As a sign of how far Portland's transportation priorities have shifted, the battle at City Hall is no longer about how many spaces developers must create for cars—but how many for bikes.

Currently, the city requires 1.5 bike parking spots per unit in new residential developments in inner Portland.

The City Council will vote this summer whether to expand bike parking requirements for private developers.

The proposal would expand the geographical boundaries for developments required to have 1.5 bike parking spots per unit for residential buildings. And it would require more spaces than are currently available—a number calculated by square footage—for commercial and retail buildings.

The new requirements would be Portland's biggest step in years toward increasing the slice of commuters who travel by bicycle. Supporters say it's a critical part of reducing carbon emissions.

But increasing bike parking conflicts with another civic priority: lowering housing costs. If passed, the requirements could restore some of the construction costs the city has tried to mitigate during the housing boom by slashing requirements for car parking.

The cost of adding bike parking spaces is, of course, a fraction of that for car parking spaces: A bicycle parking spot costs as little as $200 to add to a building, while auto parking spots start at $10,000.

"It might cost the developer, but for the household who is able to reduce their car-owning expenses, it will be a huge benefit," says Jillian Detweiler of the Street Trust, a transportation nonprofit supporting the proposal. "[Cycling] won't work if we don't provide the infrastructure to support it."

Chris Smith, a member of the Portland Planning and Sustainability Commission, says the benefits of the bike parking minimums outweigh the costs. (The commission was slated to discuss details of the proposal Feb. 26.)

"Car parking has a ton of negative externalities: congesting the streets, adding air toxins," Smith says. "Driving is something we're trying to move away from, biking is something we're trying to move toward."

But others are skeptical. "At a time when our city is experiencing a housing emergency," wrote Andrew Hoan, president of the Portland Business Alliance, in a letter to the City Council in October 2018, "this proposal seems to run counter to efforts to make living here more affordable."

Hoan has since softened his stance, citing amendments to the proposal. "Portland is a bike town and needs bike parking," he tells WW. "We also need housing. We will continue to monitor how this new proposed code meets the needs of our community."

City planner Eric Engstrom says it's hard to know whether adding a bike parking requirement would increase housing costs in the central city—though he's confident it would take relatively small tweaks for larger buildings to meet the new standards. "It wouldn't take much to convert a few car parking spots to fit the requirements," Engstrom says.

Early opposition to the plan to increase bike parking has softened as amendments and changes to the proposal were floated to the planning commission. Gwenn Baldwin of Oregon Smart Growth penned a letter late last year to the Bureau of Transportation, proposing that in-unit bike storage count toward meeting the requirements.

"We need to avoid a regulatory structure that pits bikes, housing and retail against each other for the same space," she wrote.

One of the recent amendments submitted to the planning commission partly echoes Baldwin's hopes. It proposes that in-unit bike "nooks" count toward somewhere between 20 and 50 percent of the required bike parking.

The city has set a goal that 25 percent of total commutes in Portland be by bicycle by 2030. Right now, the number hovers between 6 and 7 percent.

