Councilor Angelita Morillo asserts that a better Portland is possible.

It’s a catchphrase used often by the Portland chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America, to which Morillo belongs. By “better,” this is what the DSA means:

Free garbage pickup. Fareless buses and trains. Government-run grocery stores with price control. A downtown where some of the office towers are replaced by subsidized housing. If anybody in those apartments faces eviction, they’re provided an attorney. The residents of those buildings drop their kids off at tuition-free preschools and go to work at jobs with a higher starting wage.

Who pays for all this? Any resident with a high income. What’s high? The DSA won’t put a number on it, but judging by recent ballot initiatives they’ve crafted, it could start at $200,000 a year.

“We essentially have to redesign our entire economy right now,” says Morillo, who represents District 3, which covers Southeast Portland, on the Portland City Council.

Whether they realize it or not, this is the future many Portlanders voted for last fall.

Voters elected 12 city councilors from four geographic districts to set policy. The idea behind an expanded council and geographic representation was that Portlanders would elect a more diverse group of officials—by age, race and professional experience—than ever before. And neighborhoods far from City Hall would have someone speaking out for their interests.

To some extent, the new form of government achieved those goals. It also did something else: It placed four members of the Democratic Socialists of America on the council.

That advocacy nonprofit has long been an agitating force driving Portland politics left, from union drives at Burgerville to new taxes on C-suite executives. But the election of Morillo and her three fellow socialists now means that for the first time in living memory, Portland in effect has two viable political parties—and the second one isn’t the Republicans.

The DSA technically isn’t a party. And city councilor isn’t a partisan office. But the Portland chapter of the DSA says in its own materials that it wants candidates it endorses to “criticize the Democratic Party establishment and put forward the necessity for a socialist party and a rupture with the Democratic Party.”

The “hot socialist summer” is a trend across the U.S. as progressives grow increasingly disaffected by what they see as a Democratic Party incapable of providing a viable alternative to the authoritarian aims of President Donald Trump. In New York City, DSA member Zohran Mamdani is on the brink of winning the mayor’s race.

But no major U.S. city has elected socialists as a third of its city council. Not Seattle. Not San Francisco. The closest is Minneapolis, where socialists hold four seats on a 13-member council.

And six months into the new body’s reign, a dozen City Hall observers tell WW that Portland’s agenda and discourse is largely being driven by a cohesive bloc of leftists on the council—and at its heart are the socialists.

To put the DSA’s clout into perspective, there are more than 56,000 registered Republicans in Multnomah County, yet it’s fair to say those Republicans have a tiny fraction of the influence on City Hall compared to what the DSA’s 2,000 members wield.

Some skeptics say that’s no accident. “In my opinion, this electoral system was designed in part to emphasize groups like DSA that, rather than a broad electoral coalition, represent a slice,” says Doug Moore, who ran a political action committee last fall that was set up by the Portland Metro Chamber.

The conventional wisdom in Portland, shared by Moore and others, is that taxes are too high, especially on the highest earners. Anecdotes and government revenue data both suggest that some people who make over $500,000 a year are fleeing the second-highest marginal tax rate in the nation.

The DSA disagrees. By their telling, the wealthy aren’t paying nearly enough.

“The wealthiest people in Portland should be paying more or their fair share in order to make sure all our services that we want continue to function,” Morillo says. “If we’re doing anything, it’s going to be coming from the people who are making the most.”

It’s little wonder Democrats are nervous. The anxiety travels all the way up to Gov. Tina Kotek, who is trying to undo what the DSA sees as the city’s closest thing to a socialist program: Preschool for All.

“We have a council that’s not afraid to tax the rich,” Morillo says. “There’s pressure from the governor’s office not to look into any of that, and I think there will be a lot of pushback on her vision.”

Councilor Mitch Green has a golf injury. He uses his right leg to propel himself up the City Hall stairs to his second-floor office. He strained his left meniscus on the links in Bend.

