This story first appeared in the March 16, 1981, issue of Willamette Week.

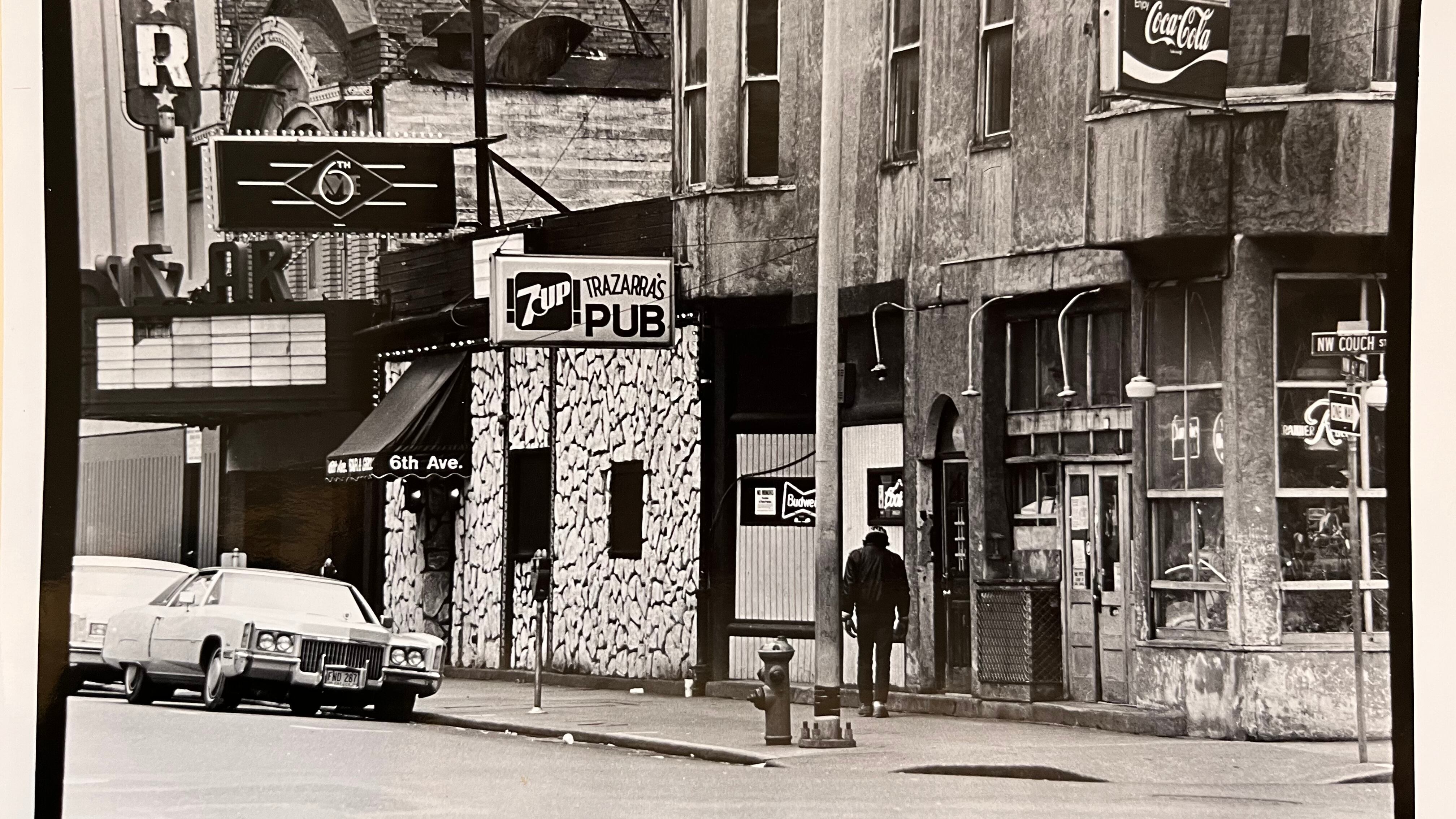

Walk down Northwest 2nd Avenue, past the boarded-up Pomona Hotel, the For Lease signs on Couch Street Gallery, the vacant storefront on the corner of Couch, the empty shops in Space 117. In Collector’s Cabinet, owner Lee Sprague is typing a letter in a store empty except for a host of petrified beetles. They’re for sale. In The Nor’wester Bookshop, Phil Hubert tamps his pipe and fiddles with the volume on the radio in his quiet shop. Across the street, at the end of the day, the till doesn’t even hit $100, and another shop owner walks home mulling over what it would be like to take a part-time job, or to start wholesaling, or to move into Clackamas Town Center. Because it feels as if Old Town is shutting down for good.

