Address: 7421 N Denver Ave.

Year built: 1916

Square footage: 997

Market value: $1 million

Owner: Farmers Barn LLC

How long it’s been empty: More than 4 years

Why it’s empty: Failed nightlife ambitions, successful squatters

In 2018, the owner of the Farmer’s Barn died, and the neighborhood dive bar on North Lombard Street closed its doors for good.

The building was purchased the following year by a California developer, Tim Brown, for $720,000. In 2021, he roped in his son and a local music promoter to help with the project. Whatever plans they had in mind for what neighbors call a “sleepy, dumpy” bar quickly fell apart. The new owners, unable to sell it, have instead left it to rot.

In the meantime, a new crop of regulars has moved in.

On Saturday, a man was asleep on a couch inside. A hole had been burned through the floor into the cellar. The walls were covered with graffiti, the buildings’ wiring, furniture and appliances had been plundered by thieves.

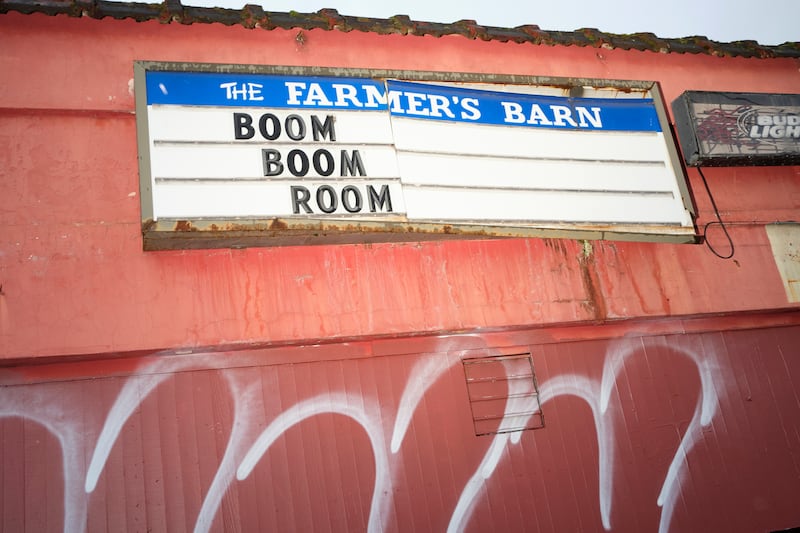

The marquee outside calls it the Boom Boom Room. And the building and surrounding property have become the neighborhood’s most persistent—and, according to neighbors, dangerous—homeless encampment.

Robert Squires, a mail carrier who lives two doors down from the bar, says he’s had a gun pulled on him twice by people in the encampment. “It’s surreal. It’s horrifying,” he says.

For a while, a man had fixed up the dilapidated building as a sort of thrift store for what neighbors say were stolen goods. He ripped open a back wall to create a makeshift garage, where he parked a golf cart. The owners boarded up the back wall, but the front door remains unsecured.

The property is now used as the local dump, and people occasionally drive by and drop off unwanted clothes that pile up in the sidewalk and street.

Over the years, Arbor Lodge neighbors have gone to every city bureau they can think of, asking for help. They’ve called the police. They’ve called the fire bureau. They’ve filed code complaints.

“The fire marshal is the only person who’s ever responded to any of my calls over the years—because there’s billowing smoke coming out from inside,” Squires says.

Meka Webb lives directly next door to the bar, and her home office overlooks the tent-filled alleyway. The near-nightly fires terrify her, particularly when they’re inside the abandoned building.

But calling 911 doesn’t help. In fact, she says, the police told her to stop. “I’m scared to leave my house,” she says.

At some point, the city posted a large red “U” sign on the former tavern’s facade, signifying that the fire marshal has determined the building may be too dangerous for firefighters to enter.

But the city appears to have done little else since, other than notify the building’s owner.

Two complaints filed with the city’s Bureau of Development Services in early 2022 were closed out within a few months.

Eric Marentette sent a series of emails to city officials asking why more wasn’t being done. In May, a city inspector said she’d ordered the owner to board up the bar. Then, in September: “A notice was sent to the owner in late July regarding keeping the site secure, removing trash and other items from the outdoor areas and cutting the grass,” a city administrator in the Property Compliance Division wrote.

City officials, it turns out, aren’t the only ones trying to reach the building’s owners.

Their broker, Jason VanAbrams, tried for much of past year to sell the building, to no avail. The building was marketed as a restaurant, but “the squatters ruined it,” he says.

The listing expired, and VanAbrams hasn’t been in contact with the owners since. “They’re stuck with this derelict piece of property. They can’t do anything with it,” he says.

For the past year, the shell of what was once the Farmer’s Barn was owned by a limited liability corporation created by Brandon Brown, with two members: Tim Brown and Michael Quinn, a music promoter and one of the founders of the Doug Fir Lounge.

The LLC was dissolved in 2021. Neither Brandon nor Quinn responded to WW’s calls.

When reached by phone, Tim Brown told WW he’d been “bought out by my partner” and no longer owned the building.

“You got the wrong person for the comment, but I would suggest you talk to City Hall,” he said.

On Wednesday, Dusty McCord, vice chair of the Arbor Lodge Neighborhood Association, did exactly that.

“The current situation is nothing short of a disaster that has been traumatizing our neighborhood for over a year,” he told leaders at last week’s City Council meeting.

And, this time, the neighbors’ pleas appear to have found a sympathetic ear.

“Don’t go anywhere,” Mayor Ted Wheeler told McCord. “I know we have a lot to say on this subject.”

They did. For nearly 10 minutes, the mayor and city commissioners took turns telling McCord that they were aware of the problem—and doing everything they could to fix it.

That very day, the Bureau of Development Services asked a Multnomah County circuit judge for an administrative warrant. If granted, the city can board up the building and fence it off without the owner’s permission.

The timing was “entirely coincidental,” says Ken Ray, spokesman for the bureau. “The warrant has been in process for a while,” he says, the result of another nuisance complaint that’s been open since July.

Marentette is encouraged, but skeptical. “This is after I’ve literally begged them to escalate this situation for months. They finally did, but that doesn’t guarantee a good result,” he wrote in an email to WW.

Even the trespassers are happy the city is finally doing something about the mess.

“People come through here and just dump shit,” says Rich, a former shipyard worker who is living in a tent in the alleyway. He declined to give his last name but said he’s addicted to meth and has been living on the street for six months.

He burns fires to stay alive. His fingers were frostbitten in the December cold snap. But he doesn’t want to move to a shelter out of fear that his possessions—he owns a bicycle and a generator—would be stolen. “There’s safety in numbers,” he says.

Every week, WW examines one mysteriously vacant property in the city of Portland, explains why it’s empty, and considers what might arrive there next. Send addresses to newstips@wweek.com.

0 of 10