Golf is not a typical socialist’s hobby. Bald and bearded, Green does look a little like a cuddly cousin of Vladimir Lenin (a resemblance he winkingly acknowledges with a picture in his office of his head superimposed on Lenin’s body), but he’s more likely to be found drinking beers on the 19th hole than standing on a soapbox denouncing capitalism.

No matter. He’s one-quarter of the group of socialist councilors revolutionizing Southwest Third Avenue.

Green is the plucky middle-aged data nerd of the group. An economist formerly with the Bonneville Power Administration, he produces the reports arguing that Portland’s wealthy ranks are growing, not shrinking.

Morillo is the social media–savvy firebrand who’s known for roasting centrists with witty one-liners on the dais. She proudly displays a “hot socialist summer” poster inside City Hall, the slogan splashed across a picture of Mamdani.

Tiffany Koyama Lane is the smiley former third-grade teacher who wants everyone to get along but is trying to shed her reputation as conflict-averse.

Sameer Kanal is the studious and serious police-accountability hawk who pontificates at length on the dais, and has a master’s in global affairs from New York University and worked in several major cities as a researcher, a consultant and in various roles for Model United Nations.

Together, the four councilors have raised the DSA’s agenda more frequently and more successfully than that of any other interest group in the city.

“No other group who did endorsements or got involved that’s nonpartisan has ever brought together a caucus like this,” says Councilor Eric Zimmerman, a centrist who battles regularly with the DSA quartet. “A standing caucus is not something I’ve ever seen at the city.”

The spring budget season made that dynamic clear as the council, across 35 hours, debated and voted on budget amendments from all 12 councilors, with the most contentious ones around policing and economic development.

The progressive bloc, with the four socialists at its center, moved in formation much more consistently than the centrists, who at times seemed flustered by the bloc’s coordination.

“It was so refreshing to see them move as a bloc, and you can tell it’s driven by their principles,” says Olivia Katbi, a full-time advocate, outspoken supporter for Gaza, and co-chair of the DSA’s Portland chapter. “You can see the other councilors struggling to find their place and know how to vote or what to do. Because I don’t think that they’re necessarily driven by a larger belief system.”

While the DSA has not always succeeded in passing policy, it is shaping the terms of the conversations in City Hall so that the centrists on council are playing defense more often than not.

Kanal proposed increasing, and in some cases studying, a variety of fees, including on golf and vacant apartments, and he sought to create stricter oversight of the Portland Police Bureau’s overtime budget. Morillo successfully routed $1.8 million from the Golf Fund to parks and the city’s Small Donor Elections program, and she helped champion the diversion of $2 million earmarked for the police bureau to fund parks maintenance.

That aligned with a larger distrust of police that DSA leadership had expressed in the spring, when they successfully stalled an effort by the Portland Police Association to join a larger labor guild. Morillo spoke soon after at a DSA panel, calling for the police to “submit to a truth and reconciliation commission” before gaining admittance.

The Police Bureau eventually made its budget whole, and the parks bureau kept its new funding. But the Portland Metro Chamber, the city’s chamber of commerce, spent weeks lobbying to find $2 million for the bureau, which PPB ended up finding in its own budget.

Another target of the DSA: how the city approaches economic development.

DSA co-chair Katbi testified in support of Green’s May proposal to strip Prosper Portland, the city’s economic development agency, of its $11 million in annual funding from the city. Since he took office, Green has been critical of Prosper Portland and its checkered history of gentrification in neighborhoods where it launched urban renewal districts. Katbi testified that Prosper Portland has a history of “directing public funds for unaccountable private profit-making.”

Green’s proposal failed, but not before Prosper Portland executives were caught badmouthing him in a group chat, leading Mayor Keith Wilson to demand the agency’s director step down.

There’s a reason the socialist caucus almost always moves in lockstep.

The four councilors have a standing monthly meeting with a committee of the Portland chapter of the DSA. It’s the only external political group that holds regular meetings with a third of the council. The labor unions don’t do it. The Portland Metro Chamber doesn’t.

That’s a remarkable influence for an organization that has a budget of less than $70,000 annually and just 2,000 dues-paying members. (To be sure, far more Portlanders who aren’t members believe in the group’s vision.)