But check Old Town’s pulse with the Planning Bureau, the Development Commission, the Landmarks Commission, or the Naito brothers, who own most of Old Town. They’ll call this period a slump, a slide, a cycle, a slowdown, a perceptual problem that’s bound to turn the corner

in five years. When the Northwest Natural Gas complex is built. When light rail runs up First Avenue. When the U.S. Bank Tower anchors the edge of the district. When Baloney Joe’s moves over the Burnside Bridge. When the economy improves, the weather gets bad, the transportation center opens, the preservation money rains down.

They’re all right. From a planner’s point of view, the pace of restoration in the Skidmore-Old Town Historic District is indisputably healthy. In the spread of small, 19th-century buildings that stretches from the waterfront west to 3rd Avenue, and from Oak to Everett, two major rehabilitation projects—the Porter and Haseltine buildings—were recently completed; two—the Blagen Block and the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association Hall—are now under way; a bunch of others, including Erickson’s Bar and Import Plaza, will start alterations any day.

Bill and Sam Naito, the principal movers behind most of these projects, are optimistic, pointing out that the limited amount of developable land in the city virtually guarantees that Old Town will be a success. As landlords, the Naitos are blamed by the merchants for much of their trouble, but Sam Naito is plainly realistic. “The small merchants are undercapitalized. They aren’t able to promote themselves. When you deal with a fickle public, the law of supply and demand is what rules. If a retail store lasts 10 years, I’d say they’re doing very, very well.”

Developers are happy, too. After a false start with the Daon Corporation, Northwest Natural Gas is ready to break ground in June for the first phase of the $200 million Pacific Square project. With more development planned for vacant lots throughout the historic district, things look pretty chipper.

They’re not so chipper, though, in the existing shops. Couch Street Gallery and Space 117, each of which housed a group of small shops and restaurants, are both down to single tenants and going begging. Three more shops will be leaving “before the summer,” according to the owners. Even a few encounters in Old Town make it clear that business is bad, foot traffic is down, and the mood among the merchants is sour. Sure, the economy is aching, they admit, and specialty retail shops are usually the first to feel it. But in Old Town, the bitterness runs deeper. Shop owners charge that the city, the Naitos, and the press have all lost interest in Old Town: that the area’s problems—transients, parking, distance from downtown—and aging faddishness lost the city’s attention to the Transit Mall, the Naitos’ to Galleria, and the press’ to the next big thing. Financially, few can comfortably absorb a business failure. What’s worse, they say, is the feeling that they tried to bring something special to the city and weren’t supported.

“I’m sure the area will come back in five or 10 years,” says Grant Raddon, owner of Windplay. " I just can’t wait any more. If I was still 25, maybe I’d do it. I want to make a living. If someone wants to subsidize me for my pioneering efforts,” he adds with a rueful smile, “fine.”

For most of the merchants, the bitterest pill is realizing that the era that wooed them away from conventional careers to stake out their own corner of the counter-culture is over. And that while their peers bought and patched up crumbling houses in risky neighborhoods and came out ahead, they took a gamble with commercial gentrification that could backfire both ways. Either the area will fail, and the merchants will be left legally bound to worthless leases, or it will succeed so wildly that rent will soar beyond their reach and they’ll be out in the cold again. Few can even dream of buying their buildings (only one merchant in Old Town has managed that), and, without property, many feel that they can never really benefit from their work to transform the district.

“Everything I saved for 10 years is right here,” sighs Rob Artman, owner of Kringle and Claus. He’s one of several shop owners who are hanging tough and hoping that increased development will bring hordes of consuming office workers to Old Town. " I used to think it would be great if they’d just funnel all the office workers down here once a day to spend money,’’ he laughs. “But those lawyers and accountants aren’t the older generation anymore. They’re my contemporaries. I guess I’m pretty optimistic about the long range. It’s just a matter now if I can hang on that long.’’