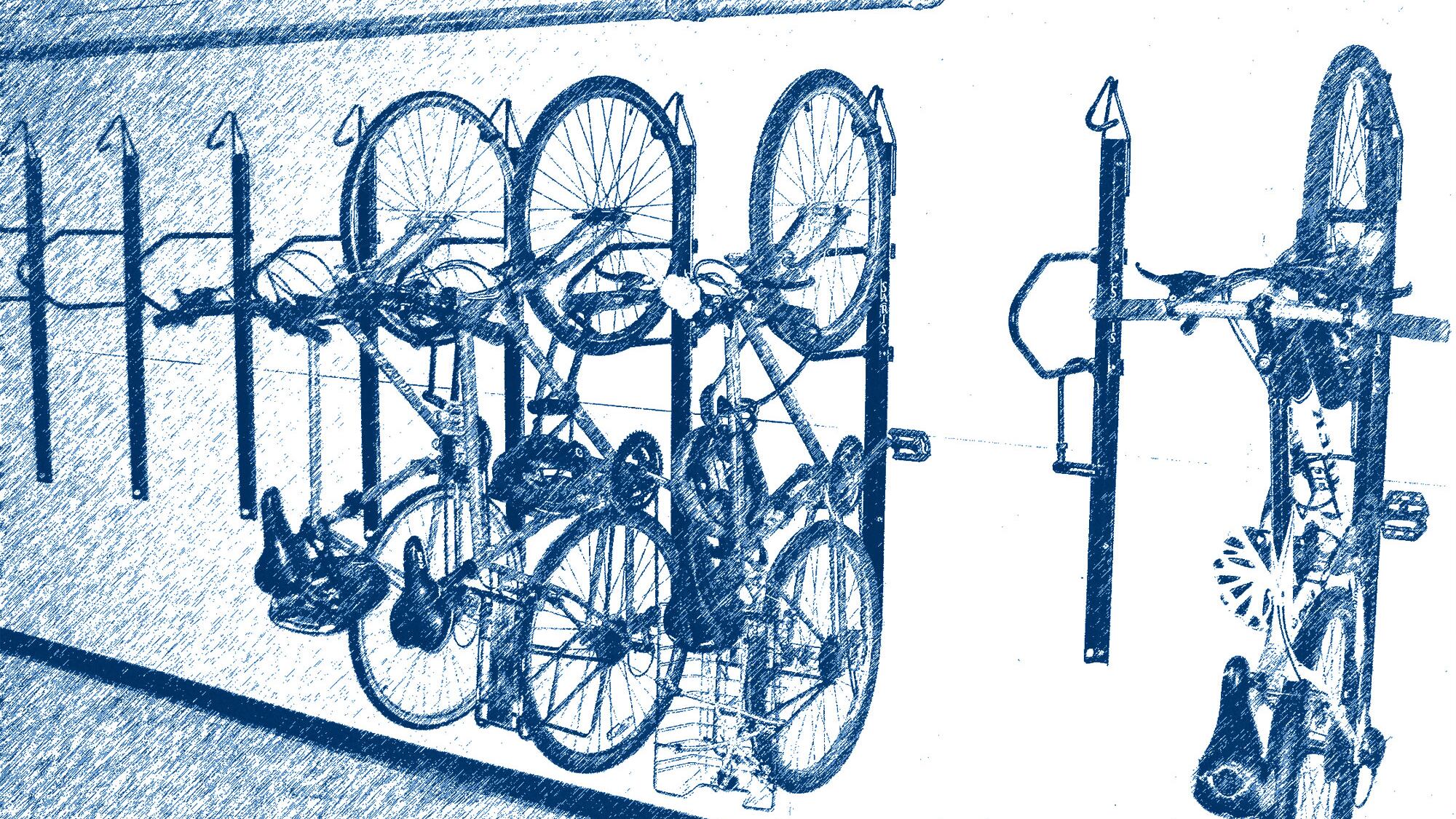

A vision of the future is on display at a new apartment and shopping complex in Northeast Portland, where on a recent wintry day, the city's biggest indoor bike parking lot was about half full.

The Cycle Station in the Lloyd District has 600 bike parking spaces available to shoppers, visitors, and residents of the nearby Hassalo on 8th apartment complex for a monthly fee.

The complex itself has around 225 reserved bike parking spaces for its 657 residents. Combined, that's 1.8 spots for every dwelling unit—20 percent more than the 1.5 bike parking spots per unit currently required by the city in new developments.

Not all of those spaces are in use. (Hassalo's managers could not be reached for comment.) But transportation wonks hope more supply will coax more demand.

Smith says upping the requirement for bike parking would entice the 60 percent of bikers he calls "interested and concerned" riders who don't use their bikes consistently to make biking the method of choice for getting around the central city.

"I'm worried about the line cook in the fast-food restaurant who can't bike to his job because of lack of spaces," Smith says.

Correction: An earlier version of this article stated that Portland City Council would vote in March whether to expand bike parking requirements for developers. The vote will happen this summer.