It’s also a sea change. For decades, the lobbying groups with the most traction at City Hall were the labor unions and the business lobby, represented by the Metro Chamber. Environmental groups and nonprofit coalitions scored occasional wins.

Meanwhile, the DSA floated around the perimeter of City Hall. Former City Commissioner Amanda Fritz recalls the DSA being “kind of a fringe group, as far as I can remember.”

Chatting with WW on a bench in Peninsula Park, Katbi agrees her group lacked influence. “Nothing was possible with one sometimes-ally on council,” she says. “There was no way we were going to get anything passed.”

Much of the DSA’s energy focused on ballot measures, partly because Oregon makes it relatively easy to place a measure on a ballot with signatures, which is exactly what the DSA is good at. In 2020, after gathering signatures for a universal preschool measure, the DSA dropped their idea and instead helped champion Preschool for All, the Multnomah County program funded by a marginal tax on high-income earners that aims to provide a free preschool seat to any family that seeks it.

It was the quintessential socialist policy: a government providing free services on the dime of the wealthiest Portlanders.

In 2023 the DSA tried again, crafting a ballot measure to impose a .75% tax on capital gains to fund free legal services for anyone facing eviction. Opposition picked at two major flaws: It failed to exempt withdrawals from retirement accounts or exempt sales of homes. The measure suffered the worst rejection in three decades of local ballot measures: 4 in 5 voters said no.

Longtime lobbyist Amy Ruiz says the DSA wasn’t taken very seriously because they had ideological aspirations but no chops for how to write a good policy or where to get the money from to pay for the thing they wanted. “You can’t just wish it was there,” Ruiz says.

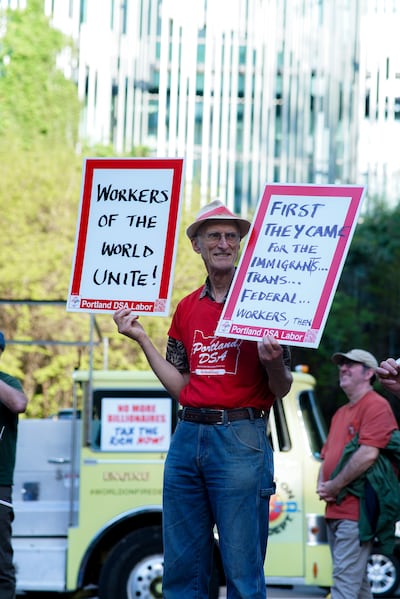

Still, the DSA’s signature red shirts became a common sight at rallies for Palestine and the picket lines of the Portland Association of Teachers’ strike in 2023. The DSA has overlapping views both on local policy and on international issues like the war in Gaza with the teachers union, which is in turn the most powerful interest at the school board. PAT president Angela Bonilla has spoken at DSA events, and Councilor Koyama Lane got her start in politics as a PAT organizer.

The DSA spied an opportunity in November 2022 when Portland voters approved an overhaul of city government and elections, expanding from five to 12 members elected in districts. Ranked choice voting meant that any candidate who received 25%+1 vote would be elected—a far lower threshold than for any other office.

In a March 2023 blog post, the local chapter said the government overhaul “presents an extraordinary opportunity for Portland DSA to disrupt the capitalist municipal order.”

It endorsed two candidates—a narrow focus, compared to other interest groups that gave a lukewarm stamp of approval to a dozen office seekers. DSA volunteers knocked on 10,000 doors for Green and Koyama Lane. Both won, as did Kanal, who was also a chapter member.

On the drizzly afternoon of March 15, Morillo, wearing red pants, a red jacket, and a red scarf and a swatch of red lipstick, walked down the steps of City Hall to join a “Tax the Rich” rally outside. Morillo said she was joining the DSA.

“This was us stepping up into more adult politics,” says Portland DSA co-chair Brian Denning. “And I expect the Metro Chamber is concerned that their influence is waning.”

Green and his fellow councilors say they’re not beholden to the DSA, but their values and policy goals often align. The DSA doesn’t give Green “marching orders,” he says, but it has plenty of input.