Funky but chic

Given that jobs are now the hottest commodity next to gold bricks, it’s hard to believe that only 10 years ago people were throwing over their careers to set up shop in Skid Road. Raddon was a physics professor at Lewis and Clark, and before that Cal Tech, when he left to go looking for social change. He ended up running a kite store. Artman taught high school; he now sells Christmas decorations. These aren’t apocryphal scare stories about PhDs driving cabs, but only a few tales of countless people whose particular siren in the ‘60s was the ground floor of an abandoned warehouse, a crumbling dockside, or a vacant shell of brick, where they could run their own businesses, be their own bosses, and sneer at the malls and office towers.

The first generation of these businesses catered to the few who’d brave old neighborhoods looking for head shops, “mood” ring stores, and anything to do with leather or candles. A few coats of paint later, shrewd developers raised the rent, and the now hip strips were revamped and rechristened Seattle’s Pioneer Square, Monterey’s Cannery Row, Vancouver’s Gastown, Chicago’s New Town, Portland’s Old Town. Every business in the districts enjoyed the first blush of faddishness. For a few years in the mid-’70s, it seemed as if these inexperienced, under capitalized, barely even marginal businesses could do no wrong.

“In the summer, people used to just come down here to just be here. This was the place to be. You could just feel it, feel the trend,” recalls Sam Pishue, owner of Jazz de Opus, one of the first Old Town taverns.

Portland’s Old Town was luckier than most. In many cities, including Vancouver, B.C., and Sacramento, city planners tried to capitalize on the trend. The original residents were moved out and massive amounts of money were spent on cosmetics in the space of a few years, jacking up rents that drove out the original businesses and left the areas as regimented, sterile, and phony as Disneyland.

“Lots of cities went in willy nilly with public improvement,” says Ted Schneider, Portland Development Commission project coordinator. “I know it looks like we’re slow, but a lot of those things can be premature.”

If the unfortunate irony is that the Old Town vogue will have run out of steam by the time the facelift is finished, the deliberate care taken with the area’s restoration is well reasoned. In 1978, the Skidmore-Old Town Historic District was singled out as a National Landmark, one of the few urban areas to receive that designation. This protects the buildings, forcing development to meet preservation guidelines that put a damper on runaway gentrification. And although single room occupancy housing for Burnside residents has dwindled, landlords in the area haven’t systematically run the transient and elderly poor out of the Old Town area, virtually guaranteeing that the district would never take off with the well greasedchicness of Greenwich Village or West Hollywood.

There’s also the dominance of the Naitos in the area. Of the Skidmore-Old Town District’s some 20 blocks of land, the Naitos—with the Skidmore Development Co., Direct Imports Inc., Norcrest China, the H. Naito Co. and H. Naito—account for five and a quarter blocks; their holdings are concentrated in the district’s Northeast corner, between the waterfront and 2nd Avenue and Southwest Ankeny and Northwest Davis streets. Because so much of the district’s renovated, usable commercial space is in Naito owned buildings. Old Town has become almost an urban company town, suffering or succeeding by dint of their attentions. Until the Naitos sneeze, says one merchant grudgingly, the city can’t blow Old Town’s nose.

Cool metro

Through the window in his office atop Import Plaza, Sam Naito can watch cars whizzing over the Burnside Bridge into the section of town he can rightfully call his own.

“The least of my worries is Old Town,” he says, smiling. “We are very optimistic about this area.” And well the Naitos should be: Twenty per cent of the developable land in downtown is in Old Town, and even if the economy flattens a trinket store today, the law of supply and demand means the Naitos can’t lose.

So far, they’ve given few people cause to wish they would. They’ve bought a large number of buildings, but, rather than sitting on them while they appreciated, the Naitos have restored them one by one. Nor are they content to sit on their own pioneering reputation: recently they purchased Erickson’s Bar at Northwest 3rd and Burnside, and plan to rehabilitate it. Except for the Naito’s Couch Street Fish House, it will be the farthest west Old Town developers have ventured. The Naitos have also submitted plans to the city that will restore whatever charm they can find to their rather ordinary looking Import Plaza headquarters.

Among city officials with a stake in the area, the Naitos’ reputation is sterling. “You can say whatever you want about them,” says one Planning Bureau manager admiringly, “but the Naitos deliver.”

Their genius, too, has been in striking a deft balance between Old Town’s clashing factions—the merchants and the local community of pensioners and transients. After finishing a number of retail renovations, the Naitos turned their attention to a number of low income housing projects in the top floors of Old Town buildings, thereby appeasing the growing resentment among service agencies who want to protect the area’s housing. The merchants, who had benefitted from the first round of restorations, could only grumble.

