he fails, at least [he] fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.”

One question I immediately faced was whether I was even eligible to run for governor. The Oregon constitution stipulated that a governor had to have been a resident for three years prior to the election. The phrase in the constitution had never been defined. I had had a home on the farm in Yamhill since we built an extension on the house in 1994, and I had been managing the farm and paying taxes in Oregon. We had been spending more time on the farm since 2010, when my dad died, and especially since 2018, when we pulled out our cherry orchard and began Kristof Farms as a new cider and wine business. During the pandemic, we socially isolated on the farm. Yet I also had lived in the house in Scarsdale and had the job at the Times. I had paid taxes in New York for years. Unhelpfully, I had registered to vote in New York and had voted there as recently as 2020 (I switched at the end of 2020). In practical terms, I was a dual resident of both states, qualified to vote in either. So was I eligible to be governor?

You’d think that after interviewing presidents and senators for decades, I might have figured interviews out, but I was quite incompetent with the tables turned. In one of my first interviews, with Willamette Week newspaper, the first question was a softball: Who are some of the people giving you advice? I didn’t want to give their names without getting their permission, so I hemmed and hawed and struggled. I was awful.

One problem was that I tried to answer tricky questions, instead of sidestepping them.

It was staggering how many families were touched by substance use and mental health issues, but stigma kept people from talking about it. I think if we could speak more openly about these issues, we’d have smarter and more compassionate policies. Anti-gay hostility began to melt once people came out of the closet and straight Americans realized that they had close friends who were gay, though this process is far from complete. If people came out of the mental health and addiction closet, maybe we could similarly achieve wiser and more compassionate policies.

Maybe one reason politicians are prone to scandal is that politics nurtures narcissism. I discovered, to my horror, that suddenly it really was all about me. When your circle is incessantly talking about you, and about how great you would be for the state, it helps to have people around you who will deflate you when necessary. Sheryl and the kids took on this responsibility.

One surprise to me was that the campaign professionals had little regard for journalism as a driver of votes. I had assumed that my contacts in journalism and my large social media following would be a huge help. But the professionals said that the real driver was “paid media” (advertising) rather than “earned media” (interviews). “It’s all about paid media,” one said. “That swamps everything else. A good article can help a little bit, but the real impact of news coverage is when you say something dumb. Then there’s a huge downside.”

I hadn’t appreciated the degree to which the political system also amplifies the power of older people. The median age of a primary voter in the United States is fifty-nine. The median dollar comes from a political donor who is sixty-six years old. This helped me, a sixty-two-year-old candidate, but it’s bad for America. When I met groups of potential donors or voters, they mostly were too old to have children in the school system and their concerns were naturally those of retirees and soon-to-be-retirees. If you want to understand why America systematically underinvests in children, it has a good deal to do with a political system that magnifies the power of the elderly.

Despite the strength of the woke left in Portland, and despite the doubts about whether I was sufficiently Oregonian, our campaign was thriving [see “Kristof’s Fans”]. Oregonians, including those in Portland, were desperate for fresh blood and pragmatic problem solving. However progressive you are, you get sick of finding hypodermic needles on your sidewalk. You don’t want your catalytic converter stolen.

We led in the polls, and Democratic powerbrokers began to tell our team that we were likely to win the governor’s race.

Our allies in state government reported that Democratic insiders backing another candidate, Tina Kotek, were putting great pressure on Shemia Fagan, the Oregon secretary of state, to declare me ineligible on the basis of residency. Fagan had a reputation as an entirely political animal, ferociously ambitious, and my removal would reward her political allies and eliminate a potential rival in statewide races. Fortunately, three former Democratic secretaries of state stepped up and publicly asserted that I was eligible, and so did a former state supreme court justice. Fagan herself had listed me twice as a leading Oregonian in the Oregon Blue Book that she published. With her three predecessors all saying I was eligible, we hoped it would be too nakedly political for Fagan to toss me from the ballot. We were wrong.

My campaign flopped in the end, so I’ve been asked if I am embarrassed about it. Embarrassed? Not at all. I believe in big swings, and my life has been about taking calculated risks: As a result, I’ve tried and failed at lots of things. In this case, I saw problems and did my best to tackle them. I’m sorry I wasted the time of volunteers and the money of donors, but I think we did elevate issues like addiction and mental health that needed to be addressed—and I would still strongly encourage all kinds of people to take a risk and run for office.

I may be the first candidate for governor in Oregon who never had a single ballot cast in his favor. But Sheryl puts it more gently. She says that this side of North Korea, I’m the only person to have had a political career and never had a single voter cast a ballot against him.

GO: Nicholas Kristof in conversation with Congressman Earl Blumenauer at Revolution Hall, 1300 SE Stark St., revolutionhall.com. 7:30 pm Thursday, June 6. $42, includes copy of Chasing Hope.