“Their intention was to never organize to get me in office and then walk away,” Green says. “I haven’t experienced this yet, but the expectation is that if I do something way out of line with the values of the organization, I’m going to hear about it.”

The four councilors are expected to abide by the chapter’s candidate requirements, Katbi says. Among them: candidates must meet with a new Socialists in Office Committee regularly.

“We want to put someone in office who is going to bring DSA with them to office,” Katbi says. “Our councilors are DSA. So what they are doing is DSA, until further notice, unless we say it’s not.”

So what are they doing?

The DSA launched the Family Agenda, a new policy platform, in April. They want council to pass a Renters’ Bill of Rights, which would require landlords to offer more relocation assistance, ban nonpayment evictions if the tenant is a teacher or student during the school year, ban evictions during extreme weather events, and “establish a right to counsel in eviction court,” among other provisions. (Five councilors—Councilor Jamie Dunphy and the four socialists—signed a campaign pledge to pass it.) The chapter also wants the council to increase the rate of its CEO tax. They plan to door-knock in support of the Parks Levy renewal this fall.

While it’s not written in the agenda, the socialists clearly look askance on any power structure they believe is weighted to favor established interests. That helps explain why the DSA councilors have questioned who Council President Elana Pirtle-Guiney gives the microphone to (see sidebar here), and why they helped lead a disastrous campaign to freeze $64 million in funding for nonprofits aiding children, saying the grants process was inequitable (see sidebar here).

And unlike the council’s centrists, who fret endlessly about the state of downtown, the socialists think the emptying of office towers is a feature, not a bug.

The U.S. Bancorp Tower (better known as Big Pink) just sold for $45 million, down from its $372 million price tag in 2015. Green is unworried.

“Buildings being sold for pennies on the dollar is healthy because then it takes it into someone’s balance sheet that’s fresh and new and their cost basis is lower,” Green explains, “so they can charge lower rents.”

And what about the city losing some of its property tax revenue due to steeply discounted prices of office high-rises? “Some property tax revenue is better than no tax revenue,” Green says. “I’m not interested in policies that try to protect the absentee owners to make them whole.”

Indeed, the DSA’s vision extends to a wholesale overhaul of the current political system. It’s a vision in which capitalism largely doesn’t exist. Executives would give up much of their income every single year so the city can fund free garbage service, a fareless transit system and city-run grocery stores. National anchor tenants in downtown’s high-rises would leave, allowing smaller businesses to move in. The city would buy up properties and atop them build thousands of units of affordable housing.

Koyama Lane, for example, is interested in charging a fee to commercial property owners that have vacant properties. She’s heard some of these owners might be intentionally keeping spaces vacant to receive tax breaks.

“There’s a possibility that’s happening,” Koyama Lane says. (Local governments do not in fact offer tax breaks for vacant spaces. But when a building has lots of vacant space, its market value drops, which in turn lowers the property tax.)

Koyama Lane sees Block 216, the Ritz-Carlton tower, as an example of developers exploiting the city. “I view the Ritz as a very big bummer,” she says. “Developers didn’t want to put in affordable housing, so they paid a fee [and didn’t perform]. How do we hold developers accountable?”

Some small business owners are wary.

James Armstrong runs three eye care clinics in District 2 and ran for City Council in the fall. He says he’s concerned the council is getting too caught up in debates about economic class.

“We have a lot of large issues to tackle that are going to cost money,” he says. “And when we talk about socialism versus whatever the opposite is, it’s an argument over where the money is going to come from. But we’re not some hotbed of huge wealth, so there might not just be that coffer to pull from.”

He asks, “So then what? Are we going to get stuck in this stalemate of the morality of who pays for it, or are we going to have a council that focuses on finding solutions?”

Portland also has a new mayor: Keith Wilson, a buttoned-up freight executive. Wilson is unwavering on his goals: build 1,500 shelter beds by the end of the year and spur housing development, in part by waiving system development charges for developers seeking to build housing. Though the DSA has historically railed against any measure it perceives as offering a handout to developers, it declined to comment on Wilson’s agenda. That may be because City Hall sources tell WW that at least a few of the socialist councilors are open to the SDC waiver.