For all the accolades awarded the Naitos, their dominance in the northern half of Old Town has its drawbacks. For one, it has meant that most state preservation money has gone else where, since the Naitos, if anything, project an impenetrable aura of freewheeling free enterprise. About 30 per cent of Oregon’s federal preservation money—which is meted out in grants

to help historic projects—comes to Portland; most of it has ended up in the Yamhill Historic District, which constitutes barely half the size of the Skidmore Old Town District.

“Yamhill didn’t have the private support, and each building was owned separately,” says John Tess, state Historic Preservation grants manager and historian. “In Skidmore Old Town, the Naitos carry the ball. We felt we didn’t need to give money to the area because they would take care of it.”

For their part, the Naitos are perfectly happy to keep it that way. “We don’t want to be dependent on the city,” Sam Naito says firmly. " I don’t think we should use tax money for this sort of thing. That’s why there’s only a minuscule amount of public money in this area.”

A powerful vacuum

More worrying is the fact that when the Naitos drop a pebble, all of Old Town ripples, and when they don’t, it’s eerily still. One Development Commission official, who admits he’s “heartened” each time a non Naito building crops up in Old Town, blames the area’s doldrums on lack of attention from the Naitos.

“The Naitos were, and still are, terrific visionaries,” he adds. “Individually, I don’t think they’ve lost personal interest in the area, but there’s just not the collective energy there anymore.”

A merchant who expects to bail out of Old Town before spring is more cynical. “For a company town, the Naitos’ influence has been fairly benign. But, benevolent or not, they are the dictators here. If they don’t exercise strong leadership, it’s awfully hard for anyone else to.” Other projects—Galleria and their 302 apartment complex, McCormick Pier—have diverted the Naitos’ efforts, many merchants complain; Old Town, with its tiny shops, persistent friction with the Burnside community, and wilted glamour, isn’t exciting to the Naitos anymore.

Sam Naito flatly disagrees. “We don’t prioritize. It’s just typical concerns—our Galleria tenants think we spend too much time on Old Town.” However, he agrees that Old Town is fundamentally more troublesome.

“In Galleria, everyone is our tenant, and it’s much easier to push things through. They have their own advertising fund, they have large tenants. The problem with Old Town is that it’s fractured, it’s full of struggling, firsttime entrepreneurs, it caters to fickle tastes, it’s difficult to organize when so many merchants here aren’t our tenants.”

Sam Naito reaffirms the brothers’ commitment to stick with small shops and to stand by their offer to match any promotion money from the merchants (something they don’t do for Galleria), and hints at promotions they will foot entirely to give Old Town a boost. They’ve also bought three old trolleys to use as shuttles on the proposed 1st Avenue light-rail line, and are repairing the double-decker bus that used to run from downtown to Old Town.

The bus service stopped three years ago, as merchants note angrily when they accuse the Naitos of neglect. Neglect is probably not quite the right word: The one thing on which the Naitos have built their success has been in paying attention to things. It is true that they don’t depend on Old Town exclusively: besides Galleria, McCormick Pier and the Dekum Building, they’ve opened 14 retail stores around the state. They’ve run Old Town cleverly, signing only short leases, which means they can alter them as the area develops; building in sliding rents, which take percentages of the businesses when profits are up; charging low rent but making no improvements inside the shops. It’s a business venture that can only succeed for them. But when their tenants’ wallets wear thin, resentment is rife.

“I realized too late,” says one former Naito tenant, “that I was being used.”

How not to have clout

The Naitos are, after all, just landlords. In many cases, they’re barely that—in many of the buildings, retail space is rented on a master lease to someone else, who in turn leases to individual shops. As everyone, from the Naitos to city planners and the merchants themselves, agrees, the shopowners have never managed to organize well enough to have any muscle at all.

Ask around, and you’ll pick up the pattern quickly: Nearly every Old Town merchant “used to be involved’' in the Old Town Merchants Association, and almost all of them gave up because they couldn’t afford the time, the money to hire help at their shops, or the discouragement when nothing ever seemed to happen.

“It’s so hard to get people motivated,” says Kringle and Claus owner Artman. “I could have spent two or three days a week on promotion, or running to City Hall to complain. I just couldn’t do it.”

