Developers could break ground as soon as March 1 on the nation's tallest all-timber highrise, thanks to a innovative building material hailed by Oregon's lumber industry and Gov. Kate Brown.

Related: Timber Towers or Clean Air? Oregon Gov. Kate Brown's Big Priorities Don't Go Together

Boosters of the innovative product—cross-laminated timber—say it offers something for everyone: the potential to revitalize the rural Oregon timber economy and the potential to be friendlier to the environment than the building materials such as the concrete it replaces.

But now a group of leading environmental groups are raising questions about that last claim—and they are taking their argument to one of the new building's leading funders—the city of Portland.

Critics say the 12-story Framework building, which will be in the the Pearl District and include 60 units of affordable housing, relies on manufactured wood products that are not subject to sustainable harvest standards established by the Forest Stewardship Council.

"Without such a requirement, the City of Portland may be encouraging the already rampant clear-cutting of Oregon's forests," write a who's who of Portland environmental leaders in a Jan. 29 letter to Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler.

The complete list of who signed the letter to the mayor: Audubon Society of Portland conservation director Bob Sallinger, Bark executive director Rob Sadowsky, Center for Sustainable Economy president John Talberth, Oregon Wild conservation director Steve Pedery; Oregon Physicians for Social Responsibility executive director Kelly Campbell and Oregon Chapter Sierra Club conservation director Rhett Lawrence.

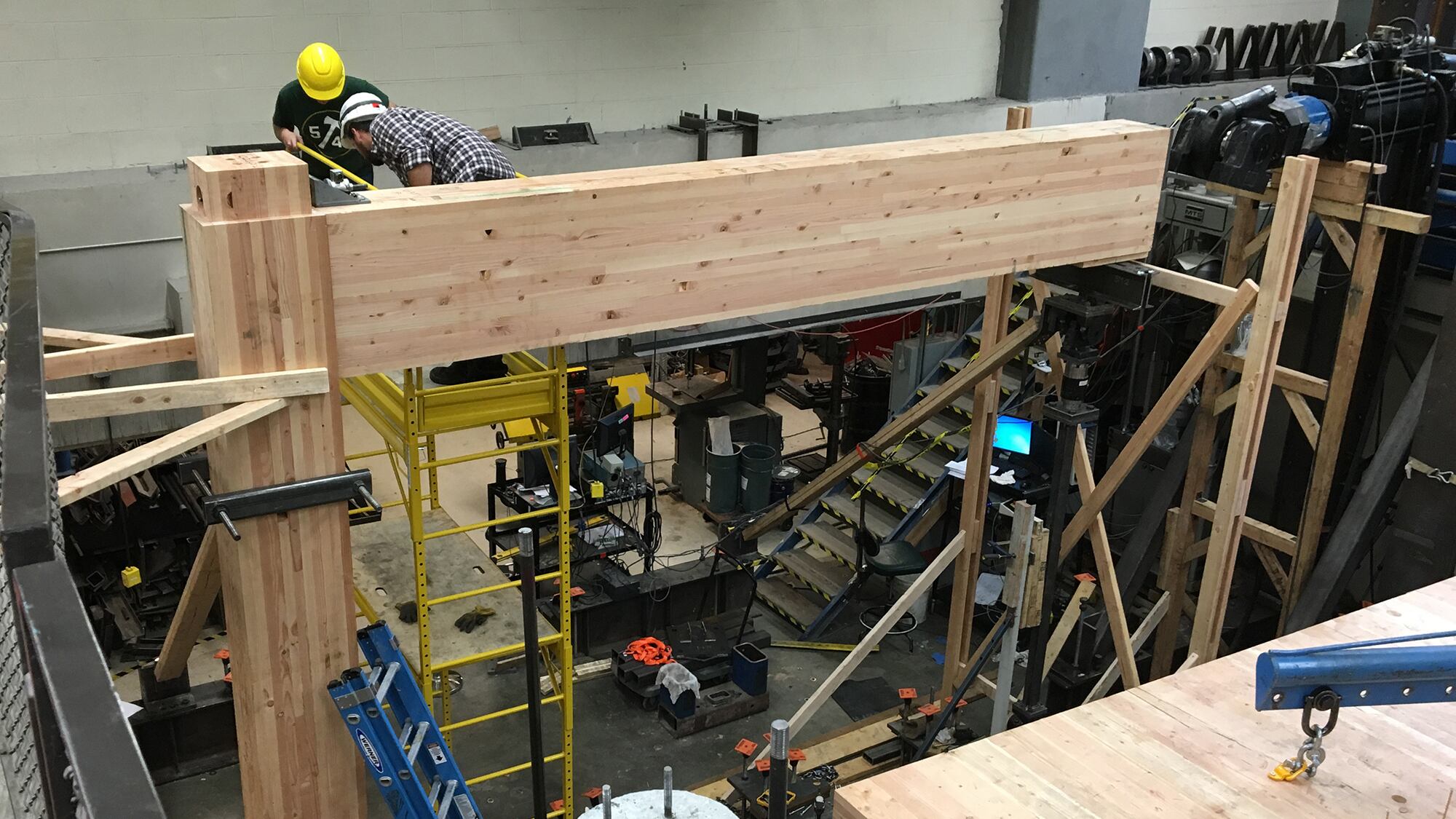

Cross-laminated timber is created by gluing together smaller boards to make large panels that can replace concrete and steel in a building's structure. Because the component parts do not need to be large, younger trees can be used to make CLT.

"Promoters of CLT argue that if large beams and construction materials can be made from small diameter wood, such products could alleviate pressure to log mature and old growth forests on public lands," the letter states.

"However, CLT can also be sourced from clear-cuts on state, federal, and private lands. In fact, because it can utilize smaller material than traditional timber construction, it may provide a perverse incentive to shorten logging rotations and more aggressively clear-cut. Shorter rotations mean more frequent clear-cuts, more mud and silt running into rivers, and more applications of herbicides."

Clear-cutting may not be the only potential environmental risk from CLT:

"Like any other industrial activity releasing potentially harmful chemicals, CLT production facilities must strive to eliminate or minimize the release of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and other pollutants into our air," the letter says.

The mayor's office confirms they received the letter and says they are reviewing it.

A project in North Portland, called Carbon 12, where condos are on sale for $1.5 million on North Williams Avenue, also used CLT.

The city has faced previous questions about Framework's cost: $651.43 per square foot, according to the countywide housing authority Home Forward, which is a partner with Portland Housing Bureau on the project.

Related: Portland's Celebrated Wooden Tower Comes With Another Big Price Tag for Low-Income Housing

"As the letter states, we are not opposed to CLT as a technology, but right now it is Oregon's version of 'clean-coal,'" Oregon Wild's Pedery tells WW.

"It is often said that what coal mining is to West Virginia, clear-cut logging is to Oregon, and I think that is on full display with this issue. Unless more is done to ensure the wood actually comes from sustainable sources, and that the mills producing it minimize toxic emissions, CLT will actually make environmental problems worse, not better."