Wilson declined to comment.

In fact, the socialists will have to defend their policy achievements not only from boardrooms but also from the state’s top Democrats. One Dem in particular: Gov. Tina Kotek.

Kotek, who spent much of her political career as a darling of organized labor, has increasingly expressed concern that local tax policies are eroding Oregon’s economic base. The top target of her ire: Preschool for All.

The DSA hails that Multnomah County initiative as the first time Portlanders went all-in on a program built on socialist values: taxing the wealthy to provide subsidized child care and early education that benefits working parents and kids in low-income households. The program is funded by a tax of 1.5% on income over $125,000 for single filers or $200,000 for joint filers, and an additional 1.5% on income over $250,000 for single filers or $400,000 for joint filers.

Kotek says that burden is driving high-income taxpayers out of Oregon, robbing the state of much-needed revenue. She spent much of the spring trying to convince Multnomah County Chair Jessica Vega Pederson to pause collection and reduce the tax rate, given that revenues have far surpassed projections and mostly remain unspent.

“If Portland does not rebound in the way we think it can,” Kotek wrote to Vega Pederson in June, “the downstream impacts on our economy will end up costing our most vulnerable and lowest income Oregonians the most.”

Vega Pederson demurred.

Late in the legislative session, key Democratic lawmakers introduced a bill amendment that went further: It would ban Multnomah County from collecting the Preschool for All tax or establishing another like it.

When Morillo saw the amendment drop, she responded immediately. “My god can these clowns ever stop clowning?” she asked on Bluesky. “We get it! You’re obedient dogs to the business class! Lick their boots some more, I think you missed a spot!”

The amendment died in committee. But Morillo is still girding for battle and questions the sources who tell Kotek taxpayers are fleeing.

“If your data is explicitly coming from the people that don’t want to give up their wealth, that needs to be more heavily scrutinized,” she says. “I think that’s who [Kotek] meets [with] regularly and who’s in her ear.”

Instead, she says, she trusts an analysis Green conducted of tax return data in June that show the ranks of high-income people in the city are growing, not shrinking.

Katbi casts Kotek’s concern as the revenge of the plutocrats. “They’re trying to shut down PFA because Jordan Schnitzer wants them to,” she says. “Because [Kotek’s] rich friends are mad about it.”

Kotek’s spokeswoman Elisabeth Shepard says that “the suggestion that the governor’s desire for a well-rounded and sustainable tax base is for any purpose other than the functionality of services in Multnomah County, and the future prosperity of the region and our state, reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of what’s at stake in this conversation.”

The fight over Preschool for All is the core of the split between the DSA and the Democrats. The governor sees the socialists as a threat to the state’s economic recovery. In the eyes of the DSA and the socialist councilors, Kotek and Democrats would rather appease the rich than help the poor.

Morillo points to Kotek’s strong urging of local governments in 2023 to impose no new taxes for three years. “That’s an agreement we didn’t agree to,” Morillo says of the council, and particularly her socialist colleagues, “because we just got here.”

Moore, who runs the political action committee United for Portland, which was set up by the Metro Chamber, says he thinks the “socialists are trying to take over the City Council and turn it into an ideological showcase for the rest of the country.” The chamber’s aim? “To stop DSA from taking over the council.”

It’s still unclear whether Portland’s shift to the left, in an era when many of its peer cities are moving to the center, is an accident of a new elections system or a reflection of where voters want the city to go. But that will become clear soon. Three of the four socialists—Green, Koyama Lane and Morillo—represent Districts 3 and 4, the two regions that will hold elections in 2026.

That means Portlanders can no longer express surprise about the results of the last election. They either want the revolution or they don’t.

Morillo says the socialists have an advantage: They’re the one group delivering for the people the new government is designed to elevate. “You can say you care about all these disadvantaged groups,” she says, “but if you’re not doing anything to rectify their economic situation and you’re listening to the power brokers at the Metro Chamber, then you don’t really care.”