Each small merchant, it seems, took a turn at hustling for the association, got burned out and became bitter. As a result, even the smallest problems, like getting proper locks on sidewalk dumpsters or repairing street lights, never seem to get resolved. To add to the frustration, the new, larger stores that came to Old Town more recently, like Oregon Mountain Community and The Kobos Co., don’t consider the association significant enough to support. Consequently, these companies have gone about solving their problems individually, using cash the small stores don’t have to advertise, and clout to wield with the city.

For all their stiff independence and disdain for more traditional merchants—”We’re not,” sniffs Collector’s Cabinet owner Lee Sprague, “shopping mall kinds of people”—what the small Old Town merchants seem to want is exactly what shopping centers are all about. Strict hours, compulsory membership in the association, joint promotions, civic attention, a public relations director. The same store owner who gripes that the Naitos treat her more like an employee than a tenant cheers their plan to build association membership fees into their leases.

Room to move

The surviving merchants view the enormous office structures planned for the quaint old district with bright anticipation. Now the word is that the original Daon project slated for the gas company’s property was “marvelous”; that the city, fighting to keep the monster from gobbling up the historic district, was just “harassing the developers.’’ Now that the project is back on line, with Hayden Island Inc. pitching in with the gas company, the merchants are following its financing tribulations with as much concern as they follow their own.

The reason, of course, is that they see it as the anchor the area needs, to bring money and traffic back into Old Town. One Pacific Square—the only part of the project that is almost certain—will be a 13 story office tower with ground-floor retail space. It will house 500 gas company employees and have room to lease for about 500 more workers. Where those 1,000 people will eat lunch, buy cards, and while awaytheir lunch hours is the bet that’s holding the merchants fast for now.

“It’s just two years away,” says Pishue of Jazz de Opus. “If you can hang on that long. Those who can hang on are going to reap the benefits.”

Joseph Smith, vice president of Northwest Natural Gas, realizes that the merchants are counting on the development. “We considered moving downtown, or to a suburb. Or staying. We have a good neighborhood, and good neighbors,” he says. “What’s good for us is good for them. All these new people are going to leave money here somehow, whether it’s on bubble gum or in a bank in the area.”

Maybe the vision of dancing cash registers is so alluring that the merchants have buried any concern that the project will alter forever the Old Town they dream of—an area of unique small shops, loads of foot traffic, cheap rents and long leases. No merchant adds “and a 13-story office building” on the end of that list, let alone the five and-a-half block development with hotel, more office buildings, and convention center that is planned to be the full extent of Pacific Square. Yet when developers proposed a variance allowing the tower to cross over the historic district’s boundary at full height instead of keeping a half block buffer at fewer stories, no one from the Merchants Association yelped.

Certainly, if the gas company building enlivens the area, it will reward the merchants’ tolerance. But more than a few observers fear that the last laugh will be on the shopkeepers. “The gas company building is a watershed project for the area,” says Oliver Larson, partner in the public relations firm of Hayward/ Larson/Hartfield Inc., and former president of the Portland Chamber of Commerce. “But it could very well be too big a development for the area.’’

Too big because it will bring cars, a large building that will sit empty each

night, and, inevitably, higher rent. Although the merchants admit that their rent is likely to soar, they maintain that business will soar faster, and the rent increase won’t matter much. Unfortunately, that is rarely the pattern. If the pressure to develop really grows, the rent will shoot up until the weak businesses are weeded out and replaced with more stable shops with a wider appeal.

“They should have come out in favor of the social-service agencies,” smiles Michael Stoops, director of the Burnside Community Council and Baloney Joe’s, an emergency shelter facility whose presence in the neighborhood has bedeviled merchants. “They may be excited now about the new offices moving in. They don’t realize it, but they’ll be squeezed out, too.”

The squeeze is on, at least on the drawing board. Construction on the 39-story U.S. Bancorp tower at the corner of Burnside and Southwest 5th Avenue is expected to begin this spring; the Transportation Center, which Tri Met estimates will serve 20,000 people daily, is planned for the eastern edge of the district; Natural Gas people are increasingly optimistic about completing all of the 2.2 million squarefoot, $200 million Pacific Square, which would be the largest private investment in downtown Portland. In its full bloom, it would have office space for 5,400 people.

Out on the street

These are tremendous figures, but the merchants are less daunted by them than they are by the number of transients on the street. " A lot of businesses feel like they can’t make it, and they’re tired,” says Pishue. “Tired of the transients, and tired of fighting about it.”

Tired, too, of feeling like the bad guys because they want to run a trinket shop on Skid Road. “This is where I get into a real problem,” sighs Artman, who considers himself pretty liberal. “Society has an obligation to homeless people. But I want to survive, too, in what I’ve chosen to do.”

The police, merchants, and even Stoops agree that the people on the street these days are younger and more aggressive. Even though the crime rate hasn’t noticeably increased, the perception that it has is undoubtedly one more reason Old Town’s vogue has run its course. But while many merchants cite their travails with street people as a primary reason to leave, the very agencies they blame for attracting transients to the area are leaving, too. Frustrated by its mistaken identity as a transient service organization, Northwest Pilot Project, an agency that serves the elderly, is moving downtown; negotiations are under way to consolidate the Burnside Consortium into a multi service center on the far north tip of the district; and Baloney Joe’s, which lost its lease in favor of a Chinese bakery, is moving to the east end of the Burnside Bridge on April 1.

The joke, says Stoops, is on Old Town merchants who have wanted so badly to get rid of Baloney Joe’s, because the people who can’t, or won’t, cross the bridge will now be out on the streets. “The situation might even get worse down here,” he adds. “We have the only public rest room, which will be gone when we go. The real drunk, crazy people probably won’t make it across the bridge to stay inside and play cards, and the merchants won’t have us on call if there’s trouble.”

The fact is that Stoops and the merchants are mutually sick of one another, and, whatever the outcome, it’s a separation both sides welcome.

“We didn’t lose, though,” Stoops says, grinning. “We’re still here and they’re going out of business.”

A store owner who left Old Town, blaming Stoops and his clients, sees the question of the transients as nothing more than a passe liberal issue. " I used to give money to every panhandler that came in here,” she recalls grimly. “I used to care. But, listen, when you’re in business for yourself, bleeding hearts are out of style.”

Cashing in

Specialty retail stores everywhere, not just in Old Town, are hurting—Johns Landing, Belmont Square, even Galleria, are feeling the pinch. For that matter, Old Town is still vital compared with its counterparts around the country. Seattle’s Pioneer Square has been declared nearly dead by the city, the banks, and the developers. The expensive, gussied-up Gastown in Vancouver, B.C., is moribund. The hit list is long and sobering, from Sacramento to Chicago.

There’s more than a flicker of hope, though. Portland’s pokiness about development has meant that Portland could watch other cities make their mistakes first. And Portland has the Saturday Market, which has been a solid attraction for years. Learning from others’ mistakes has helped gain Old Town more credence among lenders and planners, who have watched with dismay the frantic pace of turnover and decline in other Old Towns. Though it’s true that former Chamber of Commerce President Larson says the group was largely apathetic towards Old Town, figuring it would simply take care of itself, most planners believe there is hope for healthy development.

Much is planned for Old Town. A North of Burnside study by the Planning Bureau is under way, which will recommend continuing present land use policies and a $50,000 annual capital improvement program, with coordinated design, street furniture, and uncovered cobblestone streets. On May 10, the city will begin installing special street signs in both the Skidmore Old Town area and Chinatown to help define them as special districts. Chinatown itself, a stone’s throw from Old Town but until now remarkably unconnected, is also beginning to stir with new projects, and there’s hope that the two districts will work together.

Although a few projects have failed recently (most notably the renovation of the New Market Theater, which was considered the most important single project in the area), city planners and developers adamantly disagree with the merchants’ complaint that the city has washed its hands of Old Town.

“The city is slow to show its support,” says Richard Meyer, principal planner for the North of Burnside study. “But it’s very committed to the district. I know it doesn’t seem like it on the street, but there are a lot of people excited who want it to work.”

The question is, on whose timetable and at what price? The optimism at City Hall certainly hasn’t reached the storefronts yet, and more than one store is packing up to head across Burnside or has closed for good. The few that remain may reap the benefits of the coming developments or, like children in a chocolate vat, be drowned by the thing they think they want so much. For all of them, hanging tough or leaving bitterly, losing Old Town means losing something a lot bigger than the store.

“Everything I ever owned and believed in,” says Pishue, surveying the quiet afternoon customers in his restaurant, “is right here on this corner.”